Bulletin #206 — Jul 2025

Mother Love

June 27, 2025

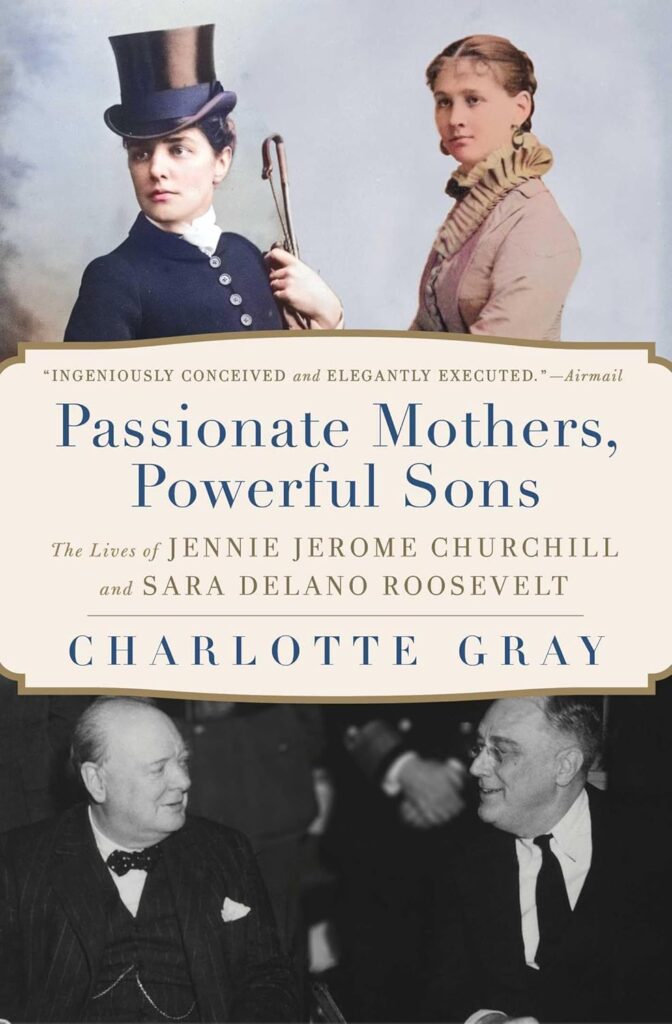

Charlotte Gray, Passionate Mothers, Powerful Sons: The Lives of Jennie Jerome Churchill and Sara Delano Roosevelt, Simon and Schuster, 2024, 405 pages, $17. ISBN 978–1668031998

Review by Ronald I. Cohen

When I had the opportunity to read the pre-publication text of Charlotte Gray’s Passionate Mothers, Powerful Sons, I was riveted by both the concept and the execution. As long as I had tilled the Churchillian fields, I had never taken the personal notice that Gray had, connecting the mothers of Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt, both not only American but born in the same year (1854), less than 100 miles apart in New York state.

Gray’s conception, focusing on the passionate mothers of the two supremely powerful democratic leaders of the Second World War, is not only original and brilliant but accomplishes the seemingly impossible: finding something new and perceptive to write about two of the most broadly studied individuals of the last century. Gray weavs together the parallel—but remarkably different—tales of Sarah Delano and Jennie Jerome as wives and mothers by exploring their dissimilar guidance of their famous sons’ futures.

Full disclosure: I know Charlotte personally; we both sit on the board of the Sir Winston Churchill Society of Ottawa. That said, the trade paperback issue of the work is now available, and my own immensely positive reaction to the book has been echoed in major periodicals such as the Wall Street Journal and The Literary Review of Canada.

2025 International Churchill Conference

Few statesmen of great moment have had as colorful a mother as Churchill, and, despite Churchill’s early disappointments in his mother, few men have shown the level of devotion and loyalty to their mothers as he did. Jennie Jerome was a celebrity in her day, and, as might be expected, her reputation has been continually re-evaluated. She has been disparaged as a reminder of Edwardian decadence, acclaimed for her unconventionality, censured for her profligacy, all while generally being applauded for her undeniable joie de vivre. Too frequently, though, many studies have approached her purely as “the mother of” rather than exploring her life on her own terms. And she has always been in the spotlight alone, without the counterpoint of a contemporary comparison.

Gray, however, has produced a double biography of Jennie and Sara Delano Roosevelt, mother of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The parallel lives of Sara and Jennie, two remarkable, strong-minded women who helped mold their sons in radically different ways, is therefore fascinating as a study in contrasts and for the insights it yields into the era’s two most formidable leaders. The two mothers grew up with the same constraints and prospects. Within a rigidly patriarchal society, women like them were expected to dress, marry, and breed well within the confines of their class. Up to a point, Jennie and Sara stuck to the traditional template. For example, each resisted the idea of votes for women until her son endorsed female suffrage.

