Bulletin #143 – May 2020

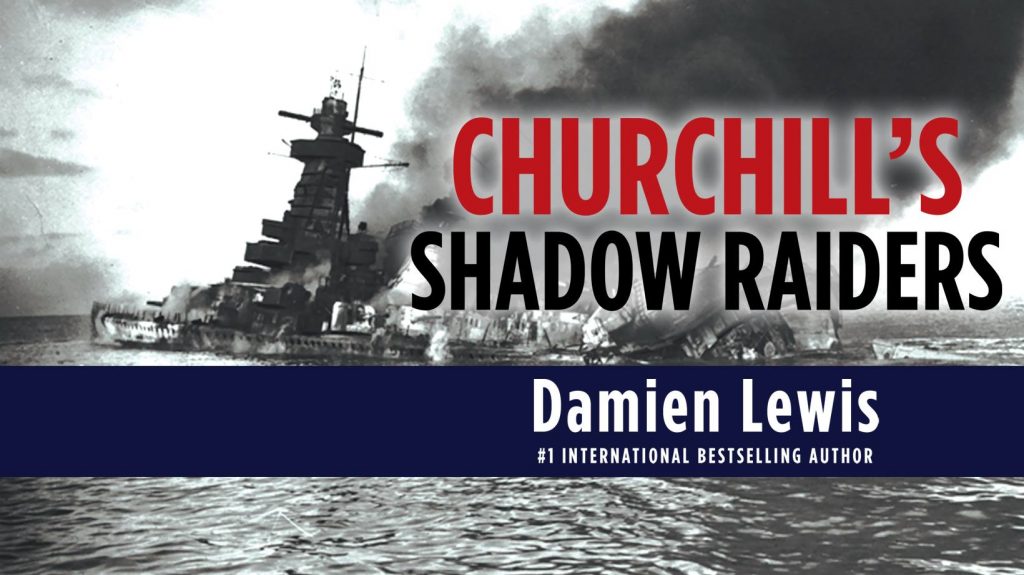

Churchill’s Shadow Raiders: How Theft, Trickery and Deception Secured Victory in WWII

April 27, 2020

By Damien Lewis

In our darkest hour during World War Two, as British pilots came under devastating assault from Nazi Germany’s Luftwaffe, a small chink of hope was delivered by a young and pioneering scientist who masterminded an audacious operation to capture a piece of prized German technology. The resulting discoveries would transform Britain’s strategic approach to the war, but to reap the maximum benefits required a new way of thinking, one to which the military-scientific establishment were fiercely opposed. Wedded to the tried and trusted methods of the past, they were suddenly asked to embrace something altogether unfamiliar and unorthodox – the dark arts of subterfuge. Championing this new and unprecedented field of warfare was none other than Britain’s Prime Minister, Winston Churchill.

Churchill was a rare thing in a politician: a passionate science enthusiast who also had an immense fascination with science-fiction, and was willing to think the unthinkable. Just six weeks after Britain declared war on Nazi Germany, and with Europe on the brink of a catastrophic conflict, Churchill found time to muse about the existence of alien life. In between the two wars, he had written many scientific articles and also invented a variety of sophisticated battlefield devices. But it was the 1917 ‘Haversack ruse’, deployed during the First World War, that would first pique Churchill’s fascination with deception and subterfuge. In it, foremost British military commander and espionage officer, Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, deliberately left a backpack stuffed full of battle plans where he knew the enemy would find it. When they did, and took the documents to be genuine, it resulted in Meinertzhagen’s forces securing a famous victory. Years later, the lessons of the Haversack Ruse would lead to Churchill throwing his weight behind the formation of a top-secret unit dedicated to the craft of subterfuge in WWII.

2025 International Churchill Conference

The London Controlling Section (LCS), aka ‘the Dirty Tricks Committee’, was a curious organization, one devoted entirely to military deception. Inspired by the success of maverick commander Lieutenant-Colonel Dudley Clarke’s pioneering work in the field, LCS was founded in 1941, at a time when the winds of war blew ill for Britain and new ways of fighting were called for, ones based upon cunning and trickery. At its helm were a truly bizarre mixture of socialites and the aristocratic elite, who wielded immense power across all government departments in London and across what was then the British empire. LCS drew its member from a very broach church indeed – including Colonel John Henry Bevan, a prominent stockbroker and one of the financial power-brokers of London, but who was also a serving intelligence officer; Major Ronald Evelyn Leslie Wingate, a British colonial administrator and cousin to Lawrence of Arabia; and Denis Wheatley, the prolific author of thriller and occult novels.

