Bulletin #124 - Oct 2018

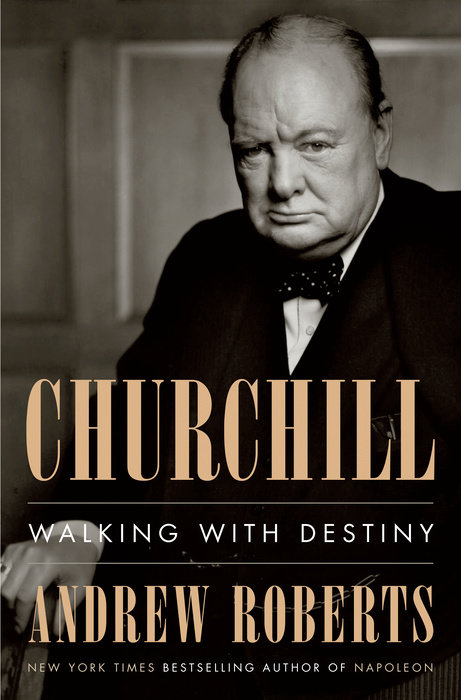

Churchill: Walking with Destiny

October 11, 2018

Review by JOHN CAMPBELL

Andrew Roberts, Churchill: Walking with Destiny, (US) Viking, $40, ISBN 978–1101980996; (UK) Allen Lane, £35, ISBN 978–0241205631; 1152 pages

Given his publisher’s claim that there have already been more than a thousand biographies of Churchill, not counting hundreds of specialist studies ranging from his war leadership to his taste in cigars, one’s first reaction to Andrew Roberts producing another thousand-page biography is incredulity. Can there really be anything new to discover or say? It is as if Churchill has become the Everest, which all biographers feel they must tackle before they hang up their pen, like great actors crowning their career by playing King Lear. Roy Jenkins wrote the last major biography when he was nearly eighty on the back of an equally substantial life of Gladstone; Roberts comes to him just four years after knocking off Napoleon. (But Roberts is only fifty-five, so one wonders where he can go next.) On the other hand, Jenkins has held the field for seventeen years, so maybe it is time for a big new reassessment for a new generation.

If so, Roberts has risen magnificently to the challenge. Jenkins’ book was an elegant tour-de-force of interpretation, but based almost entirely on his reading of the existing published sources, shrewdly refracted through a lifetime’s experience of politics. Roberts by contrast is a professional historian whose thorough research draws on a far wider range of sources, old and new. As a result, he has managed to assemble an enormous mountain of detail that will be fresh even to seasoned Churchillians.

First, he has gained access to a number of important new sources, most notably King George VI’s diary, which records the weekly lunches throughout the Second World War at which Churchill gave the King his frank assessments of the course of events; but also the diary of Marian Holmes, his favourite secretary for the latter part of the war; the minutes of the Other Club (the cross-party dining club Churchill founded with F. E. Smith in 1911, where he surrounded himself with his closest friends for the rest of his life); and the Chartwell visitors’ book, as well as other recently published goldmines such as the diaries of the Soviet ambassador Ivan Maisky—another to whom Churchill unburdened himself before and during the war with surprising freedom.

2025 International Churchill Conference

Second, Roberts’s bibliography lists nearly a hundred archives, around six hundred books, and another hundred scholarly articles and theses—and a finger in the footnotes shows that he has drawn fruitfully on all of them. On the one hand, he is up to speed with a lot of new, very recently published scholarship on different aspects of Churchill’s career (some of which first appeared in Finest Hour); and on the other he has trawled dozens of obscure and long-forgotten memoirs of secretaries, drivers, diplomats, and others for unfamiliar anecdotes and human glimpses, many of them very funny.

Third, he quotes extensively from Churchill’s own writings, including his enormous output of journalism—some of it trivial and eccentric, dashed off quickly for money, much of it powerful and prophetic (such as his grasp of the potential of nuclear energy in 1931), but all of it demonstrating his extraordinary breadth of interest and imaginative power of language—to the extent that his award of the Nobel Prize for Literature begins to seem not so incongruous after all.

Most remarkably, Roberts has managed to assemble all these sources into a well-constructed mosaic of vivid detail without getting bogged down for long in any one subject, but conveying the multifariousness of Churchill’s interests and activities on practically every page. His deft chronological narrative of huge world-shaping events is constantly lightened by personal touches that keep the focus on Churchill himself—his humour, his drinking, his tears and his unsinkable optimism. Roberts has no truck with the idea of Churchill as a depressive, pointing out that he only ever used the tern “Black Dog”—which has stuck to him—once. He likewise rejects the rumour that Churchill had an affair with Doris Castlerosse in 1933 (though he does concede that Clementine may have had a brief shipboard affair with Terence Philip in 1935). The book also includes twenty-four pages of excellent maps, so often lacking in books that badly need them, and a good index. The author thanks a number of people for their help, but credits no research assistants, which makes it simply as a feat of organisation a phenomenal achievement.

While not exactly hagiographic, Roberts’ view of his subject is unashamedly admiring: he is not afraid to write of Churchill’s “sublime” words in 1940, or his “noble heart” cracking at the end. As his subtitle announces, the book is built around the theme of Churchill as a man of destiny. Taking up Churchill’s own statement that his whole life up to 1940 had been “but a preparation for this hour and this trial,” it is divided into two parts of roughly five hundred pages each: The Preparation—up to May 1940, by which time Churchill was already sixty-five and had been at the top of British politics for nearly forty years—and The Trial, covering the war and (more briefly) his post-war premiership and final years.

