Bulletin #30 - Dec 2010

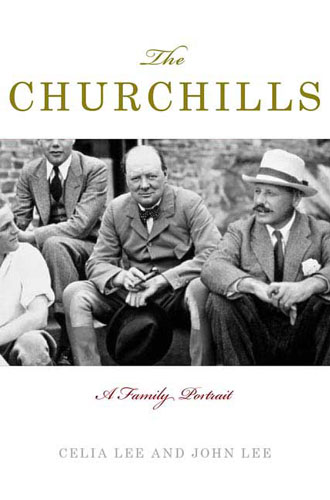

“The Churchills – A Family Portrait” by Celia Lee and John Lee

November 17, 2010

An excerpt of the recently released new work – Part 2 of 2

The Churchill family motto on their coat of arms, “Faithful But Unfortunate,” was an apt description of Winston’s romances to date. The thought of his political career and a life in the public eye, together with his lack of fortune, and his adventures in war, was too daunting a prospect for most young ladies to whom Winston proposed. He and Pamela, now the Countess of Lytton, were on the best of terms.

…

But a new love was about to enter Winston’s life. He had met Clementine Hozier again in March 1908 when her great-aunt, Lady St. Helier, gave a dinner party at her London home. Clemmie was the daughter of Sir Henry Montague Hozier and Lady Blanche née Airlie. Clemmie was also of noble and ancient lineage on her mother’s side as her grandparents were the Earl and Countess of Airlie who lived at Castle Airlie in Scotland. Henry had died in 1907, but Clemmie hardly knew her father. Her parents never got on and had lived apart from her childhood.

Be that as it may, at Lady St. Helier’s dinner party, Winston, having turned up late, seated himself in the chair next to Clemmie with whom he had been partnered. On this occasion, he finally got up the courage to engage her in conversation. Now aged twenty-two, Clemmie had matured into a radiant, beautiful redhead, with a fine complexion, and sparkling, green-hazel eyes. She possessed a natural charm and great intelligence, having been an excellent academic at school. Clemmie had been head girl at Berkhampstead School, where she excelled in French and German. When she left school, her mother was so hard up financially that Clemmie made a small living of her own, giving French lessons for payment. A firm Liberal, she had witnessed Winston in action in the Commons and was impressed by his speeches and admired him. He was taken by her beauty, charm, and intelligence, and they had something in common in their interest in politics. Clemmie was a no-nonsense type of girl, with her feet firmly on the ground, and was, without a doubt, the best girl in the world for Winston. Winston spent the rest of the evening in Clemmie’s company. He asked her if she had read his recent biography of his father, and when she told him she had not, he offered to send her a copy, but true to Winston, he forgot to do so.

Winston’s elevated political status (as President of the Board of Trade) and the salary that went with a cabinet minister’s post meant that he had enough money on which to marry and provide for a wife. He asked his mother to invite Clemmie to spend the weekend of April 11 at Salisbury Hall. Their signatures appear in Jennie’s house book. Clemmie wrote to Jennie, on Monday April 13, thanking her for the weekend:

At this moment your whole mind must be filled with joy & triumph for Mr. Churchill, but you were so kind to me that you made me feel as if I had known you always. I feel no one can know him, even as little as I do, without being dominated by his charm and brilliancy.

Meanwhile, Jennie did everything she could to further the relationship, and when Clemmie returned, she was again invited to Salisbury Hall. On May 28 her signature is recorded in Jennie’s house book.

…

Winston’s life as a cabinet minister was packed with engagements. In accordance with the social restrictions of the times, Clemmie could not be seen alone with Winston in public. Blanche was so badly off financially she could not pay for a maid for her daughter. Clemmie was therefore reliant on her mother or Jennie to escort her when in company with Winston. Consequently, the young couple only managed to see each other at intervals over the intervening weeks…

Winston wrote to Clemmie, on August 8, inviting her to Blenheim Palace. Despite being the granddaughter of an earl and countess, she felt shy about going to the overpowering ancestral Marlborough home. Her family had little money, and she had so few clothes, she was down to her last starched dress. Her mother could not accompany her, so in the afternoon of August 10, Jennie went with Clemmie and they spent the night there. On the morning of August 11, she presented herself at breakfast on time, but Winston did not appear. She nearly went home. Sunny had to send up a note to get Winston out of bed.