From the outset, Colonel Bevan, known as the ‘Controller of Deception,’ was taken into Churchill’s confidences, resulting in their meeting two or three times a week to conjure up plots of trickery to lay at the enemy’s door. In time, Bevan would set up four special committees, each charged with mastering a different means to mislead and confound the enemy. One, entitled ‘the Racket Committee,’ was chaired by author Wheatley, who was tasked to devise new ruses and novel methods of handing misinformation to the enemy. The LCS would go on to play a pivotal role in orchestrating the trickery of Operation Mincemeat, when a dead body with a briefcase of fake documents was dumped at sea, where it would be found by the enemy, so selling to them a bundle of false intelligence and plans. But its ultimate achievement was to be the masterful deceptions prior to the D-Day landings.

Another top-secret war department, also veiled in secrecy and intrinsically linked to the LCS, was to play a vital role in Allied victory on the D-Day beaches. At the Danesfield Central Interpretation Unit, at RAF Medmenham, in southern England, highly trained photographic interpreters pored over hundreds of images captured by daring pilots on reconnaissance flights over enemy-occupied Europe. Some 80% of all intelligence in WWII would be gleaned from such images: this was war-wining craft beyond compare. One set of remarkable photos fascinated a young scientist-spy, called Reginald Victor Jones. Attached to Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), Jones had already won the admiration of Churchill for his brilliant and intuitive insights about the enemy’s technological advancements. Convinced of the existence of German radar, Jones’ seized on the newly-acquired photos as definitive proof. For the first time, the enemy’s radar system codenamed FREYA had been captured in all its glory on film. But it was to be later photos captured by Flight Officer Anthony ‘Tony’ Hill that truly excited Jones. For some time, he’d been convinced there was a second German radar in operation, a compact and mobile ‘paraboloid’ dish that tracked and targeted Allied warplanes, with devastating results.

In November 1941, a mysterious black speck perched atop a cliff at Bruneval, in northern France, attracted the curiosity of genius photo interpreter, Claude Wavell. Could this be the elusive paraboloid device that Jones and others feared existed? There was only one way to find out: another dangerous reconnaissance flight had to be undertaken, but this one at low level, to capture the ‘dot’ in close-up detail. Hill’s audacious dash over the French clifftops ended in the capture of what would become some of the most acclaimed reconnaissance photographs of the war. There, in clear detail, was the mysterious paraboloid – what the Germans had codenamed the ‘Würzburg’.

By this time, the losses inflicted on Allied bomber squadrons flying over Nazi-occupied Europe had reached devastating proportions, with some 8,000-aircrew killed. Jones had no doubt that the Wurzburg radar was somehow instrumental in those deaths. If he and his team of boffins could somehow examine the installation up close, they might well be able to find a way of ‘jamming’ the device – blinding its signal. But that would require someone to steal the Würzburg and bring it back to Britain. Via Professor Lindemann, Churchill’s close scientific advisor, Jones raised the idea of the daring radar theft with Churchill. While the Prime Minister ‘was all for it,’ Jones’ plan was not well received by a sceptical War Cabinet. But with Churchill’s blessing the wheels begun to turn. Inculcating a can-do spirit, one of the most audacious raids was given the go-ahead.

On the 27 February 1942, that daring snatch mission, codenamed Operation Biting, took place. The successful capture of the Würzburg delighted the military and the scientific community and imbued the British people with a new-found confidence. In his Secret Intelligence Service laboratories, Jones, together with his boffin-colleagues at the Telecommunications Research Establishment (TRE) – Britain’s radar research centre – raced to find a way of defeating the purloined Wurzburg. But as all quickly realised, because it was tuneable over such a large range of frequencies, no traditional method would ‘jam’ it. However, it might be possible to ‘blind’ the Würzburg with a ground-breaking, yet stunningly simple technology, one that Churchill himself had ironically first mooted, back in 1937, when he’d proposed ‘to scatter from the air packets of tin-foil strips’. The resulting host of false radar echoes should ‘simulate a bomber on the enemy’s radar screens,’ so hiding any Allied aircraft on route to their targets amongst the mass of radar ‘chatter’.

