Bulletin #152 — Feb 2021

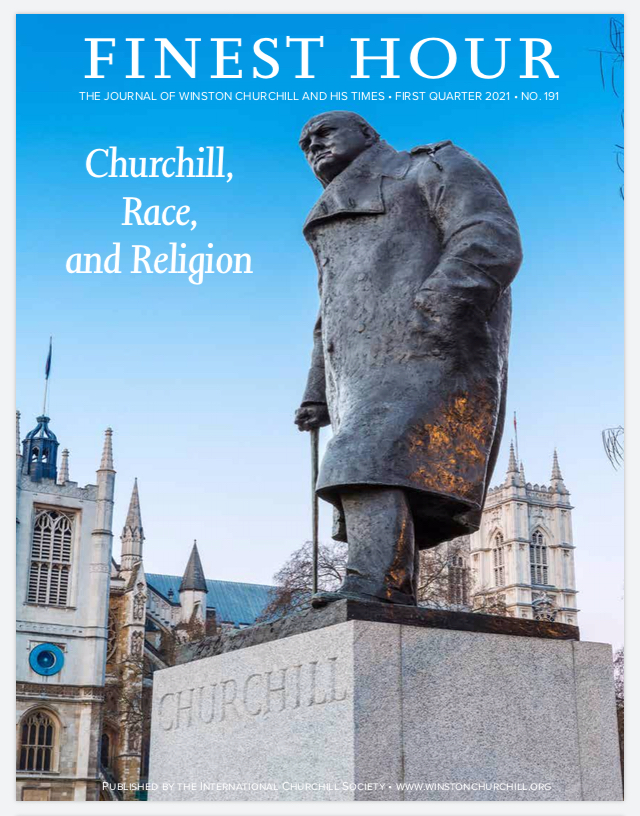

Churchill, Race, and Religion

February 1, 2021

By The Rt. Hon. the LORD BOATENG

The first issue of Finest Hour in 2021 looks at the controversial subjects of Winston Churchill’s views on race and religion. Lord Boateng, Chairman of the Churchill Archive Trust has provided the following foreword to the issue.

We are in the midst of a world-wide pandemic that presents the biggest challenge to global polity since the Second World War. The disparities in the distribution of resources and challenges in governance between and within nations and peoples seem wider than ever. Men invade the US Capitol building wearing T-shirts that celebrate Auschwitz, and, in Westminster, police are called upon to protect statues of Winston Churchill, Abraham Lincoln, Nelson Mandela, and Mahatma Gandhi from warring protagonists. It has never been more important, then, to find common values rooted in the highest ideals that unify us in a common cause—not least against all those forces that threaten our shared humanity and the institutions that protect us all.

This year will mark the eightieth anniversary of the Atlantic Charter, in which Prime Minister Churchill and President Franklin D. Roosevelt strove to arrive at just such an articulation of the principles upon which the world could come together against a common enemy and be reconstructed, as Churchill articulated in his broadcast of 24 August 1941, upon “the broad high road of Freedom and Justice.”

Roosevelt committed himself to “everlasting “and “angry defence” against all comers “of the four freedoms” [of speech and worship, from want and fear] and the “Atlantic Charter” with its commitment to “self determination for all peoples,” while decrying those who described these ideals as “nonsensical and unattainable” and who were just as likely to have said the same thing against the Declaration of Independence.

Central to the defence of those values must be the search for historical accuracy, evidence-based analysis, and a commitment to academic freedom. In that spirit, my task and that of my fellow trustees of the Sir Winston Churchill Archive Trust, which I now have the honour to chair, is to protect, preserve, and promote access to the collection acquired by the nation of papers and records pertaining to this remarkable man and his life. We hope in so doing to bring about for all peoples a better understanding of his life and times and the shaping of our modern world.

I therefore warmly welcome this edition of Finest Hour. The editor and distinguished contributors have not run away from the potential and actual controversy surrounding its subject matter. I was not brought up in a household that forbade the discussion of politics and religion around the dinner table—on the contrary, as it happens, a fact that no doubt shaped my own subsequent career as a lawyer, politician, and diplomat. Race in any event we could never escape, living as we did in a biracial family in both pre- and post-colonial Africa and later in the United Kingdom. This fact, whilst it did not guarantee quiet and harmony, did make for lively and passionate conversation and a healthy respect for differences. These erudite and well-reasoned essays will, I have no doubt, provoke just that and are all the better for it.

Sir Winston did not run away from controversy in his life and would not expect anything less in that which has followed. We do owe him and each other, however, civility and respect in the conduct of those arguments—not least, since we owe to him and the global anti-fascist fight, which he helped lead to such good effect, the secure freedom to hold those arguments at all.

The newly emergent country Ghana, in which I was brought up, referred back directly to the Atlantic Charter and to Churchill’s broadcast in its aftermath in its coat of arms and to that “broad highroad” when it had emblazoned on the Triumphal Arch erected to mark its Independence in 1957 the motto “Freedom and Justice.” I recall pointing this out many years later to Lady Soames, Sir Winston’s daughter. She was a much and rightly loved figure in newly independent Zimbabwe, remembered to this day for her personal commitment during her service in that country to those very principles.

There is so much of interest in these essays. Churchill’s relationship with Judaism, Islam, and Christianity all feature. These are less well known than his self-avowed imperialism, which he was obliged over time to moderate, not least because it came up against the principle of self-determination, to which he had come also to subscribe in the Atlantic Charter. We are reminded in one of the following essays that Churchill’s favourite hymns were sung in the church service that accompanied its signing. It is worth noting, then, that one of these contains the verse, “Time, like an ever rolling stream, / Bears all its sons away. / They fly forgotten as a dream / Dies at the op’ning day.”

Time indeed passes, as do men, but the challenge to the four freedoms and the continuing underlying sources of conflict that the Atlantic Charter sought to address in its principles remain as issues in this world to this day. So long as they do, Sir Winston’s life and his archive will retain their fascination and relevance.

The Right Honourable the Lord Boateng of Akyem and Wembley PC DL is Chairman of the Trustees of the Sir Winston Churchill Archive Trust. He served as Member of Parliament for Brent South from 1987 to 2005 and became the United Kingdom’s first black cabinet minister when he was appointed Chief Secretary to the Treasury in 2002. He then served as High Commissioner to South Africa from 2005 to 2009 and was appointed to the House of Lords in 2010.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.