Finest Hour 166

Churchill Proceedings – “Mr. Churchill’s Profession”

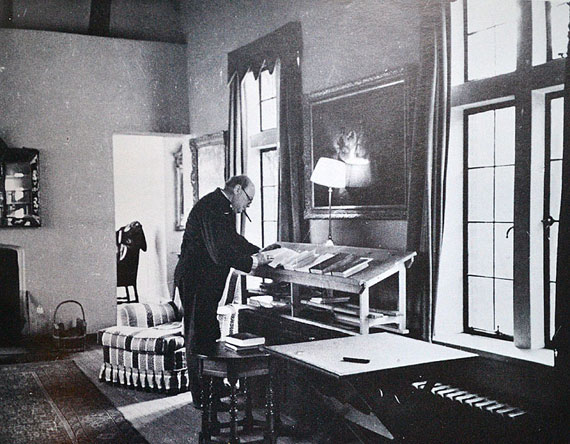

Churchill at his writing desk at Chartwell

July 24, 2015

Finest Hour 166, Winter 2015

Page 36

By Peter Clarke

31st International Churchill Conference, New Orleans, LA, 4 April 2014

Churchill at his writing desk at Chartwell.In exploring the many fascinating and diverse facets of Churchill’s life, let us not ignore the obvious. This man’s vocation was politics. In the end everything else was subservient to that commitment. But let us add some other ingredients.

Churchill at his writing desk at Chartwell.In exploring the many fascinating and diverse facets of Churchill’s life, let us not ignore the obvious. This man’s vocation was politics. In the end everything else was subservient to that commitment. But let us add some other ingredients.

2024 International Churchill Conference

First, Winston Churchill was an aristocrat: the grandson of the seventh Duke of Marlborough whose vast and impressive country house is aptly called a palace. It was Winston’s birthplace; he pined for a country house of his own; eventually he found one in Chartwell, in its wonderful setting in the Kent countryside with its spectacular views over the ancient forest of the Weald. With about sixteen staff on the payroll, it was an enormous expense (though admittedly a bit smaller than Blenheim Palace).

His great ancestor, John Churchill, created first Duke of Marlborough, is described in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, with some understatement, as “politician and army officer.” Likewise the young Winston. Yet, when only twenty-four years old, he took a big career decision: to leave the army. Clearly politics supplied the motive, but it certainly couldn’t supply the means. In those days British MPs were not paid; the salary first implemented in 1911 by the Liberal Government was £400 a year—say £30,000 today or $50,000—a respectable income for a trade-union official elected as Labour MP but not one that could sustain Churchill’s lifestyle. For most of his career in the House of Commons, the annual salary he drew as an MP was less than his annual wine bills.

And the army had simply not been able to fill this financial gap. Even when Churchill became a government minister, this promotion did not solve his financial problem. Before World War I the standard cabinet minister’s salary of £5000 would be worth £400,000 in today’s money (say $700,000); but the pound was worth less after the war, while the salary stayed the same—worth between £150,000 and £250,000 today (say $300,000-$400,000). This was not enough for the owner of Chartwell—at once his palace and his prison, where he worked into the small hours, dictating his books and journalism, dependent on his literary earnings to keep afloat.

Of course, for Churchill there was never a clean break between fighting and writing. His first contract in 1897 was for a series of dispatches as a war correspondent from Afghanistan, followed by his reporting on Kitchener’s campaign in Egypt and the Sudan. Two books were quickly made out of these dispatches, The Malakand Field Force and The River War. Two further volumes drew on his role as war correspondent in the South African War—London to Ladysmith and Ian Hamilton’s March. From this time onward, the author took to quoting Dr Johnson: “No man but a blockhead ever wrote except for money.”

At the start of World War I Churchill was a cabinet minister, responsible for the Royal Navy; he became, briefly, a serving officer on the Western front; and then a cabinet minister again with widely various responsibilities. This personal experience of waging war was rehearsed in the volumes of The World Crisis (1923-29—to which he later added a volume on the Eastern Front. It was this multi-volume work that reanimated his career as a writer. He began it while still a cabinet minister under Lloyd George in 1919-20; he was to finish it as a cabinet minister under Stanley Baldwin in 1925-29. The contract he signed was for £27,000—perhaps £750,000 today (or a million and a quarter dollars).

Here was the template for Churchill’s last major work as an author, The Second World War, in the six volumes published worldwide from 1948 onward. Churchill was now the most famous man in the world, the author of victory, and, not least, a writer who had a shrewd idea on how to cash in on his celebrity status. David Reynolds’ fine book, In Command of History, estimates Churchill’s proceeds, in twenty-first century terms, at about £17 million (say $25 million). In 1945, as he contemplated this last great literary task, Churchill told one editor: “After all, I am a member of your profession. I’ve never had any money except what my pen has brought me.”

It is this sheer professionalism that we should not forget when we are tempted to speak of his many other activities. Churchill, of course, had many talents, for example as an artist. But look at the way that he himself wrote about this in his essay, significantly titled “Painting as a Pastime.” He says that at a low point in his career—the middle of World War One, when he suddenly lost his cabinet post—“the Muse of Painting came to my rescue…and said: ‘Are these toys any good to you? They amuse some people.’” Churchill never talked about his vocation in politics in such terms, nor about his profession as a writer. In his agreeable hobby of painting, by contrast, he recommends Audacity as the watchword for self-proclaimed amateurs like himself: “We may content ourselves with a joy ride in a paint-box.”

