Bulletin #180 — May 2023

A Churchill for Our Time

To view in full, right click and choose "View Image"

April 29, 2023

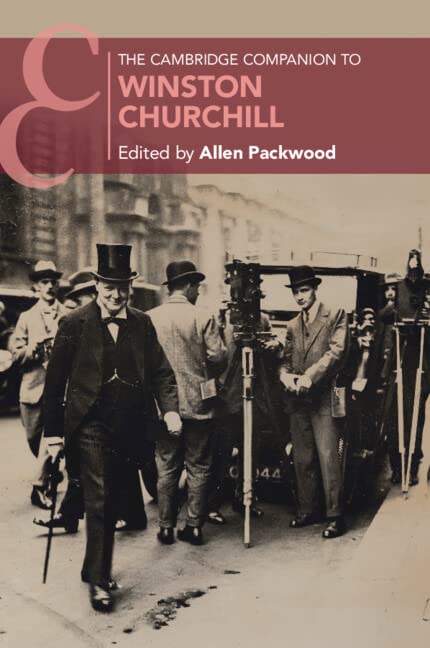

Allen Packwood, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Winston Churchill, Cambridge University Press, 2023, 418 pages, $29.99/£22.99. ISBN 978–1108840231

Review by SIR DAVID CANNADINE

“Reputation,” Shakespeare makes one of his characters remark, “is an idle and most false imposition, oft got without merit and lost without deserving”—an observation that should be pondered by anyone or any group in our own time who want to pull statues down or, indeed, to put them up. All his life, Winston Churchill was fascinated by the matter of fluctuating reputations, both other people’s and also his own. When writing the biography of his father, Lord Randolph, young Winston noted that the “party standards” by which politicians were judged during their lifetime bore no necessary relation to what might be their “ultimate reputation,” whenever that would happen, and whatever it would be. And he made the same point in his eulogy of Neville Chamberlain late in 1940: “In one phase men seem to have been right; in another they seem to have been wrong. Then again, when the perspective of time has lengthened, all stands in a different setting. There is a new proportion, there is another scale of values.” These were—and are—very wise words.

Churchill’s own reputation underwent extraordinary vicissitudes during his exceptionally long, often highly controversial and eventually illustrious career. By the time he entered parliament, he was already regarded as a brash, egotistical man in a hurry, and most of his colleagues in the Commons, on both sides of the House, thought him exceptionally ambitious and also, like his father before him, wayward, unstable and lacking in judgment. There was, then, little surprise and much rejoicing when it seemed, during the First World War, as though his career had crashed into irretrievable ruin in the aftermath of the Dardanelles disaster, for which it was believed he bore the brunt of the blame.

Thereafter, during the 1920s, Churchill laboriously sought to rebuild his reputation, although his decision, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, to return Britain to the Gold Standard, and his belligerent behaviour at the time of the General Strike, suggested that his judgment had not altogether improved. And during the 1930s, his diehard opposition to the Government of India Bill, his hostility to appeasement when offering no viable alternative policy, and his misguided support of King Edward VIII at the time of the abdication crisis, offered further ammunition to his critics.

2024 International Churchill Conference

Only in 1940, and seemingly against all the odds, did Churchill obtain the keys to 10 Downing Street and become the hero he had always dreamed of becoming, enjoying extraordinary popular support in Britain for the duration of the Second World War, and soon being widely acclaimed as “the saviour of his country.” As Max Hastings would later write, it was—and is—impossible not to be impressed and overwhelmed by “the sustained magnificence” of Churchill’s performance. But for all its undeniable gratitude, the British electorate was right in its instincts that, having won the war, he was not the man to make the peace. It was only towards the very end of his long life that Churchill became venerated as “the greatest Englishman of his time,” given the most elaborate state funeral in St Paul’s Cathedral for a non-royal since Wellington and Nelson, commemorated with statues in the lobby of the House of Commons and in Parliament Square (as well as elsewhere in the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world), and remembered with a prominent memorial stone in the threshold of Westminster Abbey.

This late-life apotheosis was in many ways fitting and deserved, but it was strikingly at variance with Churchill’s reputation before the Second World War. Even in his later years of fame and greatness, there were still doubters, their skepticism having been borne out by the deplorable election broadcast he delivered in 1945 in which he claimed that if the Labour Party won, Britain would soon be ruled by “some form of Gestapo”—an unforgivable slur on those members of the Labour Party who had served loyally and patriotically in the great wartime coalition. Cartoonist David Low’s response, by turns moving and perceptive, was to depict “Two Churchills: the one the acclaimed and admired ‘leader of humanity,’ who had led the battle against fascism and dictatorship, the other the wayward, disgruntled and rejected ‘party leader,’ the former saying to the latter: ‘Cheer up! They will soon forget you but they will remember me always.’”

