Bulletin #48 - Jun 2012

Emma Soames in The Telegraph: As Churchills We’re Proud to do Our Duty

June 6, 2012

On Jubilee weekend Emma Soames reflects on the links between her family and the Crown.

By Emma Soames

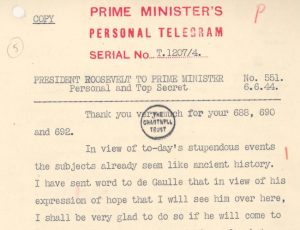

Sir Winston Churchill welcomes the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh to 10 Downing Street for dinner in April 1955 Photo: PA

Sir Winston Churchill welcomes the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh to 10 Downing Street for dinner in April 1955 Photo: PA

THE TELEGRAPH, 1 June 2012—As the young Queen Elizabeth stepped off the plane bearing her back from Kenya on the death of her father in February 1952, waiting at the bottom of the steps was my grandfather, Winston Churchill, the first of 12 prime ministers to serve under Her Majesty across the next 60 years. My family’s path has crossed with that of the Royal family many times since then, but at no time before or since has that relationship been so significant.

The scratchy television footage of that dark morning is loaded with emotion. It doesn’t just illustrate the wheels of the British constitution working smoothly as a government turns out to greet a new sovereign less than 24 hours after the death of her father, but also a prime minister in his eighties doing obeisance to his new monarch, who is a slip of a young woman, pale and determined, with a new and unprecedented burden of responsibility on her black clad shoulders.

Churchill was really deeply upset over the death of King George VI, with whom he had shared so much during the War years. Miss Portal, one of his secretaries, travelled with him to Heathrow to greet his new sovereign. “He was going to broadcast that afternoon. On the way down he dictated. He was in a flood of tears,” she told biographer Martin Gilbert.

No doubt many of his listeners were equally moved when he spoke of King George VI on the radio the following day, ending his eulogy: “I, whose youth was passed in the august, unchallenged and tranquil glories of the Victorian era, may well feel a thrill in invoking, once more, the prayer and the anthem God Save the Queen.” The following day he addressed the House of Commons: “A fair and youthful figure, Princess, wife and mother, is the heir to all our traditions and glories never greater in peacetime than now.”

My mother, Mary Soames, remembers first meeting the then Princess Elizabeth towards the end of the War at a party at Buckingham Palace given for American serving officers. “I went with my parents and the Princesses came up from Windsor for the day, ” she says.

Both Mary Churchill and the Princess joined the Auxiliary Territorial Service as soon as they were eligible: my mother served in the first mixed male and female anti-aircraft batteries, which were the last defence against aerial invasion. She started out as a Corporal and ended up a Captain, travelling to Belgium with her battery in 1945.

The Princess had to badger the King into allowing her to serve in the ATS as the authorities thought that she should not be exposed to any risks. But the Princess had other ideas and managed to get her father’s permission to do a drivers’ course, where she learnt to maintain, mend and drive large Army trucks. Most ATS members lived in camp but the Princess was only able to join on the condition that she returned to Windsor Castle at night.

Seven years later, that sombre, cold week of the Queen’s accession marked the beginning of a relationship between Churchill and the Queen which, from the start, showed mutual respect and affection, despite the fact they barely knew each other, and were almost 60 years apart in age.

On the day of the King’s death Churchill had gloomily told his private secretary Jock Colville that Princess Elizabeth was just a child, but my mother tells me: “The Queen very quickly captivated him, he fell under her spell. I think he felt early on her immense sense of duty and he looked forward to his Tuesday afternoon meetings with the young monarch.”

The relationship didn’t get off to a terrific start though. According to Jock Colville in his diaries, The Fringes of Power, during the first few weeks of her reign there was a move among some members of the Royal family to change the name of the dynasty. With some logic, Prince Philip suggested the House of Windsor become the House of Edinburgh, while from Broadlands, Lord Mountbatten unilaterally announced to a roomful of royal relatives that the House of Mountbatten should reign henceforth. Such a change could only happen with government agreement and the cabinet, led by Churchill, moved swiftly to quash both proposals. Thus we are still reigned over by the House of Windsor.

