Bulletin #207 — Aug 2025

Money, Money, Money

August 6, 2025

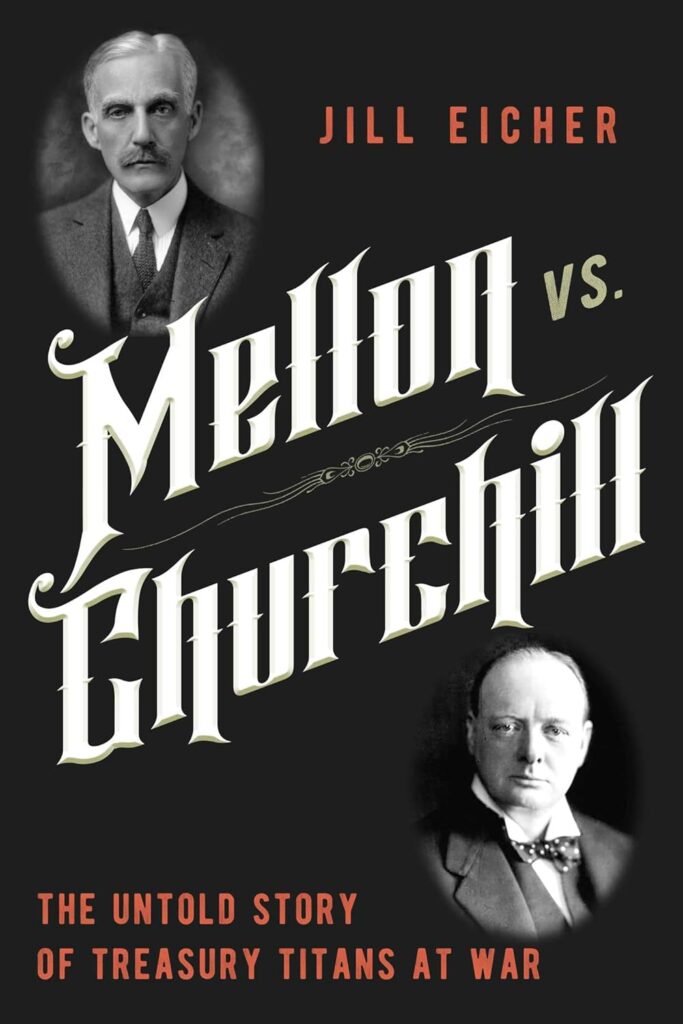

Jill Eicher, Mellon vs. Churchill: The Untold Story of Treasury Titans at War, Pegasus, 2025, 368 pages, $32. ISBN 978–1639366422

Review by Ted R. Bromund

Testifying to the fascination and greatness of Winston Churchill’s life is that there appears to be no end to the compelling stories that can be told about him. A decade ago, David Lough opened a rich new vein with his superb No More Champagne, the tale of Churchill’s epic and often precarious personal finances.

Now Jill Eicher continues the financial theme with a similarly epic saga, this time set on the international level, of Churchill’s efforts as Chancellor of the Exchequer to extinguish Britain’s Great War debts to the United States—and of Andrew Mellon’s struggle as U.S. Treasury Secretary to arrive at the impossible solution that satisfied Congress, Britain and all the U.S.’s other debtors, and common sense alike.

As Eicher reminds, us, the 1920s remain the under-examined decade of Churchill’s life. His superb My Early Life ensures that his adventures before he entered government will always be appreciated, his World Crisis does the same for the Great War, and his resistance to appeasement and his apotheosis in 1940 remain his crowning glory. But perhaps because his early interwar years lacked a compelling theme, Churchill never wrote the story of his life and the wider times in the 1920s, when he travelled hesitantly from the Liberals back to the Conservatives.

2025 International Churchill Conference

If those years had a theme for Britain, it was the need to adapt to diminished expectations and resources. When in office as Chancellor from 1924 to 1929, Churchill approached this task with typical zest and conviction, but it was not one that he found naturally congenial. The blunt fact was that, if it had not been for the financial and industrial might of the United States, the Allies would have been defeated by Germany—and part of the price of bringing Uncle Sam into uneasy association with the Allies was that U.S. assistance came in the form of loans that both Congress and much of the American public expected to be repaid with interest.

This was both understandable and, as Churchill repeatedly explained, unwise. Leaving aside the moral point that Britain and France had paid for victory in blood while the U.S. had paid mainly in dollars, the blunt fact was that—unlike normal commercial loans—the Allied debts to the United States had been shot away in shell, not expended in productive enterprise that could be used to repay American lenders. When coupled with the fact that Britain had lent or spent much of its pre-war wealth during the war, and the demand of the British public—and in particular, the new Labour Party–for welfare benefits, the result was Chancellor Churchill sought to impose more than the normal economies on his colleagues and Britain’s creditor across the Atlantic.

