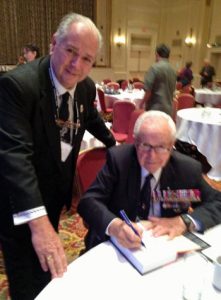

Bulletin #53 - Nov 2012

On The Road to El Alamein: Winston Churchill’s Desert Campaign

November 4, 2012

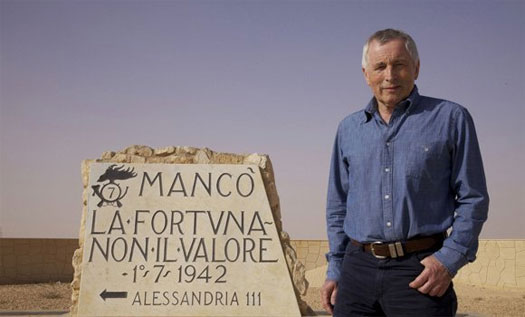

BBC Two’s Jonathan Dimbleby commemorates the 70th anniversary of the battle for North Africa.

Jonathan Dimbleby in North Africa

Jonathan Dimbleby in North Africa

By Jonathan Dimbleby

RADIO TIMES, 5 November 2012 — When Rommel was finally routed at El Alamein 70 years ago this week (4 November), Winston Churchill was so relieved that he ordered the church bells to be rung all over Britain. The prime minister had been under intense political and personal pressure to secure a decisive victory over the “Desert Fox” who, for 18 months, had persistently outsmarted the British Eighth Army on a desolate and blood-soaked battlefield.

Following the fall of Tobruk in June 1942 – a humiliation that prompted a surge of national resentment – Churchill’s critics inspired a no-confidence debate in the House of Commons. Although their target emerged virtually unscathed, the formidable Aneurin Bevan reflected a widespread feeling when he declared waspishly, “The prime minister wins debate after debate and loses battle after battle.” The jibe cut deep.

Churchill was assailed by deep gloom, fearing, as he wrote later, that he’d be driven from office “with a load of calamity on my shoulders”, while “the harvest, at last to be reaped, would have been ascribed to my belated disappearance”. He was querulous and impatient, goading his generals in the Middle East beyond all military reason. But his insatiable hunger for victory in the desert was not merely driven by an urge to save his own skin. He was a far greater man than that.

From the moment he became prime minister in May 1940, Churchill’s two overriding objectives – from which he never wavered – were to save the British Empire and to enlist the United States in the struggle to vanquish Nazism. The Middle East was critical to the fate of the Empire, a vital artery linking Britain to its possessions in Africa, India and the Far East. To lose the Middle East would not only be to imperil Britain’s global reach but the nation’s capacity to wage war effectively against Hitler as well.

Yet, following the fall of Tobruk, Rommel’s panzers seemed poised to break through the British lines at El Alamein and launch a blitzkrieg against Alexandria and Cairo – a prospect that caused panic in the Egyptian capital. When Churchill told a press conference in August, “We are determined to fight for Egypt and the Nile Valley as if it were the soil of England itself,” he was in absolute earnest.

By now, Churchill had also achieved a remarkable diplomatic coup. Against the advice of virtually all the president’s men, Roosevelt had agreed to commit US troops to fight the Germans in North Africa rather than opening a “second front” in Europe. The negotiations had been fraught with acrimony and duplicity. It’s virtually inconceivable that the US president would have agreed to this if the Eighth Army had not already been locked in combat against Rommel’s Panzer Army in Egypt and Libya. For better or worse, a desert campaign, to save an Empire that the Americans abhorred, thus came to play a pivotal role in the course of the Second World War.

The date for the Allied invasion of North Africa – Operation Torch – was set for 8 November 1942. Churchill was desperate to defeat Rommel at El Alamein before his American allies had fired a weapon in earnest against the Axis forces in Morocco and Algeria. This was partly to restore his own prestige but also to assert Britain’s status as an equal partner in the Allied struggle to destroy Nazism by demonstrating the military prowess of the British Army.

There had been severe doubts about this, not only in Washington but London as well. Writing gloomily in his diary a few months earlier, the chief of the Imperial General Staff, General Sir Alan Brooke had complained his commanding officers “lack character, imagination, drive and the power of leadership…”

In the mythology of the Second World War, all this changed when General Bernard Montgomery arrived in the desert to take command of the Eighth Army and salvage Britain’s sorry reputation.

A few days earlier, in a characteristically brutal move, Churchill had sacked General Auchinleck, the Middle East commander-in-chief, for failing to deliver the outright victory he craved. This was despite the fact that, under the Auk’s inspired generalship, the Eighth Army had just blocked Rommel’s assault on Alexandria and Cairo, ending for good the Desert Fox’s dreams of conquering Egypt and reaching the Nile.

Montgomery had another huge advantage. Rommel was, at this point, fighting “blind”. He had just lost a critical source of intelligence that, until June 1942, had allowed him to second-guess every move by the Eighth Army and respond accordingly. Much of the Desert Fox’s famed guile was in fact down to Gute Quelle (German for “good source”). It was the code word for a daily source of invaluable information provided unwittingly by Colonel Bonner Fellers, the US military attaché based in Cairo, who had unfettered access to GHQ in Cairo.

Using what the Americans believed to be an unbreakable code, Fellers had been cabling detailed and highly critical reports about the Eighth Army to his masters in Washington from the very start of hostilities in the desert. But in September 1941, an Italian secret service agent broke into a safe at the US Embassy in Rome and stole the US code. Within days, German intelligence had broken the code and Rommel knew everything that Fellers knew.

It was not until the Enigma code-breakers at Bletchley Park finally “unmasked” Fellers in June 1942, as Tobruk fell to the Germans, that Gute Quelle finally fell silent. It had been indirectly responsible for the deaths of many British soldiers. Unlike Auchinleck, this albatross of a handicap did not hang around Montgomery’s neck.

Montgomery was vainglorious and mean-spirited but his iron resolve inspired respect, even awe. When he said, “Everyone – everyone -must be imbued with the burning desire to kill Germans. Even the padres – one per weekday and two on Sundays,” no one thought he was joking. More to the point, by the time he launched the final onslaught against Rommel, he had so great a preponderance of men and weaponry that in his words, victory was a “mathematical certainty”.

This is not to detract from the importance of his achievement in a “killing match” (as he described it) that lasted 13 days, by the end of which 13,500 of his men had been killed or wounded. Nor is it to forget that he’d accomplished what Churchill required of him. Rommel’s Panzer Army was on the run, never to threaten Egypt again, four full days before the start of Operation Torch.

When Churchill declared that Montgomery’s victory at El Alamein marked “not the end, not even the beginning of the end but, possibly, the end of the beginning”, he spoke the truth, secure in the knowledge that the Middle East was no longer in danger, that his imperial strategy had prevailed, and that his position as prime minister was now unassailable. It was a triple whammy that gave him immense and lasting satisfaction.

Reader’s in the UK can watch the show on the BBC’s iPlayer here.

©Radio Times. All rights reserved.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.