In the afternoon, Winston took Clemmie for a walk in the garden, but the unpredictable British weather put a damper on his romantic plan to show her the lovely gardens and the roses. The heavens suddenly opened when a torrential rainstorm blew up, and they had to take refuge in the ornamental Greek temple overlooking the lake. Winston dithered and dithered, and did not pop the question, and Clemmie saw an insect crawling across the stone floor toward a crack. She said to herself that if he did not propose before the beetle reached the crack, he never would. But Winston’s declared his love for her, and asked her to marry him, and she accepted.14

For once in Winston’s life everything was going right for him. The betrothal was supposed to be kept a secret for the moment, but Winston was so excited that he got completely carried away and ran across the lawn and told the others the news. He wrote a letter to Clemmie’s mother, on August 12, telling her he felt Clemmie’s love would give him the strength to take on the “great and sacred responsibility” of giving her the happiness “worthy of her beauty and her virtues.”

…Clemmie’s grandmother, the Countess of Airlie, wrote to both Jennie and Winston of her joy at the match. To Winston she said: “A good son is a good husband.”17 It was undoubtedly one of the best compliments anyone had ever paid him.

The official announcement of the engagement appeared in The Times, on Saturday, August 15. King Edward VII telegraphed his good wishes from Marienbad. In the midst of trying to find a wedding dress, Clemmie wrote to Winston, on August 22, “My darling . . . I feel there is no room for anyone but you in my heart-you fill every corner.” And later: “how I have lived 23 years without you. Everything that happened before about 5 months ago seems unreal.” Winston replied: “There are no words . . . to convey to you the feelings of love & joy by which my being is possessed. May God who has given me so much more than I ever knew how to ask keep you safe & sound.”18

On the wedding day, September 12, 1908, the bride and groom passed through the City of London, and were cheered by large crowds assembled in Parliament Square. The wedding took place at 2:00 P.M., in St. Margaret’s Church, Westminster, the church of the House of Commons. It overflowed with family, friends, and political dignitaries. Clemmie was given away by her brother, William, (Bill), who was a sublieutenant in the Royal Navy. She was a dream of loveliness, wearing a shimmering ivory satin gown, with flowing veil of soft white tulle, held in place by a coronet of white American orange blossoms… Her only jewels were diamond earrings, a gift from Winston. Winston’s old headmaster from Harrow Public School, now Bishop Welldon, Dean of Manchester, gave a most appropriate address:

There must be in the statesman’s life many times when he depends upon the love, the insight, the penetrating sympathy, and devotion of his wife. The influence which the wives of our statesmen have exercised for good upon their husbands’ lives is an unwritten chapter of English history, too sacred perhaps to be written in full.19

Winston’s best man was a great friend of his, Lord Hugh Cecil, Conservative member for Greenwich in South East London.20 The only flaw in the otherwise immaculate turnout was Winston’s suit, reported by the Tailor and Cutter as having something of a “flung together at the last minute” appearance about it, “neither fish, flesh, nor fowl . . . one of the greatest failures as a wedding garment we have ever seen, giving the wearer a sort of glorified coachman appearance.”

…

The wedding reception, a modest affair for family and a few friends, was held at the house of Clemmie’s aunt, Lady St. Hilier, in Portland Place, London. The young couple left immediately afterward for Woodstock in Oxfordshire to begin the first two nights of their honeymoon in the splendid surroundings of Blenheim Palace… When Winston and Clemmie arrived at Woodstock, there was another crowd waiting to cheer them, and the bells of the church of St. Mary Magdalene rang out.

Winston wrote to his mother on September 13 of his wedded bliss, and the marvelous honeymoon they were looking forward to in Italy for two weeks. Jennie would soon be a grandmother twice over.

Excerpted from The Churchills – A Family Portrait by Celia Lee and John Lee. Copyright © 2010 by the author and reprinted by permission of Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Ltd. We would like to thank Senior Publicist, Lauren Dwyer for her help in making these arrangements. Photographs are by kind permission of Mrs. Peregrine (Yvonne) Spencer Churchill.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.