Bulletin #83 - May 2015

Churchill et de Gaulle

April 25, 2015

Exhibition in Paris Explores Important Relationship

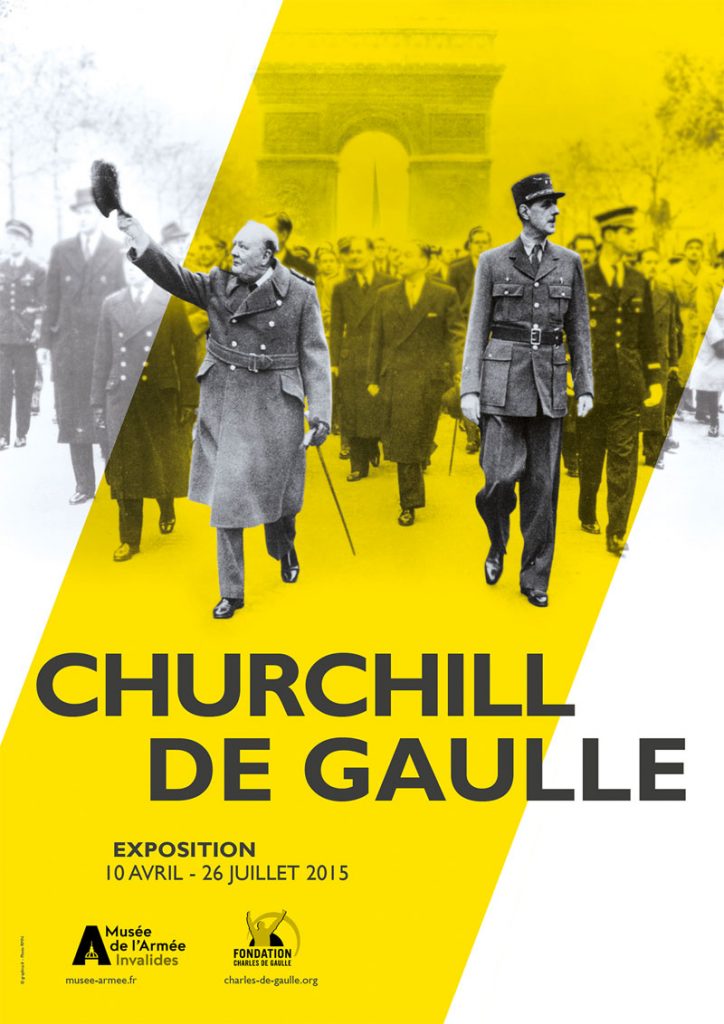

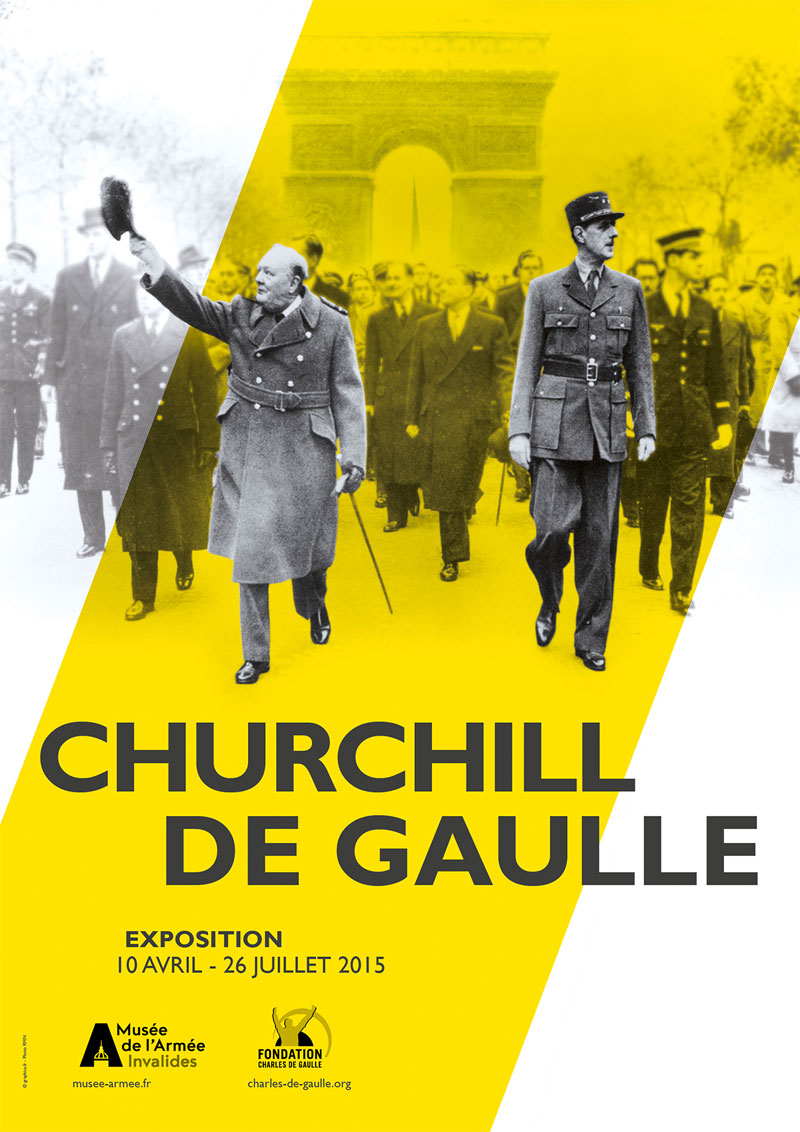

Musée de l’Armée, 10 April–26 July

Reviewed for The Churchill Centre by ANTOINE CAPET

The Hôtel des Invalides, which houses both the Musée de l’Armée (French Army Museum) and the Historial Charles de Gaulle, a large permanent display devoted to the life and action of the General, mounted a special joint Churchill–de Gaulle exhibition on the occasion both of the seventieth anniversary of the Liberation of France and the fiftieth anniversary of the death of Winston Churchill. The project was a cooperative effort, with strong British participation, notably from the Churchill Archives Centre, Cambridge, providing advice and exhibits to complement the contributions from the Fondation Charles de Gaulle and the Musée de l’Armée.

The Hôtel des Invalides, which houses both the Musée de l’Armée (French Army Museum) and the Historial Charles de Gaulle, a large permanent display devoted to the life and action of the General, mounted a special joint Churchill–de Gaulle exhibition on the occasion both of the seventieth anniversary of the Liberation of France and the fiftieth anniversary of the death of Winston Churchill. The project was a cooperative effort, with strong British participation, notably from the Churchill Archives Centre, Cambridge, providing advice and exhibits to complement the contributions from the Fondation Charles de Gaulle and the Musée de l’Armée.

