Finest Hour 201

The Double Interpreter

September 25, 2024

Maisky between Churchill and Stalin

Finest Hour 201, First Quarter 2023

Page 21

By David Reynolds

David Reynolds is Emeritus Professor of International History at Cambridge University, a Fellow of the British Academy, and a member of the ICS Board of Academic Advisers. With Vladimir Pechatnov, he published The Kremlin Letters: Stalin’s Wartime Correspondence with Churchill and Roosevelt (Yale University Press, 2018), which was awarded the Link-Kuehl Prize by the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations.

Throughout the Second World War, Winston Churchill held two views of the Soviet Union (USSR) in an uneasy tension. On the one hand, at the level of realpolitik, he was sure that Britain and Russia shared a clear interest in containing and defeating Hitler. On the other hand, he abhorred Bolshevik ideology and was determined to stop it spreading across Europe. That is why he had tried to strangle the Revolution in its cradle after 1917, damning what he called “the foul baboonery of Bolshevism.”1

After Hitler broke the Nazi Soviet Pact in June 1941 and turned on the Soviet Union, Churchill found the key to this new, if unholy, alliance in the shadowy figure inside the walls of the Kremlin. Fascinated by getting up close and personal with other leaders—Franklin Roosevelt above all—he became determined to build some kind of personal relationship with Josef Stalin. And the broker was Ivan Mikhailovich Maisky (1884 1975), who operated as a kind of “double interpreter” between the prickly pair: trying to help Stalin to understand Churchill and Churchill to understand Stalin.2

This essay draws on The Kremlin Letters—an edition, with commentary, of the wartime correspondence between Stalin, Churchill, and Roosevelt, which I published in 2018 in collaboration with Professor Vladimir Pechatnov in Moscow.3 It also uses the superb edition of Ambassador Maisky’s wartime diaries prepared by Professor Gabriel Gorodetsky. This offers insights into the Prime Minister that are not to be found in Churchill’s voluminous papers or in the Stalin archives.4

2025 International Churchill Conference

The “Man of May”