Churchill clearly did have an extraordinary sense of destiny, expressed most astonishingly at the age of sixteen when he told a school friend that at some time in the future London would be in danger of invasion and “it will fall to me to save the capital and save the Empire.” All his life he showed a reckless disregard for danger, exposing himself gleefully to enemy fire in five wars—“Nothing in life is so exhilarating as to be shot at without result”—and surviving several car and plane crashes, as well as political setbacks that would have finished most careers. Nevertheless, the idea of destiny is a difficult one to take seriously unless you accept the full Calvinist notion of predestination. The most remarkable thing is that Churchill’s sense of destiny was ultimately justified.

What Roberts brings out particularly well is Churchill’s aristocratic sense of entitlement, his deep sense of history—admittedly a story-book history of kings and battles—and his belief in his place in it, and his immensely thorough self-education from an early age in the arts and techniques of writing and oratory, as well as in military strategy and weaponry, so that when he finally was called to lead his country in its moment of crisis he was thoroughly prepared. Ever since his painful experience at the Admiralty in 1914–15 he had been thinking seriously about civil-military relations in wartime, which was why he was determined to be Minister of Defence as well as Prime Minister, to avert a repetition of the friction between “Frocks” and “Brass Hats” which had marked the previous war. (“There will be no more Kitcheners, Fishers or Haigs.”) By comparison all his possible rivals were stumbling amateurs, which is why the Tory establishment that had loathed, distrusted, and disparaged him for years had no choice but to accept his succession to Chamberlain. There really was no alternative in May 1940. Destiny?

Churchill was often portrayed as an unprincipled careerist, but Roberts sees a lifelong consistency in his belief in the civilising mission of the British Empire, which he calls Churchill’s “secular religion.” (Churchill had no traditional belief in Christianity or an afterlife.) Of course by modern standards Churchill, like almost all his contemporaries, was a “racist,” in that he believed unquestioningly in the superiority of the white race (and the British in particular); but he was always genuinely, if paternalistically, concerned for the welfare of the peoples of the empire whom he believed it was Britain’s duty to protect and raise—albeit slowly—to European standards. He unhesitatingly condemned the Amritsar massacre of 1919 (“a monstrous event which stands in singular and sinister isolation”); and even his diehard opposition to Indian independence in the 1930s was at least partly justified by anxiety to avert the bloodshed that he rightly saw would follow a premature British withdrawal.

Of course he got some things badly wrong. His career up to 1940 is littered with reckless episodes, which allowed his enemies to disparage his judgement—above all the doomed Dardanelles campaign of 1915. (“There is some tragic flaw in Mr Churchill,” the Morning Post typically declared in 1918, “which determines him on every occasion in the wrong course.”) Roberts defends him on most of these episodes—Tonypandy, Sydney Street, Antwerp, the return to the gold standard. Frequently Roberts sets the record straight by giving the full context of quotations often used to damn Churchill—for instance on the use of poison gas in Iraq in 1921; though of course Churchill said and wrote so much on so many subjects, often contradicting himself, that it is always possible to quote selectively, and Roberts is unashamedly an advocate for the defence.

Where Roberts thinks Churchill was clearly wrong, however—for instance in allowing his visceral anti-Communism to blind him to the dangers from Mussolini and later Japan, his quixotic support for King Edward VIII’s wish to marry Wallis Simpson, or his initial willingness to put too much trust in Stalin—he says so; nor does he disguise Churchill’s grim enthusiasm for the retributive “strategic” bombing of German civilians—not just factories and military targets—until near the end of the war, when he began to get cold feet about it. Churchill’s critics will say that Roberts lets Churchill off too lightly for the bombing of Dresden (which he suggests was “signed off by Attlee in London” while Churchill was at Yalta). But he is surely right to reject the absurd allegation of genocide recently levelled at Churchill for not doing more to alleviate the Bengal famine of 1943, maintaining that the prime minister sent all the help he could without diverting critical resources from the war with Japan. Of course these and other issues will remain controversial. But Roberts is entitled to insist that overall Churchill got most of the big things right—the danger posed successively by Wilhelm II, Hitler, and the Soviet Union—when most of the political class were looking the other way or in denial; and that his crazy confidence in ultimate victory over Nazism, when he had no rational plan for how it was to be achieved, was decisive in keeping Britain in the war until Russia and America eventually came in to bring that hard-won victory about.

In focussing, as a biographer must, on the central figure of Churchill, Roberts inevitably does less than justice to some of the other players in the story—notably Lloyd George, whom he insistently presents as a false friend, constantly doing Churchill down while pretending to support him. He makes Churchill the leading figure in negotiating the Irish treaty of 1921, for instance, which he was not. Arthur Balfour famously described Churchill’s five-volume history of the Great War, The World Crisis, as “Winston’s brilliant autobiography, disguised as a history of the universe”; and there is a touch of that solipsism in this biography. But it is what I would call a heroic biography, appropriately matched to the ambition, egotism, and undoubted achievement of the life it describes. It will surely remain the outstanding Churchill biography for many years to come.

John Campbell’s books include major biographies of Margaret Thatcher, Edward Heath, and the official biography of Roy Jenkins.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.