As might be expected, the underlying guiding thread for the curators was the parallels, convergences and divergences between the two great leaders. Classically, we have a pictorial retrospective of their youth in the late nineteenth century, with an insistence on their easy (de Gaulle) or difficult (Churchill) relations with their parents and teachers. Their early military careers are evoked by various well-known pictures, artifacts and uniforms. But in connection with Churchill’s early political ambitions, there is a rarely seen oil portrait of 1900 by George William Fish, Winston Churchill, M.P. for Oldham. Churchill receives a fair assessment over the Gallipoli fiasco (and his later disastrous spell at the Exchequer). I was glad to see his wartime painting of “Plug Street” being given pride of place.

Captain de Gaulle, as he then was, spent most of the Great War as a prisoner of war after he was wounded and captured. His post-war fame, such as it was, was acquired not in the political field—unlike Churchill—but in the domain of theoretical military writings. Here he was on the same line as Churchill, advocating the increased use of tanks and insisting on the future role of the tactical air forces—and denouncing the futility and cowardice of the Maginot-cum-Appeasement mentality. All their publications are copiously exhibited, but I particularly liked a large wall display with a montage of Churchill’s 1920s and 1930s pot-boiler journalism, showing front pages of newspapers with such titles in bold lines as “Why not a Channel Tunnel?—by the Right Hon. Winston Churchill, MP” (remarkably prophetic, by the way, in that the accompanying drawing showed two parallel tunnels).