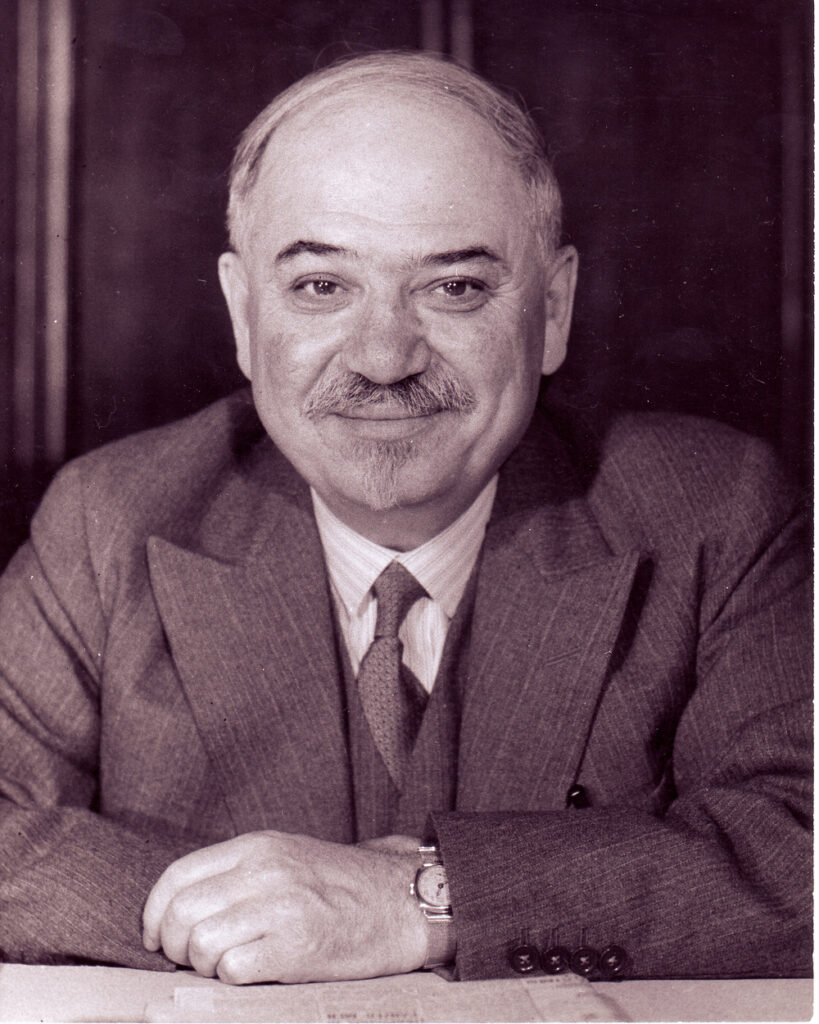

Maisky was an unimpressive little fellow—pudgy, balding, with a ragged moustache— variously derided as a “gnome,” a “sub-falstaffian figure,” and a “little Tartar Jew.” In fact, he was the son of a doctor of Polish Jewish descent and assumed the nom de plume Maisky (“Man of May”) while exiled as a young revolutionary. Many foes of the Tsarist regime had to spend time abroad, but Maisky’s biography is unusual in two ways. First, he was a Menshevik who openly opposed the Bolsheviks in 1917–18. Second, he spent five years (1912–17) in London, mostly in the Russian colony in Hampstead, where he bonded with Georgy Chicherin and Maxim Litvinvov, who became the Soviet Union’s first two foreign ministers.

Their support enabled Maisky to worm his way into the Soviet diplomatic establishment during the 1920s. His familiarity with England and his fluency in English were then vital in winning him the London Embassy in 1932, as Litvinov started moving the USSR closer to Britain and France against the mounting Nazi threat.

Maisky kept a diary during all his time in London. Although in almost daily contact with the Kremlin, he never enjoyed Stalin’s full confidence. Indeed, few ambassadors did because diplomacy was inherently problematic for Soviet emissaries—necessitating fraternization with the class enemy. Maisky’s love of Western culture and fine living inflamed Stalinist doubts, but his justification through the 1930s was that he had to woo the fringes of the British Establishment because its inner circle—the “appeasers” around Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain—was rabidly anti Soviet and ready to deal with Hitler. Maisky therefore spent much of his time cultivating press barons, key editors, and leading opposition politicians. That is how he got to know Winston Churchill.

In 1935 Churchill told Maisky that, in view of the Nazi threat, he was abandoning his long struggle against the USSR, which he did not believe would pose any threat to England for at least the next ten years. (Not a bad prediction!) “We would be complete idiots,” Maisky records him saying in 1936, “were we to deny help to the Soviet Union at present out of a hypothetical danger of socialism which might threaten our children and grandchildren.” In September 1938, when Maisky was invited for the first time to Chartwell (“a wonderful place”), he was offered pre-1914 Russian vodka at teatime. “That’s far from being all!” Churchill told him. “In my cellar I have a bottle of wine from 1793! Not bad, eh? I’m keeping it for a very special, truly exceptional occasion.” Asked “which exactly?” he replied: “We’ll drink this bottle together when Great Britain and Russia beat Hitler’s Germany.” Maisky commented in his diary: “I was almost dumbstruck. Churchill’s hatred of Berlin really has gone beyond all limits.”5

Uneasy Allies

But fortune’s wheel kept turning. By the end of 1939, the Nazi-Soviet Pact and Stalin’s Winter War against “Brave Little Finland” left Maisky out in the cold, only for him to become the toast of the town after Hitler invaded the USSR (Operation Barbarossa) in June 1941. As he noted that autumn: “Everything ‘Russian’ is in vogue today: Russian songs, Russian films, and books about the USSR.”6

