Finest Hour 69

Churchill: A Study in Oratory

Winston Churchill, Parliament Square, London © Sue Lowry & Magellan PR

June 17, 2016

Seven Lessons in Speechmaking From One of the Greatest Orators of All Time

By Thomas Montalbo, DTM

Finest Hour 69

He wasn’t a natural orator, not at all. His voice was raspy. A stammer and a lisp often marred many of his speeches. Nor was his appearance attractive. A snub nose and a jutting lower lip made him look like a bulldog. Short and fat, he was also stoop-shouldered.

Yet this man—Sir Winston Churchill—became probably the greatest orator of our time and won the Nobel Prize for his writings and “brilliant oratory.” How did he do it? And what lessons can all Toastmasters learn from him to help them make better speeches?

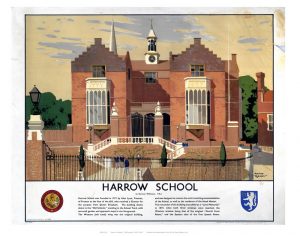

In school, Winston Churchill was a backward student. But he wasn’t stupid. He later explained, “Where my reason, imagination or interest were not engaged, I would not or I could not learn.” But the English language fascinated him. He was the best in his class.

Macaulay and Gibbon, two of England’s most famous historians, dazzled him with their styles of writing. The impact these authors made on his mind stayed with him for life, as his speeches show. Because their styles were markedly different and yet both charmed him, he believed this showed, as he put it, “What a fine language English is. . .”

His English teacher once said, “I do not believe that I have ever seen in a boy of 14 such a veneration for the English language.” Churchill called the English sentence “a noble thing” and said, “The only thing I would whip boys for is not knowing English. I would whip them hard for that.” Lord Moran, his physician and intimate friend, wrote:

“Without that feeling for words, he would have made little enough in life. . .”

Lesson #1

Know, respect and love the English language.

An Avid Listener.

The greatest influence in his early life was his father, the leader of the House of Commons. Young Winston often visited Parliament and heard all the speeches. Sitting, watching and listening, he absorbed the oratory as if by osmosis. Devotedly, he read and reread his father’s speeches, many of which he knew by heart. He also read and studied the speeches of Oliver Cromwell, William Pitt, William Gladstone and many others.

At age 21, Churchill came to the United States and met Bourke Cockran, a New York Congressman whom he described as “a remarkable man. . .with an enormous head, gleaming eyes and flexible countenance.” But most of all, Churchill admired Cockran for the way he spoke.

The Congressman had a thundering voice and often spoke in heroic and rolling phrases. When Churchill asked his advice on how he could learn to spellbind an audience of thousands, Cockran told him to speak as if he were an organ, use strong words and enunciate clearly in wave-like rhythm. They corresponded for many years.

Adlai Stevenson, himself a notable speaker, often reminisced about his last meeting with Churchill. “I asked him on whom or what he had based his oratorical style. Churchill replied, ‘It was an American statesman who inspired me and taught me how to use every note of the human voice like an organ.’ Winston then to my amazement started to quote long excerpts from Burke Cockran’s speeches of 60 years before. ‘He was my model,’ Churchill said. ‘I learned from him how to hold thousands in thrall.’”

Lesson #2

See and hear good speakers in action, and study the texts of their speeches.

Stimulated by his father’s career, young Churchill’s ambition was to go into politics, but he worried about his speech impediment. So he consulted a throat specialist. The doctor found no organic defect and told young Churchill only practice and perseverance would help him.

Diligently and faithfully, he practiced and persevered. He believed people should never submit to failure. Years later he said in a speech, “Never give in! Never give in! Never give in except to convictions of honour and good sense.”

He rehearsed aloud to make sure he wouldn’t muff words or stumble over them, particularly words starting with “s.” While walking on the street he repeated such sentences as, “The Spanish ships I cannot see since they are not in sight.” Eagerly he sought opportunities to speak. All this helped him to lose the inhibition that had caused his stammering, though he never totally lost his lisp.

An Attention-Getter

But even this turned into an advantage. Randolph Churchill once theorized that his father may have exploited the residual impediment to advantage to achieve an individual style of oratory. When Winston was 23 he wrote an unpublished article on oratory, The Scaffolding of Rhetoric. Describing the physical attributes of the orators, he wrote, “Sometimes a slight and not unpleasing stammer or impediment has been of some assistance in securing the attention of the audience. . .”

Lesson #3

Endure your handicaps if they can’t be cured and turn them to your advantage. Never give in!

Failure in academic schooling, except for English, led young Churchill to a military academy. Enthusiastic about his military studies, he was highly successful at the academy. After graduating he took a commission as lieutenant in a cavalry regiment and began his army career.

