Bulletin #139 – Jan 2020

Churchill’s Man in Hollywood

January 4, 2020

Review by DAVID FREEMAN

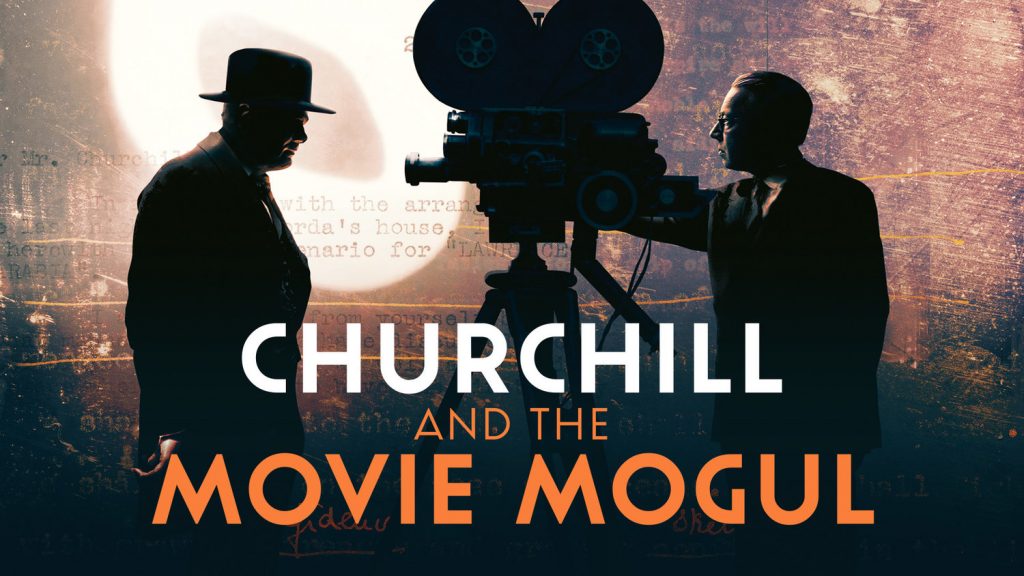

Churchill and the Movie Mogul, a documentary film by John Fleet, January Pictures, 2019, 60 minutes.

Winston Churchill loved movies, and for about fifty years now movies have loved Winston Churchill. He has been portrayed by many of the cinema’s biggest stars on both film and television. John Lithgow’ portrayal in season one of The Crown proved so popular that he has now been brought back by popular demand to reprise the role in the first episode of season three even though this has required some ahistorical contrivance to accomplish.

How appropriate then that a British filmmaker has finally made a documentary about the entirely true story of Churchill’s friendship with the founder of the British film industry! Alexander Korda was a Hungarian immigrant who fled the persecution of the Jewish people in his homeland during the 1920s. He embraced his adopted nation with panache naming his company London Films and using Big Ben as the studio’s calling card. He also took to smoking Churchill-size cigars.

Korda’s first box-office smash, The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933), won an Oscar for Charles Laughton and the praise of Churchill, who stirred to the King’s call for tripling the size of the fleet. “To do this will cost us money Sire,” says the King’s counselor. “To leave it undone will cost us England!” rejoins the King. Against the backdrop of the Nazis coming to power in Germany only a few months before, the tone of the film explains why Korda and Churchill became such fast friends.

In his analysis of Churchill’s finances, David Lough has shown that it was from selling the film rights to his books that finally made Churchill financially secure (see “Churchill and the Silver Screen: Film Turns the Tide” in FH 174). It was Korda who bought those rights. Korda also hired Churchill at a handsome fee as an assistant-producer and historical adviser for a planned (but never made) documentary about King George V to commemorate the King’s silver jubilee in 1935.

The relationship between Churchill and Korda during the 1930s and right up to the attack on Pearl Harbor forms the heart of the documentary Churchill and the Movie Mogul—and rightly so, for this was no idle friendship. Churchill and Korda were actively supporting one another in a sustained propaganda effort. They wanted to show through entertaining films that Britain historically and successfully stood against tyranny and thereby rally people around the world to support opposition to Hitler.

Fire Over England (1937), another box-office smash, did not want for subtlety. Although it stars Churchill’s favorite actress Vivien Leigh and her husband Laurence Olivier, it is Flora Robson’s Queen Elizabeth I who steals the film when she rallies her people at the approach of the Spanish Armada: “Not Spain, nor any Prince of Europe shall dare to invade the borders of my realm!” The film came out nearly a year to the day after Germany remilitarized the Rhineland.