Yet public enthusiasm did not seem to be mirrored at the top. Despite Churchill’s broadcast on the evening of Barbarossa and the agreement between the two governments about mutual aid, Stalin considered that the aid was one-sided: the Red Army was doing most of the fighting while the British waited to see what happened. On 30 August, with Kiev and Leningrad nearly surrounded, he sent an angry cable to Maisky: “The fact that England applauds us and curses the Germans does not change anything. Do the English understand that? I think they do. So what do they want? I think they want us to weaken. If this assumption is correct, we have to be careful with the English.”7

Maisky replied directly to Stalin, urging a personal telegram to Churchill—which he would then back up in person— explaining the deteriorating situation in detail and asking for a Second Front, or else massively increased material aid. The Soviet leader took his advice. Churchill was incredulous to receive a request to “establish this year a second front somewhere in the Balkans or France” sufficient to “divert from the Eastern Front some 30 to 40 German divisions.” He did not have that number of combat-ready troops in the whole British Army. Nor did Stalin seem to grasp the hazards of amphibious operations—unlike a man who had Gallipoli and Dunkirk engraved on his heart.8

In autumn 1941, as the Germans advanced on Moscow, friction increased between the two leaders. On 8 November, Stalin sent a lengthy list of gripes, ending with what seemed a gratuitously offensive complaint that planes “reach us broken because of imperfect packing.” When Maisky gave a translation to Churchill, the Prime Minister jumped up from his chair. “His face was as white as chalk and he was breathing heavily. He was obviously enraged.”9

The British intimated to Maisky that an “olive branch” from Moscow would be welcome after such an “insulting” telegram, but Stalin was not a man to do “apologies.” Eventually it was agreed that Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden would travel to Moscow in an effort at bridgebuilding face-to-face. And then on 30 November came another message for Churchill— truly a bolt from the blue: “Warmly congratulate you on your birthday. From the bottom of my heart wish you strength and health which are so necessary for the victory over the enemy of mankind—Hitlerism. Accept my best wishes.”10

Stalin was not in the habit of sending birthday greetings, certainly not to bourgeois imperialists. When we were working on The Kremlin Letters, I asked Vladimir Pechatnov if he could discern from the archives in Moscow who had prompted this message. No evidence was found, but I assume that credit must go to Maisky, who had got to know Churchill so well. At any rate, Stalin’s billet doux helped ease the tension. The Prime Minister sent warm thanks and followed up with “sincere good wishes” for Stalin’s birthday on 21 December. This exchange of greetings became their norm for the rest of the war. (Roosevelt did not start the practice until December 1944.)11

Approaching Understanding

In this newly cooperative atmosphere, Maisky accompanied Eden to Moscow—acting as a valued interpreter of both language and tone. Their journey was overshadowed by Churchill’s impromptu visit to see Roosevelt after Pearl Harbor, but Eden’s trip was a milestone: the first time a British foreign secretary had visited the USSR. The main business was to conclude a formal treaty of alliance, but Stalin suddenly enlarged the agenda by demanding that the Treaty include acceptance of the USSR’s borders before 22 June 1941—in other words, as stipulated in the Nazi-Soviet Pact.

This demand was problematic in Britain and totally unacceptable in the US, where it was seen as a blatant breach of Roosevelt and Churchill’s Atlantic Charter of August 1941. With discussions deadlocked, Stalin despatched Foreign Minister Molotov to London and Washington for a bout of shuttle diplomacy in May and June 1942, hoping to tie up both the treaty and a commitment on the Second Front. Maisky acted as Molotov’s interpreter during his visits to Britain.

Eventually, Stalin accepted an alternative, more general treaty, pledging twenty years of friendship, without any reference ABOVE Ivan Maisky to territory. His U-turn occurred just as Hitler began his summer offensive. It seems that Stalin backed down on the treaty in the belief, after Molotov’s trip to Washington, that Roosevelt would push Churchill into an early second front—invading France in 1942.