Evidently no lasting damage to their relationship was done as, just three months later, the Queen invited her Prime Minister to become a Knight of the Garter, one of the oldest orders of chivalry and one of the few in her personal gift. King George VI had offered it to Churchill in 1945 when he lost the General Election but he had turned it down. Indeed, he was reported to have said: “What would I want with the Garter when I’ve just got the boot?”

Back then Churchill was raw from his defeat but later, according to my mother, he was deeply gratified to receive the honour at the hands of his new sovereign. Among the many letters of congratulation Churchill received was one from a fishmonger from Blackpool who sent – separately one hopes – “the best halibut I could find”.

On April 24 1952, the Queen invested my grandfather with the Order at Windsor Castle and the following year, on the day of the Coronation, he left No 10 Downing street dressed in his Garter robes, worn over the uniform of the Warden of the Cinque Ports. He was, of course, accompanied by my grandmother, Clementine, who looked sensational in a borrowed tiara and the petunia satin robe of the Order of the British Empire.

Aged barely four, I was photographed with my gloriously attired grandparents on the steps of No 10 with my knobbly knees and short white socks. Apparently I watched the procession with my brother from the windows of Whitehall but sadly I have no memory of this other than the photographic evidence.

For adults, it was a summer of great celebrations and London sparkled with parties – by all accounts, tiaras, dress uniforms and decorations were worn almost every night. In the week before the Coronation, there was a Coronation Ball at the Albert Hall, preceded by a splendid dinner at No 10 Downing Street hosted by the Churchills. This was followed by the Household Brigade’s Ball at Hampton Court, where the Queen looked radiant as she took to the dance floor with her handsome husband.

The Churchills also hosted a dinner for the Queen at Lancaster House three days after the Coronation for all the visiting heads of state. According to Jacqueline Bouvier (later Mrs Kennedy) who was reporting for a Washington paper, Claridge’s was full of deposed royalty who all had to get their hair done at 3am on Coronation day in order to get to their seats in Westminster Abbey by 6.30am, wearing their tiaras.

After the giddy excitement of the coronation year, the working relationship between Churchill and the Queen continued until he retired in 1955. The night before his resignation, the Queen attended a dinner at No 10 Downing Street where, in full regalia, she was greeted by her Prime Minister in his last 24 hours in office. Proposing the Queen’s health, Winston reminded the 50-odd guests that it was a toast he’d enjoyed drinking during the days when he was a cavalry subaltern in the reign of Her Majesty’s great-great-grandmother, Queen Victoria. He also spoke of “the wise and kindly way of life of which Your Majesty is the young and gleaming champion”. When he sat down the Queen rose and charmingly and simply proposed the health of “My Prime Minister”.

After his retirement he inevitably saw less of the Queen, but they kept in touch on the matter of racehorses; most memorably when the Queen’s horse roundly beat Churchill’s famous Colonist II. Churchill fired off a generous telegram of congratulation to which she immediately responded saying she was sorry he was not in closer attendance.

Seven years before his death the Queen let it be known that she wished him to have a state funeral and a lying in state – which would make him the first commoner to be honoured in this way since the Duke of Wellington. According to my mother, my grandfather was deeply touched and gratified by the gesture “from the sovereign whose family he had so long served, and for whose person he had such a great regard and affection”. His family, of course, thought the same but none of us wished to dwell on a future without him.

My mother, despite knowing the Queen for nearly her whole life, has never been part of her close circle. But more than 50 years after her father was made a Knight, the Queen invited her to become a Lady Companion of the Garter. When she was invested at Buckingham Palace in 2005, the Queen made a point of telling her that it was Churchill’s collar she was wearing as part of the Garter insignia. It was a proud yet humbling moment for my mother that will stay with her forever. “I am bereft of words to convey my gratitude which is indeed heartfelt,” she wrote after the investiture.

And so the paths of the Royal family and the Churchills crossed again, and they are still doing so. My brother Nicholas served as an Equerry to the Prince of Wales shortly after he left Oxford, and six years ago Earl Peel – who is married to my sister Charlotte – became Lord Chancellor, the senior official in the Royal Household. When asked, we will always follow in my grandfather’s footsteps and do our bit. But I’m almost certain there will be no more State Funerals – at least for this generation.

Read the entire article at The Telepgraph

The Telegraph © All rights reserved.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.