The curious fact, though, was that Churchill’s nominal adversary Andrew Mellon, Treasury Secretary to Presidents Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover, was both profoundly Anglophile and hardly unsympathetic to Britain’s dilemma. One of Eicher’s virtues, indeed, is that she does not make Mellon out to be the villain of the piece. The claims that Mellon faced, indeed, were almost as taxing as those confronting Churchill. In a story that now reads mostly like a happy fairy tale, Mellon believed in running a budget surplus and paying down the national debt, while facing a Congress that believed it had a role to play in making foreign policy—but which also, less happily, expected the loans American voters had made to be repaid.

Like many leading figures in the City of London, Mellon also believed that it was important for the debtor nations to make an honest effort – though not one so excessive as to destroy their finances or impede their ability to purchase American goods—to repay U.S. loans. The simple fact was that all the debtor nations would need to borrow more money in the future. As the U.S. was the only plausible source for most of those new loans, repudiating the old loans would run the grave risk of imperiling the willingness of American investors to make new ones.

Churchill understood all this very well—but both politically and personally, he remained a young man in a hurry. He was, until the fall of the Lloyd George coalition in 1922 and after he became Chancellor in 1924, a leading figure in governments that were committed, though with increasing doubts and caveats, to collecting on Britain’s own loans to the Allies and on German reparations—payments that were not forthcoming. Churchill’s decision to return Britain to the gold standard in 1925—a decision taken on expert advice, but of dubious wisdom—further tightened the financial screws. As a result, instead of relying on Mellon’s sympathy with Britain to secure a solution, Churchill chose a confrontational route.

Churchill is remembered as a friend, admirer, and ally of the United States. Over the long run of his life, he was all of those. But at times, and in particular in the 1920s, he was a sharp critic of American policy and, on occasion, of the United States itself. It was not just U.S. policy on war debts that irked him – he was just as annoyed by U.S. efforts to promote naval disarmament in ways that impinged on the ability of the Royal Navy to defend the Empire. If Churchill could be said to have had an anti-American decade, it was—not without cause—the 1920s.

But while his annoyance at U.S. financial demands was understandable, it was also unwise. With an occasional misstep, Mellon was eager to lower the temperature on the war debts question, and to arrive at a negotiated agreement as much out of the public eye as possible. It was Churchill who, feeling the injustice of repayment and wanting to save the cash for other causes, pressed his case and the tempo. While owing to Mellon’s reticence, there was not actually much Mellon in the public clash of Mellon vs. Churchill—Eicher overplays for the sake of a good title—Churchill was certainly up for a fight. His combativeness did not serve him well.

Eicher inclines towards the conventional wisdom: Senator Henry Cabot Lodge was simply out to sabotage the Versailles Treaty, the Germans were more or less innocent victims of post-war hyperinflation, and U.S. policy towards Europe as a whole was neither constructive nor sensible. This reflects the literature on which she relies, the most important works of which date from the 1970s and 1980s. Works such as Patrick Cohrs’ Unfinished Peace (2008) do not turn the 1920s into a brilliant success—the 1930s preclude that, and U.S. tariff policy is in any event impossible to defend—but these contemporary scholars make the case that U.S. policy was not quite so as blinkered as Eicher implies.

By the same token, Eicher focuses on her two protagonists, which gives her story its readability and drive, especially drawing as she does on extensive research in contemporary newspapers for the anecdotes that enliven her story. As a result, Eicher undersells the broader context—from just how remarkable it was, given its history, that the U.S. entered the Great War at all, to the wider political and financial constraints that Churchill confronted as Chancellor.

Both Mellon and Churchill come alive in Eicher’s narrative. But both also worked within boundaries that were even more limiting than Eicher allows. Delineating those boundaries would have added a layer of understanding of U.S. policy and, especially, made Churchill’s pushfulness more explicable. True, Churchill was never one to need a prod. But in the case of Britain’s war debts, his natural love of action was shaped not just by his character, but by considerations that appear only on the margins of Eicher’s story.

Mellon and Churchill were, in a sense, both ill-suited to be stewards of national finance. Mellon was experienced and dedicated, but as Eicher illustrates time and again, he was an awkward public defender of policies that could be sensible. Churchill, on the other hand, was thrilled to follow in his father’s footsteps as Chancellor, but as David Lough has made clear, his genius was never fully at home in the financial realm, and he was a bit too eager to make policy by means of public speeches. But together, the battle over war debts that they personified is a story well-told by Eicher, of two great men trapped by circumstances that both did their best to overcome.

Dr. Ted R. Bromund holds a Ph.D. in British history from Yale University. He is founder of Bromund Expert Witness Services LLC, which provides expert witness testimony for victims of INTERPOL abuse. Jill Eicher will be a featured speaker at this year’s Churchill Conference in Washington.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.

Oops! We could not locate your form.

Privacy