StoryElement

Churchill and Education by David Cannadine

Winston Churchill, Parliament Square, London © Sue Lowry & Magellan PR

January 1, 1970

When Winston Churchill was born in 1874, W. E. Forster’s Education Act, which is widely regarded as the beginning of modern mass education in this country, had only been on the statute book for four years. By the time of his death, in 1965, the Robbins Report had advocated a significant expansion in higher education, while Harold Wilson’s Labour Government was carrying through a revolution in secondary education, aiming to supersede grammar schools with comprehensives. To a greater extent than ever before, education was thus a major political issue during Churchill’s lifetime: Who should receive it? To what level and to what age? How should individual performances be assessed? And what part should the state play in providing and funding education? Perhaps because of his own unhappy experiences as a schoolboy, Churchill himself was never much interested in these questions.

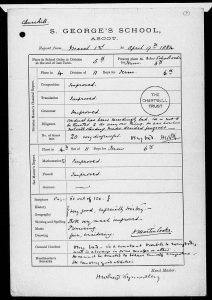

Both at his preparatory schools and at Harrow, he resented head-masterly authority, disliked rote learning, hated examinations, and was generally regarded as a ‘troublesome boy’; and while he may have exaggerated his scholarly shortcomings in the pages of My Early Life, he was deemed insufficiently clever to go on to university, but had to make do with the Royal Military College at Sandhurst instead. The result, as R. A. Butler would later note, was that Churchill’s interest in education was ‘short, intermittent and decidedly idiosyncratic’. While Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1924 to 1929, he did all he could to cut spending on state schools in the pursuit of retrenchment and economy, and the President of the Board of Education, Lord Eustace Percy, was convinced he was taking belated revenge for his own miserable schooldays.

For much of the Second World War, R. A. Butler was in charge of education: but Churchill did not regard the post as ‘a central job’, he had moved Butler there to get him out of the Foreign Office where he was deemed too much of an appeaser, and on offering him the appointment, Churchill informed Butler that the purpose of mass education was to ‘tell the children that Wolfe won Quebec’. Nor did his opinions on the subject mellow with age: as peacetime premier between 1951 and 1955, Churchill paid scant attention to Florence Horsbrugh, the Minister of Education, whom he regarded as a weak and marginal figure, and thus an appropriate person for the job, and he did not initially give her a seat in the Cabinet; while his private opinion was that the newly-raised school-leaving age should be lowered back to fourteen.

Yet there was one area of education which did become important in Churchill’s life, and that was universities, beginning with his unexpected appointment as Chancellor of Bristol in 1929. Churchill always regretted that he had never been able to study for a degree, and he constantly alluded to this during the speeches he made at Bristol in the 1930s. For the fifteen years from 1940, he was showered with honorary degrees in Britain, in Europe and in the United States, and in the speeches he gave on such occasions, he spoke frequently and eloquently in defence of universities and in praise of the benefits, both individual and collective, of higher education. Indeed, no British prime minister has ever been given, or gladly taken, so many opportunities to celebrate academic learning as Churchill did.

2024 International Churchill Conference

But he also appreciated that university and college campuses were the ideal setting to make broad-ranging speeches on the state of the world, most famously at Harvard (on Anglo-American amity), at Fulton (on the ‘iron curtain’), at Zurich (on European unity) and at MIT (on twentieth century science). It was, then, appropriate that the national memorial to him should be the establishment of Churchill College, Cambridge, which Churchill hoped might emulate MIT, training scientists and technologists who would help keep Britain at the forefront of world affairs. Later prime ministers, from Eden to Macmillan, Wilson to Thatcher, may all have attended Oxford, and they were chancellors of British universities; but only Churchill is commemorated with an Oxbridge college named after him. Not bad going for someone who once described himself as ‘an uneducated man’.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.