There followed Korda’s “Empire trilogy” starting with Sanders of the River, 1936; The Drum, 1938; and finally The Four Feathers (1939), a colossal, full-color extravaganza that recreated one of the most famous episodes from Churchill’s own early life: the charge of the 21st Lancers at Omdurman. All this glorification of Britain got to be too much for some who suspected an ulterior motive. America First leader Charles Lindbergh blamed “British and the Jewish” elements for the fact that cinemas “soon became filled with plays portraying the glory of war.”

Though expressed in shamefully racist terms, Lindbergh’s views were not far wrong. Churchill and Korda were working together. Shortly after Churchill became Prime Minister in May 1940, Minister of Information Duff Cooper scheduled an “urgent meeting” with Korda. The movie mogul was to go to Hollywood to make an “American” propaganda film.

The resulting motion picture, released in March 1941 as Lady Hamilton in the UK and in April as That Hamilton Woman! in the US, reveals Churchill’s clearest involvement in propagandizing through film. With the war on, Korda’s own Denham Studios (it took a direct hit during the Blitz) had limited resources compared with what the producer could access in California. During production Churchill sent telegrams overseas to the producer with suggestions on how to proceed.

Once again starring Olivier and Leigh, the film told the story of Lord Nelson and the woman he loved culminating with the Battle of Trafalgar. Audiences could hardly fail to notice the similarity between Churchill’s own speeches of that era and Nelson’s verbal fusillade in the film when he declares, “you cannot make peace with dictators, you have to destroy them, wipe them out!”

That Hamilton Woman! became the fifth highest grossing film of 1941. But success came at a price. In September of that year, the US Senate commenced hearings investigating “Propaganda in Motion Pictures.” Korda’s body of work formed Exhibit A. Isolationist members of Congress—in truth, this was nearly all of them at that time, Democrat and Republican alike—lined up to challenge Korda’s bona fides.

The end result of these proto-McCarthy hearings never became known. Senators were unwittingly giving hostages to fortune since the whole business took place even as the Japanese plotted their attack on Pearl Harbor. Following December 7, Congress immediately dropped all inquiry into British film propaganda and enthusiastically welcomed Churchill to speak before a joint session on the day after Christmas. Just a few months later and upon Churchill’s recommendation, Korda received a knighthood, the first film producer to be so honored.

As a cinephile, John Fleet came upon the subject of his documentary while studying in France. Appreciating the serious attention the French give to their film heritage, Fleet recognized that British cinema lacked a similar tradition. Researching the origins of Britain’s film industry brought him to Korda and thence to Churchill. In filmmaking, however, coming up with ideas is the easy part. Getting ideas turned into film is the real challenge.

Fleet’s project took off when he recalled that actor, writer, comedian, and cultural savant Stephen Fry not only has a close association with the BAFTA awards, which he frequently has hosted, but a Hungarian grandfather. Given that the highest award presented by the British Academy of Film and Television Artists is named for Korda—and rightly so—Fleet suspected that Fry might have an interest in the father of the British film industry that could help get the documentary project launched.

And so it proved. After interviewing Fry, one of the many familiar faces who appear in Churchill and the Movie Mogul, doors started opening. Fleet also went through the archives to find interviews with many people now long since gone that helped to tell the remarkable story of how the greatest British Prime Minister and the greatest British film producer worked together to shape history by shaping public opinion.

The story did not end with the war. Korda wanted very much to show his gratitude to Churchill. In 1950 the film mogul wrote to the once and future Prime Minister to say, “I do want to give you a substantially good gift, so I’m giving you a cinema.” The former ground-floor dining room at Chartwell was fitted out with two 35 mm projectors and an RCA Victorphone high fidelity amplifier. Churchill enjoyed this gift—rare and kingly in those days—for the rest of his life (See “Let it Roll: Churchill’s Chartwell Cinema” in FH 179).

Korda died suddenly of a heart attack on 23 January 1956 at age sixty-two leaving his legal affairs in chaos. Churchill, by then fully retired at age eighty-one, owed much to his friend. Korda never did exercise the rights he acquired to turn any of Churchill’s books into films, and very likely the producer purchased the rights as a discreet method of supporting Churchill financially. But what of it? Churchill and Korda may have conspired to shape the future of history by dramatizing its past, but none can gainsay the justice of their cause, the results they achieved, or the merits of this magnificent documentary.

David Freeman is Editor of Finest Hour.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.