Writings

A Comprehensive Historiography and Annotated Bibliography

Winston Churchill, Parliament Square, London © Sue Lowry & Magellan PR

October 17, 2008

Winston S. Churchill, 1874-1965: A Comprehensive Historiography and Annotated Bibliography, by Eugene L. Rasor. Bibliographies of World Leaders series, No. 6. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 706 pages, published at $115.

Reviewed by Christopher M. Bell

Dr. Bell is a naval historian and postdoctoral fellow at Simon Fraser University and a contributor to Finest Hour. He is presently teaching at the Naval War College in Newport, R.I.

At first glance this is a very impressive book. Eugene Rasor has compiled a series of historiographical essays and an annotated bibliography covering over three thousand works by and about Winston Churchill. Handled well, this might be a formidable achievement, and the author deserves credit for taking on such a huge task. Unfortunately, the final product is marred by so many errors, omissions, and inconsistencies that its merits are frequently overshadowed.

This is a very different type of work from Woods’s bibliography. It is not a descriptive bibliography, which collectors might anticipate from the title. The bibliographical portion of the book consists of a single long catalogue of published works listed alphabetically by author, and then arranged alphabetically, rather than chronologically, by title. Churchill’s own writings, including both books and pamphlets, are listed together with works about Churchill, and account for a meagre twenty-seven of the book’s 3099 entries.

2024 International Churchill Conference

All of these works are noted and discussed in the historiographical essays which comprise slightly more than half of the volume. This section is undoubtedly the book’s strong point, although the quality of the essays varies considerably. Individual chapters cover areas such as Reference Publications, Biographies, World Wars I and II, the Cold War, Major Controversies, and the Anglo-American ‘Special Relationship.’ Each one provides a commentary on relevant works by and about Churchill, together with historical background and notes on a wide range of books and articles which do not focus specifically on Churchill. The reader interested in Churchill’s political career, for example, will find not only an overview of the key works on this subject, but also a guide to surveys of modern British politics, histories of the major political parties, and biographies of key figures.

This attempt to provide ‘context’ will be welcome to many readers, but may frustrate others, particularly as the author is prone to wander into areas of only peripheral interest to Churchill. There are, for example, lengthy sections on topics such as the spy scare in Britain before the First World War, the German navy, and the ‘great game’ in central Asia during the 19th century, all of which contain numerous works which are clearly out of place in this book (e.g., The Beginning of the Great Game in Asia, 1828-1834). Even when a topic does have a clear connection to Churchill, Rasor still rounds out many of his historiographical essays with irrelevant sources. His section on the loss of the Lusitania, for example, notes items such as a reprint of a 1907 pamphlet describing the liner and an article by the nautical archaeologist-explorer who located its wreck.

Readers may be disappointed that some worthwhile topics are not given separate historiographical treatment, such as Churchill and the Dominions (particularly Australia and Canada) and the loss of Hong Kong in 1941.

There are other problems stemming from the organisation of the book’s chapters. A certain amount of overlapping is to be expected, but this problem is not always handled well. Rasor seems reluctant to list an item more than once, and important works are often not found under all of the relevent headings. Those dipping into the book to find out about Churchill and naval matters during the First World War, for example, will have to look under “the Admiralty” and “naval leaders” in chapter 10, “World War I” in chapter 6, “Gallipoli” in chapter 13, and The World Crisis in chapter 4 to be sure they have not missed anything important. Similarly, a section on Churchill in cartoons omits Churchill: A Cartoon Biography and Poy’s Churchill, both of which are found elsewhere, in “biographies with special effects,” which they are not. Warren Kimball’s Forged in War and Churchill and Roosevelt: The Complete Correspondence do not appear in chapter 12 (Churchill and Other Leaders) under the heading “Franklin D. Roosevelt,” but will be found two chapters later (Churchill and the Special Relationship) under “Winston S. Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt”! Many of these anomalies could have been avoided by better cross-referencing. Perhaps inevitably, some significant works do not appear at all, such as Lady Soames’s Winston Churchill: His Life as a Painter.

There are few important books or articles about Churchill which are missing from this book entirely, but the historiographical section suffers from two other serious problems. First, the author seldom notes articles which appear in anthologies. The reader interested in Churchill and the navy, for example, will not be alerted to articles with that title by Admiral Sir William James (in Churchill by His Contemporaries), Admiral of the Fleet Lord Fraser (in Marchant’s Servant of Crown and Commonwealth), and Richard Ollard (in Louis and Blake’s Churchill), or other relevant pieces like Jon Sumida’s excellent “Churchill and British Sea Power, 1908-1929” in R. A. C. Parker’s Churchill: Studies in Statesmanship. Dozens of articles by notable experts on different aspects of Churchill’s life and career are therefore absent from the historiographical essays, even though the collections in which they appear are noted in the bibliography at the back of the book. Unfortunately, Rasor does not even list the articles which comprise these anthologies.

The second problem is the treatment of Churchill’s own works, which receive a superficial and incomplete survey in a chapter on Churchill as Journalist, Author, and Historian. Inexplicably, some important books are absent altogether, including For Free Trade, Mr Brodrick’s Army, The People’s Rights, Step by Step, the last three volumes of postwar speeches, and the four-volume Collected Essays. Three speech pamphlets are noted, but over a hundred others are absent. Furthermore, little effort has been made to incorporate Churchill’s writings, and particularly his many articles, into the later historiographical essays.

