Bulletin #206 — Jul 2025

The Führerbunker

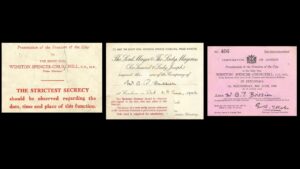

Churchill sits on Hitler's chair outside the ruined bunker; Image: Wikimedia Commons

June 27, 2025

Churchill Tours Hitler’s Final Lair

By FRED GLUECKSTEIN

Prior to the Potsdam Conference eighty years ago this month with Russian leader Joseph Stalin and American President Harry S. Truman, Prime Minister Winston Churchill arrived in Berlin on 16 July and toured the ruins of the German capital in the company of his daughter Mary and Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden. Driven to the Tiergarten, they first examined the ruins of the Reichstag. Afterwards, they toured what remained of Adolf Hitler’s Chancellery, which had been the site of the Führer’s official residence, office, and bunker.

In the last phase of the tour, Churchill’s Russian guides led the party to Hitler’s concrete underground air-raid shelter. A flashlight lit their way. Stagnant water, however, made the steps slippery. For Churchill, unsteady on his feet, the steps were precarious. Aided by his gold-headed walking stick, he made his way down the dark, wet steps, but—with two flights still to go—he thought better of it and slowly began climbing back to the surface.

“Churchill emerged from Hitler’s bunker under his own power,” wrote historian Barbara Leaming, “but when at last he reached the top of the stairs and passed through the door of a concrete blockhouse into the daylight, his hulking frame appeared so shaky and depleted that a Russian soldier guarding the entrance reached out a hand to steady him….The Chancellery Garden was a chaos of shattered glass, pieces of timber, tangled metal, and abandoned fire hoses. Craters from Russian shells pocked the ground. In one of those craters, Hitler and his wife has supposedly been buried after Nazi officers burned their corpses. The rusted cans for the gasoline still lay nearby. Russians pointed out the spot where the bodies had been incinerated. Churchill paused briefly before turning away in disgust.”

2025 International Churchill Conference

Churchill rested on a beat-up chair that had been propped against a bullet-riddled wall. The Russians said the chair had been Hitler’s. “Gingerly perched on the front edge of the seat,” Leaming continued, Churchill “mopped his forehead with a handkerchief in the withering heat as he chewed on a cigar. When at length his daughter and the others came out of the bunker, Churchill was visibly eager to leave.”

Undoubtedly, Churchill had many thoughts about the war as he viewed the once-proud headquarters of his vanquished enemy. Later, he wrote that history would have been better served had the Führer not committed suicide: “The course Hitler had taken was much more convenient for us than the one I feared. At any time in the last few months of the war he could have flown to England and surrendered himself, saying, ‘Do what you will with me, but spare my misguided people.’”

“I have no doubt that he would have shared the fate of the Nuremberg criminals,” Churchill mused. “The moral principles of modern civilisation seem to prescribe that the leaders of a nation defeated in war shall be put to death by the victors. This will certainly stir them to fight to the bitter end in any future war, and no matter how many lives are needlessly sacrificed it costs them no more. It is the masses of the people who have so little to say about the starting or ending of wars who pay the additional cost.”

Churchill’s tour of the ruined Chancellery was a personal triumph, but his empathy for humanity meant that the visit gave him no pleasure.

Fred Glueckstein is author of Sir Winston Churchill: Published Articles of a Churchillian (2021). This article is adapted from a longer version appearing in the next issue of Finest Hour, which is about the eightieth anniversary of the end of the Second World War.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.

Oops! We could not locate your form.

Privacy