The really striking convergence starts with Munich in 1938: a wall text gives a passage of Churchill’s famous Commons speech of 5 October on “total unmitigated defeat,” ending with “this is only the first sip, the first foretaste of a bitter cup…” next to what de Gaulle wrote to his wife on the first: “nous boirons le calice jusqu’à la lie” (we will drink the chalice down to the dregs.)

2025 International Churchill Conference

From the tragic events of June 1940, the exhibition insists on what it calls “the war on the airwaves”—with a large number of audio documents (accessible through headsets, which obviates the cacophony sometimes heard in other museums), including short passages of Churchill in English (“The War of the Unknown Warriors”, 14 July 1940) and in French (“Dieu protège la France!”, 21 October 1940). De Gaulle is also present in these aural clips, with two remarkably contrasting speeches: one of courageous defence of the British sinking of the French fleet at Mers el-Kébir (Oran), understandably delivered with a heavy heart (BBC, 8 July 1940); the other of joy, delivered on a triumphant tone (Albert Hall, 11 June 1942), after the great feat of arms of the Free French at Bir-Hacheim. There is also a video of de Gaulle in a packed Albert Hall to celebrate what the French of the time called La fête de la Victoire, on 11 November 1942—just after El-Alamein, to which the Free French forces had modestly contributed.

With the North Africa landings in November 1942, Anglo-French quarrels reappeared with increasing frequency. The villain here is United States President Franklin Roosevelt, presented as someone who profoundly disliked de Gaulle and forced Churchill to espouse the President’s condonation of Admiral Darlan and later preference for General Giraud, de Gaulle’s only real political rival. There is an unusual and interesting document—a Déclaration in French signed by the Big Three at the Teheran Conference (1943) reaffirming their determination to crush Germany, probably meant to be posted on the walls of Occupied France by Resistance fighters. But the old Anglo-French colonial rivalry in the Levant is not glossed over. The “mésentente cordiale” and “stormy relationship” between Churchill and de Gaulle are encapsulated in a wall text with two quotations “Pauvre Churchill ! Il nous trahit, et il nous en veut d’avoir à nous trahir” (Poor Churchill! He betrays us and bears us a grudge for having to betray us—de Gaulle, 1 October 1942) and “Si vous m’obstaclerez, je vous liquiderai” (Churchill in “French” to de Gaulle, 22 January 1943).

But as in all popular films of the time, there is a happy ending, with Churchill’s triumphant welcome in Paris at de Gaulle’s side on the occasion of the fête de la Victoire, on 11 November 1944—which provides the cover of the leaflet given to visitors and the image of the official poster. In the Gaullist epic, there was no greater honour than being admitted into the Ordre de la Libération, created in 1940 and officially closed in 1946—only to be exceptionally re-opened for Churchill, who received his (exhibited) Cross from de Gaulle in person in 1958. The final section is devoted to the post-war years, with both leaders writing their memoirs and meeting the challenges of the Cold War in their own separate ways. It was a great idea to “reconstruct” the windows of their respective studies at Chartwell and Colombey-les-deux-Églises, with the superb views of the cultivated fields and distant wooded hills which they afforded.

It would be interesting to have the impressions of non-French visitors (who will not be lost since most of the captions are also given in English): though the exhibition is of course primarily intended for the French public (including schoolchildren, for whom there are special displays), I did not perceive any obvious bias in de Gaulle’s favour. As a matter of fact, I felt that Churchill’s treatment was neatly summed up by an exhibit—the cover of Paris-Match, the popular illustrated weekly, with its title on 30 January 1965, “Hommage à un Géant : Winston Churchill”.

This “tribute to a giant” is magnificently complemented by a copious catalogue, profusely illustrated and printed on heavy glossy paper, with texts (in French) by thirty-five contributors, including prominent Churchill scholars like David Cannadine, David Reynolds, François Kersaudy and Allen Packwood, who also appear on excellent explanatory videos (with sub-titles) in the rooms. In fact, potential visitors to this very attractive exhibition should allow two to three hours to take full advantage of the extensive audio and video material which usefully supplements the exhibits proper.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.