The proposal was taken up in earnest by a female scientist, Joan Curran, working at TRE. In her pioneering research she refined the length, breadth and consistency of the metal strips, to produce the perfect radar echo on the Wurzburg screen, resulting in a device codenamed ‘WINDOW’. As Allied bomber losses continued to rise sharply, Jones and the TRE scientists argued that the time was ripe to utilize WINDOW, and save ‘hundreds of aircraft and thousands of lives’. But those in charge argued that by doing so the secret of WINDOW would be discovered and duly copied by the enemy, resulting in the blinding of our own crucial radar systems. Britain’s leading radar scientist, Robert Watson-Watt, known as ‘the father of radar,’ warned that deploying WiNDOW risked destroying Britain’s air defences, leaving the nation open to attack. Despite persistent lobbying by Jones and the TRE scientists, the cynics managed to argue for delay.

But by the summer of 1943, the naysayers had been over-ruled. At dusk on 24 July 1943, 779 British heavy bombers headed for the German city of Hamburg, releasing clouds of tinfoil strips as they flew. Hamburg was then the most heavily-defended city in the world, but the release of WINDOW during ‘Operation Gomorrah’ wreaked sheer havoc on the city’s radar defences. The following morning, Hitler awoke to the devastating news that Hamburg’s critical shipyards, armament factories, U-boat pens and oil refineries had been heavily bombed.

Of course, the extraordinary potential of WINDOW had not been lost on Colonel John Henry Bevan, the stockbroker-spy in charge of the London Controlling Section. If WINDOW could mimic flights of bombers thundering through the skies, what else might it be capable of replicating? With D-Day in the offing, could WINDOW somehow be used to create ghost fleets where none in truth existed, so convincing the enemy that the Allied landings were to take place in an entirely different location from where they would go ashore, on the Normandy beaches? A few weeks before Christmas 1943, Bevan and his colleagues at the LCS began to turn their brilliant minds to preparing for the biggest and most sophisticated deception plan ever devised, codenamed BODYGUARD. The location and timing of the D-Day landings was the most closely-guarded Allied secret of the war, and as Churchill most elegantly stated: ‘Truth deserves a bodyguard of lies.’ Rising to this challenge, Bevan and his team at LCS began to mastermind a series of elaborate ruses designed to deflect attention away from the D-Day landings. This would end up being the greatest single deception operation ever launched by humankind.

In two utterly ingenious military deceptions, codenamed Operations Taxable and Glimmer, the technology that had been devised by RV Jones, Curran and others was adapted and refined to create a vast ghost convoy of battleships, cruisers and destroyers steaming across the British Channel, where in truth none existed. The same was done regarding fleets of warplanes filling the skies, which were in truth clouds of tinfoil strips drifting in the June air. The illusion of two separate invasion forces steaming hell-for-leather for the Pas de Calais and the Seine Peninsula, succeeded in confusing Hitler and his senior military commanders masterfully. Meanwhile, the real invasion – the largest seaborne assault in history – raced in towards the Normandy beaches and on to triumph.

You can find an excerpt of Churchill’s Shadow Raiders here.

Damien Lewis is an award-winning historian, war reporter, and bestselling author. He spent over two decades reporting from war, disaster, and conflict zones around the world, winning numerous awards. He has written more than a dozen books about WWII, including The Ministry for Ungentlemanly Warfare, The Dog Who Could Fly, SAS Ghost Patrol, and The Nazi Hunters. His work has been published in over forty languages, and many of his books have been made, or are being developed as feature films, TV series, or as plays for the stage.

Damien Lewis is an award-winning historian, war reporter, and bestselling author. He spent over two decades reporting from war, disaster, and conflict zones around the world, winning numerous awards. He has written more than a dozen books about WWII, including The Ministry for Ungentlemanly Warfare, The Dog Who Could Fly, SAS Ghost Patrol, and The Nazi Hunters. His work has been published in over forty languages, and many of his books have been made, or are being developed as feature films, TV series, or as plays for the stage.

This article by Damien Lewis on Churchill’s Shadow Raiders has been sponsored by Kensington Publishing Corp., New York, NY. Photo Credit: Andrew Millard

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.