Nevertheless, writes Gray, within those constraints, both women exercised more agency than one might expect. Both women shocked their parents with their choice of spouse. Jennie became engaged to the libertine Lord Randolph Churchill within three days of meeting him. Sara chose to marry the Delano’s Hudson Valley neighbor, widower James Roosevelt, despite a twenty-seven-year age difference. Both widowed while still in their forties, Jennie and Sarah displayed remarkable resilience, continuing to lead busy social and cultural lives rather than step quietly into the shadows. Their passionate devotion to their sons’ careers helped build in the young men the self-assurance that an ambitious politician requires.

Jennie and Sarah, nevertheless, had completely opposite personalities. Gray dives into each life at particular stages (childhood, courtship, marriage, motherhood, widowhood) to show how each woman faced challenges in her own way.

Sara, tall, dignified, and immensely wealthy, was a deeply conventional woman who never colored beyond the lines of proper protocol. Throughout her life she remained firmly rooted in the Hudson Valley and in nineteenth-century attitudes. After James Roosevelt’s death, she adopted widow’s weeds and never remarried. Instead, she focused her attention on “My Boy,” as she always referred to her only child, Franklin. Thanks to the fortunes she had inherited from both her father and her husband, she had the resources to bankroll Franklin’s political career and subsidize his White House expenses. A formidable organizer, she also played a large role in her husband’s marriage to Eleanor and reveled in the traditional role of grandmother to their five children. Not surprisingly, Eleanor always resented the fact that “Franklin’s children were more my mother-in-law’s children than they were mine.”

Dark-haired, curvaceous, and flirtatious, Jennie was a gregarious extrovert and skilled conversationalist, who happily entertained dinner guests with her skill at the piano. She was a chameleon, adapting to aristocratic circles first in France and then Britain. “You are the only person who lives on the crest of a wave,” her friend Lady Curzon remarked, “and is always full of vitality and success.” Constantly mired in staggering debts, she enjoyed numerous dalliances with lovers who were said to include an Austrian nobleman, several British noblemen, and the Prince of Wales, who admired American women because “they are livelier, better educated, and less hampered by etiquette…not as squeamish as their English sisters.” She married twice more after Lord Randolph’s early death, both times to men of Winston’s generation.

Most of all, however, Jennie ached for the kind of public role to which women rarely had access in her time. This led her to take several initiatives including founding a literary quarterly in London (the Anglo-Saxon Review, to which Winston contributed “British Cavalry” in March 1901) and fitting out and joining the nursing staff of a hospital ship to care for wounded British soldiers during the Boer War. While her two sons, Winston and Jack, were children, she was less present in their lives, leaving them to the care of nannies and boarding schools. Later, once Winston had become a boisterous and ambitious young man, she dedicated herself to the furtherance of his career through her unrivaled network of connections within London’s political, military, and Fleet Street elites. As Winston would famously write, “She left no wire unpulled, no stone unturned, no cutlet uncooked.”

Lady Randolph, as Jennie preferred to be known, had once hoped to be the wife of the British prime minister, but, after Lord Randolph sabotaged his own career, she shifted her ambitions to her son, for whom she foresaw a brilliant political career. “I believe in your lucky star,” she wrote to him while he was risking his life as a young army officer in northern India in 1897. But in May 1921, twenty years before Winston finally achieved the top office, she fell and broke her ankle. Gangrene set in, necessitating an amputation. “I must put my best foot forward now,” she quipped. Days later, she slipped into a coma and died at age sixty-seven.

Sara Roosevelt saw her beloved son first disabled by polio and then elected to the American presidency three times before her death in 1941, aged almost eighty-seven. At her son’s third inauguration, she proudly proclaimed herself “a mother of history.” The President’s staff noted that they had never seen FDR so emotional as when he lost her.

Gray makes a compelling case for reconsidering the roles of both these formidable women in their sons’ lives. She notes how the biographers of Churchill and Roosevelt, most of whom are men, have often disparaged their subjects’ mothers. Jennie has been “shoehorned into the wicked seductress stereotype—too colourful, too promiscuous, and too spendthrift,” Gray writes, while Sara has been saddled with a different “misogynist trope” as smothering and manipulative. Gray tells the stories of her subjects with a level of detail and immediacy that makes a reader care about who they were. “Maybe Sara was imperious. Perhaps Jennie was flirtatious. But is that the only way to remember two women who, despite the suffocating constraints of the time, took charge of their lives and worked hard to help their sons?”

Ronald I. Cohen CM MBE is author of Sir Winston Churchill: A Bibliography of His Published Writings.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.

Oops! We could not locate your form.

Privacy