Routine army life in India gave him free time between drills and polo. Deciding to make up for his lack of a university education, he spent his leisure hours reading. He asked his mother to send him certain books from England—by the box. For four to five hours each day he read more of Macaulay and Gibbon, as well as Shakespeare, Plato, Aristotle, Burke, Darwin, Maithus and Bartlett’s Quotations.

He approached these books, as he once said, “with a hungry, empty mind, and with fairly strong jaws, and what I got I bit.” This reading gave him knowledge and opportunities for independent thinking. Nourished in the fertile soil of such excellent reading, ideas developed in his enriched mind. His interests widened and matured.

Lesson #4

Read good books to broaden your mind and stimulate your thinking, since effective speaking depends on both knowledge and thought.

The Power of Kings

Although Churchill never submitted his article on oratory, The Scaffolding of Rhetoric, for publication, the manuscript survived and was printed two years after his death—some 70 years after be had written it. He begins the article by claiming that oratory gives a man the power of a great king, but “before the orator can inspire audiences with any emotion he must be swayed by it himself. When he would rouse their indignation his heart is filled with anger.

Before he can move their tears his own must flow. To convince them he must himself believe. . .

He goes on to examine in detail “certain features common to all the finest speeches in the English language.” He identifies them as follows: correct diction, rhythm, accumulation of argument, analogy and extravagance of language. Here’s a summary:

- Correct Diction.”Knowledge of a language is measured by the nice and exact appreciation of words.” Use “the best possible word . . . short, homely words . . . so long as such words can fully express the speaker’s thoughts and feelings.”

- Rhythm. Sound has a tremendous effect on an audience. Create a rhythmic flow of sounds with long, rolling, sonorous sentences and balanced phrases.

- Accumulation of Argument. Set forth a series of facts, all pointing in one direction, piling argument on argument, leading the audience convincingly to the climax “by a rapid succession of waves of sound and vivid pictures.”

- Analogy. “Apt analogies are among the most formidable weapons of the rhetorician.” Bring ideas down to earth for the listeners in terms of their everyday knowledge. Comparison clarifies understanding. Churchill gives several examples from other speakers. Here’s one from his father “Our rule in India is, as it were, a sheet of oil spread over and keeping free from storms a vast and profound ocean of humanity.”

- Extravagance of Language. This is needed to arouse the emotions of both the speaker and the audience. “Some expression must be found that will represent all they are feeling.” He gives a couple of examples, including William Jennings Bryan’s declamation that electrified a national political convention: “You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns, you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.”

A Self-Portrait

When Churchill wrote his article on oratory, he also had begun work on his first book, a novel entitled Savrola, published three years later. He worked much of the article into the novel and added such techniques as timing, alliteration, repetition and voice modulation. Although fiction, the novel’s central character, Savrola, is actually the author’s self-portrait. Many things about Savrola—his talents, thinking, books, methods of preparing and delivering speeches—axe exactly like Churchill’s.

Here is an excerpt from Savrola on how the hero prepares a speech:

On the delivery of the hero’s speeches:

‘Scene. . . a gigantic meeting house . . . nearly 7,000 people . . . Though he spoke very quietly and slowly, his words reached the furthest ends of the hall. His voice was even and not loud, but his words conveyed an impression of dauntless resolution . . . here and there in his sentences he paused as if searching for a word. His passions, his emotions, his very soul appeared to be communicated. He raised his voice, and in a resonant, powerful, penetrating tone…began the peroration….’

The Scaffolding of Rhetoric and Savrola thus describe Churchill’s theory and practice of oratory which he pursued consistently during half a century of speechmaking.

Lesson #5

Use rhetorical devices to help your listeners understand and remember what you say, and to stir their feelings.

While in the army Churchill maintained his keen interest in politics and read newspapers avidly to keep abreast of public affairs. After five years, he resigned his commission to enter politics. At 26, he was elected to Parliament.

From his first speech to his last, he always depended on thorough preparation. He worked as hard in his seventies to prepare a speech as he did in his twenties. To him a speech, both in Substance and Form, had to be a Work of Art. As such, it demanded much time and effort. “I take the very greatest pains with the style and composition,” he once said. “I do not compose quickly. Everything is worked out by hard labour and frequent polishing. I intend to polish till it glitters. . .”

So his eloquence as an orator didn’t come easy. Only by the sweat of his brow did he achieve brilliance. In the beginning he wrote out his speeches in longhand. Later, he dictated every word to a secretary, who took it in shorthand or on the typewriter. Spending entire days dictating, he paced up and down the room, puffing at a cigar. He put his ideas to rhetoric as composers set theirs to music. The cigar in his hand served as a baton to punctuate the rhythm of his words. He tested words and phrases; muttering to himself; weighing them; striving to balance his thoughts; making sure the sound, rhythm and harmony were to his liking. Then he came out loudly with his choice and his secretary took it all down. At times he said, “Scrub that and start again” or “Gimme!” as he snatched the paper from the typewriter to scan a phrase.