But writing was no joyride—not a hobby, like his painting. Nor was it just a part-time job but one that, by most ordinary tests, became his primary occupation and his primary source of income. In the 1930s his earnings from writing were thirty times higher than his income from politics. Ask any accountant: what was this man’s profession?

And the second reason to take Churchill seriously as an author is that he was accepted by other professionals on these terms. In 1934 Rudyard Kipling wrote a letter to Churchill, admiring the second volume of his biography of the great Duke of Marlborough: “I very much like the clarity of the history and, as craftsman to craftsman, the workmanship—notably in the ‘Structure of the War’, and in certain purple patches which you have sparingly but very wisely used.” There could surely have been no greater compliment, from a writer who self-consciously talked as a fellow craftsman. Thus Churchill was a professional author in this double sense: not only relying upon the proceeds for the bulk of his income but also acquiring the necessary skills and upholding professional standards in his work.

Churchill was the author of three major literary works that are hardly the staple of a professional politician. First there is the biography of his father Lord Randolph Churchill, published in two volumes in 1906, for which Winston got an amazing advance of £8000—say a million dollars in today’s money. This powerfully encouraged his taste for literature and for more big advances in future. Secondly, in 1929, when he was still Chancellor of the Exchequer and expecting to stay in the cabinet for another five years, Churchill gaily signed a contract for a big biography of his ancestor, the first Duke of Marlborough. He thought he could dictate it in his spare time as a cabinet minister.

When the biography was finally published in the 1930s it ran to a million words and his loyal publishers were appalled. Harraps in London brought it out in four fat volumes; Scribners in New York did it in six—a bad marketing decision. But it was a work that met serious literary and scholarly standards as well as netting a professional income for its author.

Thirdly, we have to understand how Churchill undertook what proved to be his final great publication: his History of the English-Speaking Peoples, published in four volumes in 1956-8. This has often been rather disparaged, especially among historians, as an old man’s book. Moreover, especially since David Reynolds showed us how Churchill constructed the volumes of his Second World War, relying heavily on a bevy of ghostwriters, it has often been assumed that the History was put together in a similar way, once Churchill had retired.

Not so. Most of the book was already drafted by the end of 1939—and composed by Churchill himself (admittedly with research assistance). The first three volumes as published in the 1950s are basically what Churchill drafted in 1938-9; only the last volume is the work of other hands—and even here the long section on the American Civil War had been dictated by Churchill in 1939. This was the project that had occupied his time and his mind on the eve of World War II.

Of course the theme was to be influentially developed in the postwar period in Churchill’s speech at Fulton, Missouri, in March 1946. This was when he first talked of a “special relationship” between the United States and Great Britain—“the fraternal association of the English-speaking peoples.” Churchill’s concept of the English-speaking peoples thus has a resonance beyond the writing of two thousand years of history. It has also informed the making of history throughout the second half of the twentieth century.

The tension between writing history and making history is surely relevant to our broad theme of fighting and writing. Thus we can make a distinction between what I will call “fighting as writing”, as opposed to “writing as fighting”, and categorise Churchill’s books on that basis.

Under the first head, “fighting as writing”, we can include all the books that he retrospectively made out of his own experience of war—the four early books as a war correspondent; the five or six volumes on World War I; the six volumes on World War II. All of them purport to give an objective account of the wars in which Churchill was involved, and succeed in a remarkably readable way. But each is infused with his own experience; and the accounts of the two world wars are inevitably from the perspective of Churchill, looking back as a participant with a case to make. He admitted as much himself.

Under the second head, “writing as fighting”, we can see the significance of his profession as a writer, in equipping him with a literary arsenal: enabling him to deploy the weapons of rhetoric as a war leader. As Churchill said himself, when he assumed power in 1940, “I felt as if I were walking with destiny, and that all my past life had been but a preparation for this hour and for this trial.” Now these well-known words reflect a view of his political career. But perhaps his other career—as a writer—had also prepared him. For when we read Churchill’s great oratory of the wartime years, we are reading the words of an author who had just finished his own draft of his History of the English -Speaking Peoples.

Churchill did not fail the rhetorical challenge that faced him in 1940, when he rallied his own countrymen in a uniquely effective exercise in the politics of emotion. Moreover, he made a significant impression on public opinion across the Atlantic, which helped change perceptions of the British cause, Empire and all, which was an ideological precondition of Lend-Lease. And the later close alliance between the US and Britain built on such foundations. Little wonder that the themes in the great war speeches, when read today, often seem familiar. Little wonder that the appeals to the common history and common destiny of the English speaking peoples, in girding themselves to defy tyranny, seem familiar sentiments—especially to readers of his History of the English-Speaking Peoples.

In the war years, however, this had not yet been published. At the time, those who marveled at the sonorous ring of the great orator’s phrases could not have known that these had already been well honed by Churchill the writer. He himself knew well enough. As he said at the time of his eightieth birthday: “if I found the right words you must remember that I have always earned my living by my pen and by my tongue.”

Peter Clarke is a British author and historian, whose publications include The Last Thousand Days of the British Empire and A Question of Leadership: From Gladstone to Thatcher. He is a former Master of Trinity Hall, Cambridge.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.