Bulletin #152 — Feb 2021

The Health of the Lion

February 1, 2021

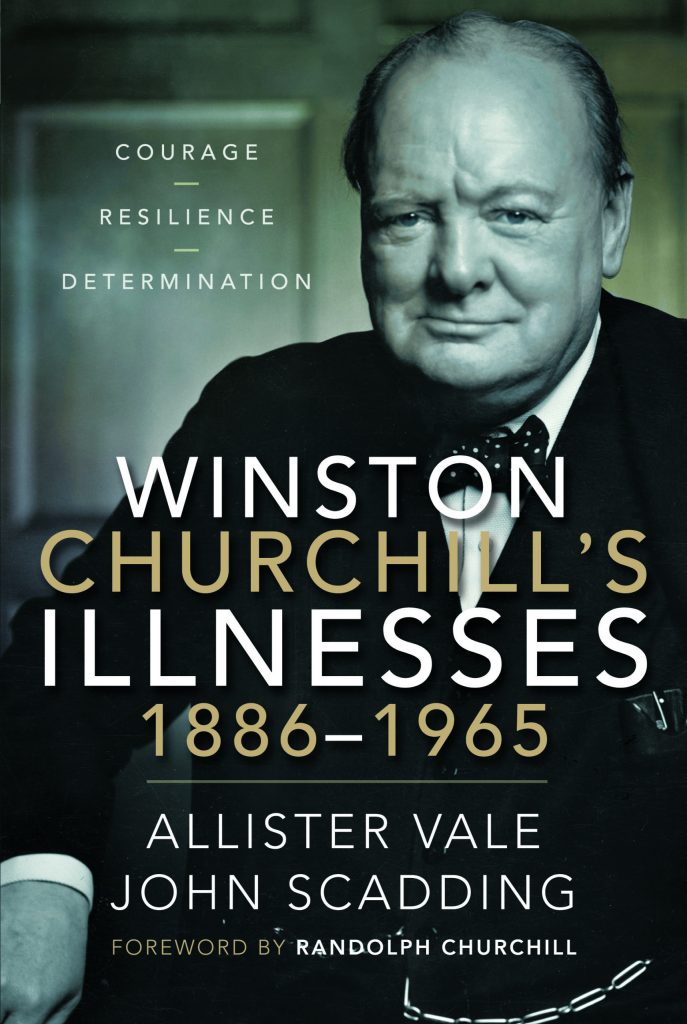

Allister Vale and John Scadding, Winston Churchill’s Illnesses 1886–1965, Frontline, 2020, 522 pages, £30/$52.95. ISBN 978–1526789495

Review by GAIL ROSSEAU

In Winston Churchill’s Illnesses, readers will be delighted to discover the definitive book on the health of one of the most important patients in modern history. We are treated to this magnum opus by two outstanding medical professionals, who have labored for more than three decades to get the story and tell it right—a story that many thought could never be told.

Readers familiar with this subject may recall that a furious public debate over patient confidentiality ensued when Churchill’s personal physician, Charles Wilson (Lord Moran), published his own book in 1966, just a year after the death of his famous patient. For their much more objective and complete account of Churchill’s illnesses, Allister Vale, Consultant Pharmacologist from the University of Birmingham, and John Scadding, Consultant Neurologist Emeritus at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery at Queen Square, London, meticulously and patiently secured multiple personal, institutional, and archival permissions and combed thousands of source pages to create a most important contribution to the Churchill literature.

Newly available medical notes from such medical luminaries of the time as Lord Moran, Lord Brain, Sir John Parkinson, and Dr. Thomas Hunt provide a lively record of Churchill more compelling than any contemporary medical drama. The stories create vivid images: a young private duty nurse is informed that the patient—the Prime Minister—does not wear pajamas; three eminent medical experts solemnly discuss Churchill’s health, as the patient chuckles, his parrot landing on their shoulders and pecking their ears. Churchill’s signature good humor lightens every sick room with laughter, and his eloquence elevates dreary infections to heroic battles.

