Bulletin #145 - Jul 2020

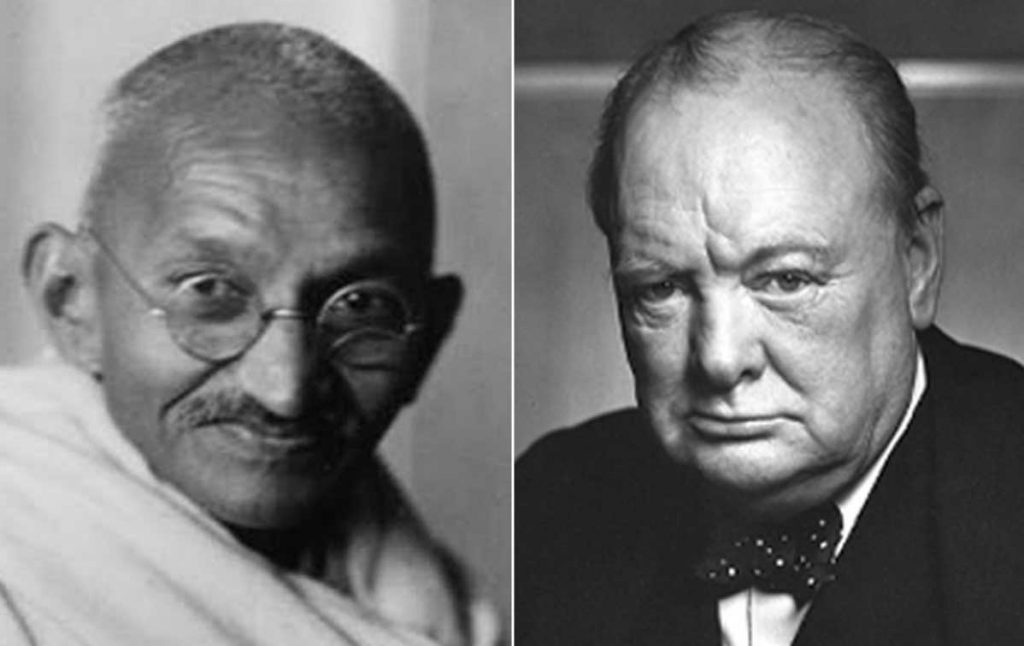

Churchill and Gandhi Stand for Tolerance

Churchill Image: Karsh Estate

June 30, 2020

Mahatma Gandhi was murdered for agreeing with Winston Churchill. Today statues of both men stand in London’s Parliament Square. In early June 2020, the statue of Churchill was vandalized by a mob of protestors. The name “Churchill” engraved on the plinth was crossed through with black spray paint, and the words “was a racist” were added beneath. For good measure, the mob also vandalized the nearby statue of Abraham Lincoln, the Great Emancipator, who was murdered by an avowed racist.

Churchill is best known today for leading a coalition of nations in the successful effort to defeat the institutionalized racist government of Nazi Germany. He is also remembered for having once opposed self-government for “India,” as all of South Asia was referred to in Churchill’s time. How do we reconcile the two positions? By digging deeper than most protestors will ever take the time to do.

Having been stationed in India as a young officer in the British Army, Churchill knew well that the region comprised countless sects, ethnicities, and religions many with a long history of mutual antipathy. Churchill did not believe that all of South Asia could ever be transformed into a single independent state. Neither did Mohammad Ali Jinnah, whose leadership of the All-India Muslim League saw to the creation of a separate Pakistan for “India’s” Muslim minority.

Churchill, Gandhi, and Jinnah all believed that independence would lead to discrimination against India’s religious minorities. Churchill wrongly believed that continued British rule could avoid such a calamity. Gandhi rightly believed that the Indian people would have to work the problem out for themselves, and Jinnah chose a political solution to a social problem.

As all three men feared, independence led immediately to massive sectarian violence. Countless people were killed as large populations were forcibly relocated. Gandhi was heartbroken. Following independence in 1947, he said, “India has never followed my way.” Shortly afterwards he was assassinated by a Hindu fanatic enraged by the Mahatma’s call for religious tolerance, the very issue on which he and Churchill completely agreed.

During the campaign for Indian self-government in the 1930s, Churchill spoke harshly about Gandhi. The Mahatma preferred to recall a time three decades earlier when the two men met face to face and were in agreement in their opposition to the creation of racially discriminatory laws in South Africa. Churchill had also distinguished himself in 1919 when he took what was then the politically unpopular decision to condemn the British general responsible for directing the Amritsar massacre of unarmed Indian civilians.

Above all, Churchill was dedicated to representative democracy. He accepted defeat when the Government of India Act was passed by Parliament in 1935, granting India dominion status in anticipation of its independence, and invited one of Gandhi’s leading supporters, Ghanshyam Das Birla, to have lunch with him and Mrs. Churchill—not the action of a militant racist.

During their two-hour lunch, Churchill told Birla that “Mr. Gandhi has gone up very high in my esteem since he stood up for the untouchables.” While Churchill maintained that he still did not like the new bill, he wanted the Indians to make a success of it, defining success as “improvement in the lot of the masses, morally as well as materially.” “Make it a success,” Churchill concluded, “and if you do I will advocate your getting much more.”

In recent years, Churchill has been charged with deliberately neglecting the tragedy of the 1943 Bengal Famine. The famine resulted from the combined disasters of a cyclone that destroyed much of Bengal’s harvest and the Japanese invasion of South Asia—an invasion intended to supplant the British and not to liberate the locals from imperial rule.

Churchill, in fact, made timely and good faith efforts to fight the famine. At the height of the Second World War, however, there was simply not enough shipping to provide a sufficient relief of food supplies. All Allied ships were vulnerable to attacks by Axis submarines. The British and Irish people themselves were going short.

Following Churchill’s death in January 1965, the President of India, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, wrote Queen Elizabeth II to say, “It is with profound sorrow that the Government and people of India have learnt of the passing of the Rt. Hon. Sir Winston S. Churchill, the greatest Englishman we have known.” During the war, when Churchill was Prime Minister, Radhaskrishnan had been a professor at Oxford.

This is not the first time this particular Churchill statue has been vandalized, and most likely it will not be the last. Its prime position on the corner of Parliament Square directly facing the clock tower that is home to Big Ben gives it a prominence that it was fully intended to have. Protests go with the territory, and it is impossible to imagine that Churchill would have preferred his statue to be tucked away in a quiet corner. He rightly stands in the center of the public eye.

The simple fact is that without Churchill’s immense achievements in the cause of freedom during the crucial year 1940, the fascists would likely have won the Second World War. Today’s protesters should remember that their liberty to protest was secured and defended by the people whom Churchill was honored to lead. If today’s society is to see further than people did in Churchill’s age, it will be because we stand on the shoulders of a giant.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.