Indeed, one way of understanding the ups and downs of Churchill’s posthumous reputation is that the balance has been constantly shifting between what has been admiringly remembered (or mis-remembered) about him, and what was disparagingly forgotten (but has recently been rediscovered). Instead of seeing the whole of his life through the prism of his leadership during the Second World War, this means that we can now—and should—see his brave and brilliant leadership during the Second World War in the broader and more complex context of his life as a whole.

Today, Churchill’s posthumous hold on the imagination of many Britons remains extraordinarily strong, perhaps because in many ways the Second World War was truly the nation’s “finest hour,” when Britain and its Empire played its last great starring role on the stage of history, and when it came out on the right side and the winning side. It is not clear that any other country remains as preoccupied with the Second World War as the United Kingdom, and Churchill has certainly been the long-lasting beneficiary of that preoccupation, which his own extraordinary leadership, and his hugely influential six-volume history undoubtedly helped to embed and perpetuate. In a poll conducted by the BBC in 2002, to establish the greatest Briton of all time, and which attracted a million votes, Churchill came out top. Boris Johnson did all he could to present himself as a latter-day Churchill—a presumptuous and preposterous claim to affinity that Nicholas Soames rightly scorned, but significant, nonetheless, and more revealing about Churchill’s fame than Johnson’s failings.

Meanwhile, in the United States, Churchill has been repeatedly invoked in the years since his death by those who (mistakenly) believe that he always stood up to dictatorships and never gave into aggression, thereby justifying such misguided American ventures as the Vietnam War and the invasion of Iraq. No American president wants to be accused of being a Munich-like appeaser. All of which is simply another way of saying that, almost sixty years after his death, Churchill is still very much in the news. David Low’s “always” is a long way off; but Churchill is still being much “remembered” now, and often in a positive and appreciative light.

Yet Churchill had scarcely been buried when the revisionists got to work, among the first in the field being Robert Rhodes James’s brave and pioneering book, Churchill: A Study in Failure, 1900–1939 (1970). As more archival material became available, his own account of the Second World War was modified in many ways; and the late-life picture, that Churchill himself had helped create, of someone who was unfailingly and infallibly right, and without fault or flaw of any kind, also came in for significant revision, as his errors of judgment and temperamental failings were uncovered and explored. Pace David Low, the “second” and lesser Churchill is no longer “forgotten,” and rightly so, but instead is being subjected to serious and sometimes critical scholarly scrutiny.

There have also been broader changes which have also altered perceptions. In the United States, Churchill has little to say to a Democratic party preoccupied with issues of gender and race, while in the United Kingdom, the growing concern with the disputed legacy of the British Empire often casts Churchill in a negative light, as a self-proclaimed imperialist and as someone whose views on South Asians were reprehensible, not just by the standards of our day, but by the standards of his day, too.

As was so often the case before 1940, Churchill is once again very controversial, the subject of vigorous (and sometimes vituperative) academic debate and caught in the crossfire of the culture wars in the media that show no sign of abating. It was, then both brave and timely that Allen Packwood, Director of the Churchill Archives Centre, should take on the task of editing The Cambridge Companion to Winston Churchill, which aims to serve as “an introduction, overview and guide to the life of one of the most researched, debated and contested figures of our recent past.”

Significantly, and unsurprisingly, it is very different in its tone and its contributors from the earlier volume, edited by Robert Blake and William Roger Louis, which in 1993 concluded that “when subjected to scrutiny in the light of the historical evidence, Churchill emerges with both his integrity and his greatness intact.” This book, by contrast, brings together contributions by many younger scholars, born long after Churchill’s death, and gives full attention to such controversial episodes in his career as race, empire, India, Ireland, and his support for aerial bombing during the Second World War.

As he recedes into the distance, moving from memory to history, the Churchill who emerges in Packwood’s Companion was more fallible, more complex, and more time-bound than the earlier, heroic interpretations suggested, and than the current denunciations admit and disparagements allow. Yet, and perhaps paradoxically, the result of the essays gathered together here is to make Churchill more interesting, more nuanced, more credible, and more human than ever before: this important book gives us Churchill not only in his time, but also in our time, too.

Sir David Cannadine is Dodge Professor of History at Princeton University and a member of the Board of Directors of the International Churchill Society.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.