Like any good doctors, the authors build their patient’s history on facts and are guided by the expert opinions of physician specialists. This dogged insistence on veracity is best appreciated in the useful feature, “Medical Aspects,” which appears at the end of each chapter. They examine the symptoms and treatment of each malady from both a contemporaneous and a modern perspective, which is very helpful for general and medical readers alike. The authors’ pronouncements on the medical care provided by healers from Churchill’s era is kind but honest. Care is wisely judged by the state of knowledge and available treatments at the time.

Importantly, the dispassionate presentation of Vale and Scadding allows a number of myths about Churchill’s health to be debunked. For example, he did not have a heart attack in the White House in December 1941. He was examined by Sir John Parkinson, Britain’s most eminent heart specialist, three weeks later. Both the physical exam and the electrocardiogram were normal. Churchill was not clinically depressed. Despite a well-known tendency toward crying in public and multiple personal and world crises which caused him despair, Churchill’s behavioral health is objectively examined and found to meet none of the criteria—in his day or ours—for major depressive disorder, unipolar depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, or cyclothymic disorder.

Likewise, the most famous illness ascribed to Churchill, alcoholism, is similarly rebutted in an entire chapter titled “Was Churchill an Alcoholic?” A Review of the nursing “Intake and Output” record of the famous patient during a serious bout of pneumonia in 1943 confirms Churchill’s legendary alcohol consumption even when ill: “Champagne 10 oz., Brandy 2 oz., whisky and soda 8 oz…clearly on the mend!” The topic is assiduously explored, including a methodical thirty-year search for all known reports of him being worse for drink. Only two such occasions are reported. One was during the Tehran conference in 1943, when Churchill and Anthony Eden opted to decline a limousine ride back to their legation, choosing to walk in order to enjoy the clear and starry night. Both men benefitted from a helping arm to hold them steady. On another occasion, 6 July 1944 (just one month after D-Day), Churchill was very tired as a result of a speech in the House of Commons concerning the flying bombs; he tried to recuperate with drink, resulting in bad-tempered behavior and a “deplorable evening” according to Field Marshall Lord Alanbrooke. Symptoms of alcohol withdrawal were never reported. Readers who, like Sir Winston, enjoy potent potables are likely find that this chapter will enliven future cocktail hours. The last word on the topic belongs to Churchill: “I could not live without champagne. In victory I deserve it. In defeat I need it.”

There are two important take-aways from reading this book. The first is that, during an era when the entire world is weary of a persistent pandemic, it is encouraging to read these accounts of the best possible care provided by Britain’s greatest doctors for the nation’s most important patient and recognize how far we have come since Churchill’s day. We are shocked at the treatments that passed as good medicine not so many years ago. Thus, we learn that Winston was treated with oral and rectal brandy for pneumonia—at age eleven! Electrotherapy was used in a vain attempt to try to prevent his recurrent shoulder dislocations. After a battle in Africa, Churchill was asked to donate skin from his own arm to a fellow soldier whose injuries required a skin graft. Young Winston willingly obliged, despite feeling “flayed alive” in what is clearly not accepted medical practice today. An inguinal hernia repair, now routinely performed with a minimally invasive laparoscope, resulted in an eight-inch incision and painful recovery. Churchill’s many strokes were treated with aminophylline and niacin and a number of other drugs that find no place in modern cerebrovascular care.

Most shocking to modern medical sensibilities is the elevated risk of mortality from pneumonia, estimated at 40% for a man of Churchill’s age at the time. We are reminded that the Speaker of the House of Commons, Edward FitzRoy, was also taken ill with pneumonia on the same day as Churchill in 1943—and died. Antibiotics were new, in short supply, and poorly understood; faced with the Prime Minister’s life-threatening pneumonia in North Africa in 1943, none of the experts treating Churchill had experience with systemic penicillin. A pathologist was needed to fly in from a continent away to look at a sputum sample to make the diagnosis that would direct the appropriate medical treatment.