Rasor displays remarkably little familiarity with the wide range of subjects Churchill wrote on. Thus, the entry for Churchill’s visit to Cuba in 1895 does not note that Churchill published a series of dispatches about his experiences in The Daily Graphic, nor does it mention where these pieces have been reprinted. The section on King George V fails to report the seven articles on his reign by Churchill, originally published in The Evening Standard and reprinted in the Collected Essays, or the script he wrote for a proposed film about the monarch (printed in the Official Biography’s Companion Volumes). There are literally dozens of articles by Churchill on topics such as Antwerp, Gallipoli, Jutland, Hitler, and Roosevelt, which are seldom noted individually in the volume, even when they are readily available in collections such as Thoughts and Adventures and Great Contemporaries.

The bibliography at the end of the book has problems of its own. The annotations are seldom more than a summary of comments from the historiographical section. A handful are detailed, opinionated and incisive, but most are short and cryptic, sometimes to the point of being incomprehensible. Few are really helpful, and some are so brief as to be completely useless. Several PhD. dissertations, for example, are described simply as ‘scholarly studies,’ while a work like Haldane of Cloan: His Life and Times is described as ‘A biography.’ The reader will often be left wondering whether Rasor has actually read some of the works he purports to describe.

Once again, the author is weakest when it comes to Churchill’s own writings. He correctly notes that this is a large subject, but is wrong to suggest that he presents ‘an adequate summary’ (319). He does not appear to have consulted Richard Langworth’s Connoisseur’s Guide, which would have corrected many of his mistakes about Churchill’s books; and he definitely did not consult Ronald Cohen’s bibliography of Churchill’s writings, because this work has not appeared, even though Rasor shows a 1998 publication date for it, and even provides a page count!

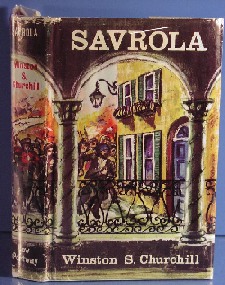

The entries for Churchill’s books are nothing short of a bibliographic disaster. Rasor lists the publishers for each work and the dates of publication separately; and, to make matters worse, these lists are frequently incomplete and inaccurate. Abridged and revised editions of a work are not always noted, let alone matched up to publishers or dates. Only two of the eleven publishers of Great Contemporaries are noted, for example. The list of dates for this work is also incomplete, with no mention at all of the bibliographically significant revised edition of 1938. Similarly, the entry for The World Crisis does not inform the reader that later editions contain additional new material on the Battle of the Marne, or that some editions are heavily abridged. Rasor also fails to note that Churchill contributed new introductions to later editions of works such as Lord Randolph Churchill and Savrola.

There are important errors or omissions for nearly every one of Churchill’s books. The War Speeches, for example, does not exist in a seven-volume edition, as Rasor claims. There are, however, seven individual volumes containing Churchill’s war speeches, each published separately and with its own title, only two of which are mentioned here. Nor is there either a six- or a two-volume edition of this work–only a three-volume edition (which is noted) and a one-volume edition (which is not).

Contrary to Rasor, Cassell did not publish any edition of the Collected Works, an extension of which, the four- volume Collected Essays, is a distinct and more important collection and should be listed separately. Similarly, The Churchill Center has never published an edition of The Sinews of Peace, a collection of postwar speeches, although it has published the 1946 “Sinews of Peace” speech in pamphlet form. The list of careless mistakes is a long one.

The author also makes the curious decision to use only the first word of a publisher’s name throughout the bibliography (eg., “Simon” for Simon and Schuster). In the event, this practice is only haphazardly followed. Thornton Butterworth, for example, is sometimes “Thornton”, sometimes “Butterworth”; Frank Cass is, sensibly, “Cass,” but Books for Libraries is usually not abbreviated at all, although it is noted at least once as ‘Books for Librarians’ and once as ‘Libaries’ (sic). To compound this problem, many of the abbreviations used in the bibliographic section do not appear in the list of abbreviations at the beginning of the book. All of this can only create difficulties for anyone attempting to locate copies of the works described in this book.

The bibliography suffers from other inconsistencies. Only a few translations of English-language works into other languages are noted, but when they do appear they are given their own separate entries. Only four or five of the hundreds of articles and reviews published in Finest Hour are singled out for inclusion. The author also provides entries for a handful of paintings, photos, and statues, but the criteria for selection are once again unclear. The work as a whole shows many signs of being put together in a hurry: the number of typographical errors is truly alarming, and the author’s writing is often stilted and confusing.

Despite its many shortcomings, the book can only be condemned outright for its essentially valueless treatment of works by Churchill. The rest of the volume contains a wealth of useful information for scholars, students and Churchill enthusiasts, even if it must be used with caution. It is a frustrating, confusing, and sometimes misleading work, but for the time being it is the best reference book available on the vast literature about Winston Churchill. One must hope, however, that it will not hold this distinction very long.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.