Finally, he sat down at his desk and revised the triple-spaced typewritten draft. While often impatient and inconsiderate of other people, he was neither with words. Final alterations, substitutions, insertions, deletions—he applied them all like the finishing touches to a painting.

Next came rehearsals of his written speeches. He practiced by reciting them aloud. As he boomed away in his room, his words could be heard along with crashing knocks on the furniture. No opportunity to rehearse was overlooked, even while taking a bath. As he got into the tub he would start murmuring. Story has it that the first time this happened his valet asked, “Were you speaking to me, sir?” “No,” came the reply, “I was addressing the House of Commons.” At private showings of films in his house he enjoyed the movie and at the same time rehearsed his speech in a low rumble with gestures. As a result of such diligent rehearsing, when he gave his speeches his delivery was so natural it seemed effortless.

Lesson #6

Put forth your best efforts to prepare your speeches and seize every possible opportunity to practice them.

Some 2,500 of Churchill’s speeches were published in book form seventeen years ago. A critical review at the time of publication stated, “The speeches, of course, are pure gold interlarded now and then with just the least bit of dross.

The biggest nuggets—the ‘Finest Hour,’ for example—arc beyond price.” Edward Heath, a former leader of Britain’s Conservative Party, also commented on the speeches, saying that “Churchill’s words will live on when the statues erected in his memory have crumbled.”

Nevertheless, Churchill’s written words alone can’t do what he did when he spoke them. Aneurin Bevan, the British socialist leader, said, “Nobody could have listened and not been moved….” Churchill’s speeches, even if delivered verbatim by someone else, couldn’t have had the same effect on audiences.

Always resolutely assured, Churchill felt with his whole being that he knew what he was talking about. He put the stamp of his personality on all his speeches, delivering them in his own distinct style.

“What kind of people do they think we are?” he asked of the enemy. The incisive, intense, affronted tone of his voice as he said those words told eloquently of his anger, disgust and determination to fight on. Didn’t the enemy realize the English were a people who would never cease to persevere—who would rather see their country a shambles than give in to the enemy? He transmitted that determination to his people through one stirring speech after another until they all caught his spirit.

Churchill’s loathing for the enemy, especially Adolf Hitler, had him almost foaming at the mouth. He drove a truckload of sarcasm and scorn into his description of Hitler as “this bloodthirsty guttersnipe . . . a monster of wickedness, insatiable in his lust for blood and plunder. . . “or whenever he rolled the word “Nazi” slowly off his tongue as “Nahhzzee.” To ridicule the enemy and show his utter contempt, he made his words sound as corrupt and shameless as he could.

An important feature of the Churchillian style of delivery was the dramatic pause. He was a master at this. He said once, “I. . . made a pause to allow the House to take it in. . . As this soaked in, there was something like a gasp.” He relied on timing to assure heightened effect because it made silence even more eloquent than words and allowed his listeners to digest what they heard and get ready for what would be said next. His timing—his use of the dramatic pause—forced any restless members of his audience to look at him and listen. Even his “gar-rumphs” and throat clearings came at the right moments.

Snarls and Scowls

Those who saw him say that his facial expressions as he worked through and up to his main points were something to see. He snarled and scowled as he spoke of “strangling the U-boats” or of “the deadly, drilled, docile, brutish masses of the Hun soldiery plodding on like a swarm of crawling locusts” and of “Mussolini, this whipped jackal frisking up by the side of the German tiger with yelps His manner was stern yet stimulating as he growled, “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat.”

Even in his most serious speeches he sprinkled jokes, quips and other humor. While German bombers were devastating London he quipped, “At the present rate it would take them about ten years to burn down one-half of London’s buildings. After that, of course, progress would be much slower.” In one speech he said, “We are expecting the coming invasion; so are the fishes.” In another, “We have a higher standard of living than ever before. We are eating more.” Then, gazing at his ample round belly, and with his eyes twinkling, he added, “And that is very important.”

A Powerful Delivery

Although his voice wasn’t especially appealing, it carried conviction and his delivery gave the impression of power and sincerity. He combined flashy oratory with sudden shifts into intimate, conversational speaking. Each change of pace, each dramatic pause, each rhetorical flourish—all were carefully orchestrated. He roared like a lion and cooed like a dove with hand and facial gestures to suit.

Effective delivery, however, is more than voice and gestures. It is the impact of personality on the listeners. Although Churchill was always carefully prepared, his delivery never lacked spontaneity. He put feeling into his words. He made them breathe with life through his exhilarating and forceful personality. This uniqueness as a person made the difference in his speech delivery, and in his effect on the audience.

Lesson #7:

Let your feelings and personality show in your speeches.

All his life Winston Churchill aspired to the highest glory. That’s why, in spite of or because of natural handicaps, he took infinite pains to develop himself into one of history’s greatest orators. Even if you don’t have his lofty aspirations, these seven lessons from his life can help you make better speeches.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.