But it is the extraordinary response of this man to ailments any one of us could encounter, which makes the story of Churchill’s health so compelling. He famously said, “Courage is rightly esteemed the first of human qualities, because it is the quality which guarantees all others.” This detailed account of Churchill’s health and the many personal hazards he faced forces us to reflect on how his example speaks to our own lives.

Take his lifelong orthopedic problem, for example. As a young soldier in 1896, a boat transfer in rocky seas in the port of Mumbai dislocates his dominant right shoulder, a recurrent condition that would plague him all his life. Yet he loves his sport—polo—so he continues to play, even with his elbow strapped to his side. Churchill writes that “at irregular intervals my shoulder has dislocated on the most unexpected pretexts; sleeping with my arm under the pillow, taking a book from the library shelves, slipping on a staircase, swimming, etc. Once it very nearly went out through too expansive a gesture in the House of Commons.”

We learn from an orthopedic shoulder expert that extensive analyses of the much-photographed Churchill show that he adopted a habitual cautionary posture to avoid the risk of instability of his right upper extremity. This certainly caused frequent pain and anxiety to a politician, a profession which requires shaking hands for a living! Yet Churchill finds himself grateful that the condition caused him to use a pistol instead of a sword during the great cavalry charge at Omdurman in 1898. He reflects that, had he not injured his shoulder, “my story might not have got as far as the telling….One must never forget when misfortunes come that it is quite possible they save one from something worse.”

In 1922, a black and gangrenous appendix was removed though a five-inch incision in an emergency operation at the height of a political campaign. Despite the proxy campaigning of his devoted wife, Clementine, Churchill lost that election: “In the twinkling of an eye, I found myself without an office, without a seat, without a party and without an appendix.”

Visiting New York City in December 1931, Churchill looks the wrong way while crossing Fifth Avenue and is hit by a car, sustaining serious injuries, which include multiple fractures and a hemothorax, which is a bloody effusion around the lung probably caused by rib fractures. Taken to Lenox Hill Hospital, Churchill cables the Daily Mail: “Have complete recollection of whole event and believe can produce literary gem about 2400 words.” By March, Churchill is able to tell a radio interviewer, “It’s not a jolly thing to be cut down by a motor car at 30 miles an hour….I was very lucky in the way it hit me.”

But it is the long series of strokes, beginning in 1949 and recurring until the terminal event more than fifteen years later, which are most affecting. Churchill initially describes the episodes to Lord Moran by saying, “everything went misty” and that he felt “muzzy-headed.” The strokes recurred and progressed, with serious deficits recurring just two weeks before the election in 1951 that returned Churchill to Downing Street. He told his physician, “I am not afraid to die, but I want to do this job properly.” Churchill’s cerebrovascular troubles continued during his second stint as Prime Minister. On 24 June 1953, he presided over a Cabinet meeting with almost unbelievable heroism: none of the ministers present were aware that Churchill had suffered a major stroke the night before. Indeed, no one even noticed anything wrong with the Prime Minister. Yet, in an examination that morning, Lord Moran confirmed that Churchill’s mouth sagged on the left and that he was unsteady on his feet. The physical findings and diagnosis of stroke were confirmed by Lord Brain after the Cabinet meeting. Yet Churchill simply asked his medical team, “Is there an operation for this kind of thing? I don’t mind being a pioneer.”

Lord Moran, remarked after one of his patient’s remarkable recoveries after a stroke, “Winston has nine lives.” How lucky are we to have this vivid account of each of those lives. By their scholarship, Vale and Scadding have given us a gift. Churchill’s courage, grace, and humor during times of illness provide an example of true greatness to which we can all aspire in our everyday lives.

Watch an interview on this topic with International Churchill Society Executive Director Justin Reash, Dr Rosseau and panel on the ICS YouTube channel here.

Gail Rosseau is Clinical Professor of Neurosurgery at the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, where she is actively involved in the National Churchill Leadership Center.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.