Finest Hour 171

Books, Arts & Curiosities – Churchill and the Isle of Wight

March 20, 2016

Finest Hour 171, Winter 2016

Page 48

Review by Anne Sebba

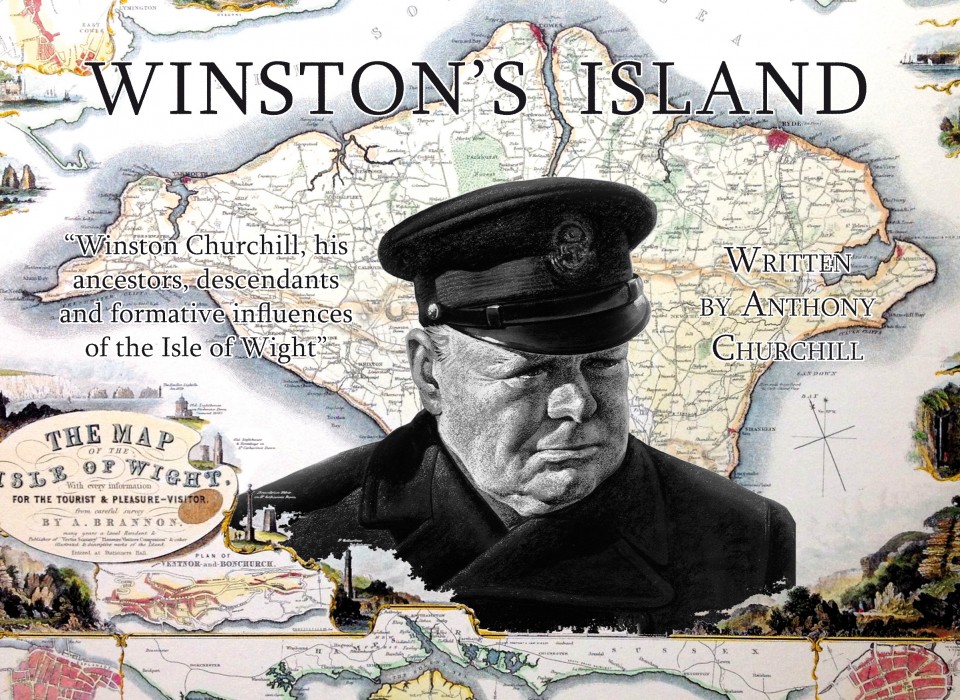

Anthony Churchill, Winston’s Island, Chale, Isle of Wight: Cross Publishing, 2015, 112 pages, £40.00.

ISBN 978-1873295540

To purchase, go to www.winstonsisland.co.uk

What’s in a name? Anthony Churchill describes himself as “a very minor” Churchill on his father’s side through the Dorset branch of the family, and “a very minor” Spencer on his mother’s. He had, he insists, never bothered too much about his famous family name until he retired some years ago and put down roots on the Isle of Wight, where he kept discovering snippets of history linking his illustrious ancestor to the island. As an ocean racer who had sailed with Ted Heath on all his Morning Cloud yachts, winning the Sydney Hobart Yacht Race as navigator strategist, he was frequently in Cowes and noted that Winston Churchill’s parents had met and fallen in love there in 1873 after an intense three-day romance. When he realised that the 140th anniversary of that meeting would fall in 2013, he set about organising a gala dinner on the island, inviting as many of the family as he could muster. After that he decided there had to be a book recording all the links.

What’s in a name? Anthony Churchill describes himself as “a very minor” Churchill on his father’s side through the Dorset branch of the family, and “a very minor” Spencer on his mother’s. He had, he insists, never bothered too much about his famous family name until he retired some years ago and put down roots on the Isle of Wight, where he kept discovering snippets of history linking his illustrious ancestor to the island. As an ocean racer who had sailed with Ted Heath on all his Morning Cloud yachts, winning the Sydney Hobart Yacht Race as navigator strategist, he was frequently in Cowes and noted that Winston Churchill’s parents had met and fallen in love there in 1873 after an intense three-day romance. When he realised that the 140th anniversary of that meeting would fall in 2013, he set about organising a gala dinner on the island, inviting as many of the family as he could muster. After that he decided there had to be a book recording all the links.

Now in his ninth decade and living on the south side of the island at Ventnor—he prefers the rougher seas that side—Anthony Churchill has lovingly assembled a profusely-illustrated volume detailing every connection between Winston and the island, starting with ancestors on both sides, Jeromes as well as Churchills. He retells the story of John Churchill, later the first Duke of Marlborough, who in 1679, thanks to his friendship with the Governor, Sir Robert Holmes, accepted a parliamentary seat at Newtown, then capital of the island and largely in ruins following a devastating series of French attacks. Anthony Churchill also discusses the likelihood that the Jeromes, Winston’s mother’s family, were originally Isle of Wight Protestants trading with France rather than French Huguenots who had fled to the isle. Either way, Timothy Jerome, possibly with two brothers John and Stephen, sailed to America in about 1719, probably with the grant of a monopoly in salt manufacturing in Connecticut. Churchill believes that Leonard Jerome’s subsequent attraction to the Isle of Wight owed something to his knowledge that his ancestors had originated from there.

In the late nineteenth century the island was important for Winston and his younger brother Jack as the two boys often spent school holidays there with their devoted nanny, Mrs Everest, called by Winston “Woom” from babyhood onwards. Mrs Everest’s brother in law, John Balaam, her sister’s husband, was chief warden at Parkhurst Prison, having worked there for nearly thirty years, and it is he who is credited with having fired Winston’s young imagination on these holidays. John Balaam often took the schoolboy for long walks over the downs, all the while telling him gripping and frightening stories of mutinies in the prisons and how he had been attacked and injured on several occasions by the convicts.

2025 International Churchill Conference

Lord Randolph, worried about whether Everest’s friends were respectable people or whether his sons risked catching scarlet fever or something similar if they stayed in such places, was reassured by Jennie, who found that getting the boys off her hands was a relief so she could concentrate on entertaining for her husband. But Jennie always loved

Cowes—it was a happy reminder for her of the place where, aged nineteen, she had fallen in love with Randolph, and she returned there regularly.

This is an unusual mix of a book; part guide book, part history or biography, and part glossy magazine pages. There is a story of Winston, a noted opponent of women’s suffrage, having a run-in with some suffragettes on the island when he visited in 1910 as Liberal Home Secretary and made four speeches there. In Yarmouth he was chased by suffragettes onto a special boat returning him to the mainland. There are also some fascinating pages devoted to the geological formation of the island, including the “almost unknown” deep gash known as Churchill Chine.

But for me the best part was an account of the gala dinner entertainment where two of Winston’s great grandchildren, appropriately Randolph Churchill and his sister Jennie, recounted the events of 1873, including a letter in which the young Lord Randolph reassured his parents that with Jennie at his side he is sure he can make something of his life and become “all, and perhaps more, than you ever wished and hoped for me.”

It is a beautifully produced book, richly illustrated with marble endpapers and gilded on all three edges with some fascinating details certain to appeal to all those who collect Churchilliana. Anthony Churchill insists that he decided to write this book for a better knowledge of Winston, but also from a sense of curiosity “and a decision that if I did not write it, nobody else would.” How lucky he did.

Anne Sebba is the author of Jennie Churchill, Winston’s American Mother. Her latest book, Les Parisiennes: How the Women of Paris Lived, Loved and Died under Nazi Occupation, will be published in the UK and the US in 2016.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.