Backed into a corner, on 10 June the Prime Minister gave Molotov a memo in which he made positive noises about 1942 but offered “no promise in the matter.” Instead, he tried to shift the focus to 1943, on which Britain and America were “concentrating our maximum effort” and talked of a campaign, starting with “over a million men,” on which “no limit” would be set. This, Churchill hoped, would sustain Soviet morale at a critical moment, while not arousing false expectations.12

With relations already tense, July 1942 saw a major crisis over the Arctic supply convoys— offered by FDR and Churchill as a surrogate for the Second Front. On 4 July when convoy PQ 17 was in Arctic waters, Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, the First Sea Lord, overruled his intelligence staff and ordered the ships to scatter—fearful that the fabled German battleship Tirpitz had left its Norwegian port. That was a fateful decision. Up to this point the convoy had lost only three of the thirty-four merchant ships that had entered Arctic waters but, after the “scatter” order, twenty-three were picked off by enemy aircraft or U-boats. Most historians have blamed Pound for his worst-case analysis about the Tirpitz and his tendency to micro-manage.13

On 15 July Maisky and his wife Agniya were suddenly invited to dine at Number Ten with Winston and Clementine Churchill.14 On arriving, Maisky noted with foreboding that Admiral Pound was also a guest. The PM’s mood was grim. “Three-quarters of the convoy perished—400 tanks and 300 planes lie on the sea bed!” he exclaimed. “My heart bleeds.” He told Maisky that the Cabinet now had no choice but to suspend the convoys for the moment. But the Ambassador had his own contacts in Whitehall, and he asked pointed questions. Why were there only six destroyers doing close escort duty, and no battleships or aircraft carriers? What about the lack of air cover or reconnaissance? And why the “scatter” order to the lumbering merchant vessels—surely a kiss of death? Maisky had already gathered that the order emanated from Pound and he “took the greatest exception” to the First Sea Lord answering back as he “puffed away haughtily on his cigar.” Churchill supported the Admiral, though “without much enthusiasm,” the Ambassador felt.

“You are ceasing the delivery of military supplies at the most critical moment for us,” Maisky protested. “In that case, the question of a second front becomes all the more urgent. What are the prospects here?” Churchill reminded him of the memo given to Molotov on 10 June, and then elaborated on all the difficulties of crossing the Channel in 1942 and the current priority to stop Rommel reaching Cairo. “Pound, grinning in self-satisfaction, hastened to take the prime minister’s side.” Only Clementine, who was “very upset,” made “several cautious attempts” to support Maisky. “But the PM would roar and she would fall silent.”

When Churchill sent a long telegram to Stalin, seeking to explain the British predicament, Maisky urged the Boss to take “a hard stand” in reply, making clear that “if the second front is not opened in 1942, the war may be lost.” Although he found Stalin’s eventual message on 23 July “somewhat gentler” than expected, it did not pull any punches. Stalin’s tone was one of pain rather than anger. He accurately put his finger on the Admiralty’s mishandling of PQ 17, and accused Britain of lack of “goodwill” towards its ally and failure “to fulfil the contracted obligations.”15

The telegram was shrewdly aimed, questioning as it did Churchill’s sense of honour. The PM was “very hurt,” Eden told Maisky, and also “tormented that at this difficult hour there is so little he can do for his ally.” Rather than continue the telegraphic tennis match, Eden and Maisky shifted tack. “Two great men have clashed,” the Foreign Secretary remarked with a faint smile. “They’ve had a tiff….You and I need to reconcile them…. Too bad they’ve never met face to face!” Maisky reflected in his diary: “Churchill is hot-tempered,” but after an “initial emotional reaction, he begins to think and calculate like a statesman” and eventually “arrives at the necessary conclusions.”16

Mission to Moscow

Following the flare-up in late 1941, that sort of reflective process had led to Eden’s visit to Moscow in December. This time, it moved face-to-face diplomacy up to the very top with Churchill’s trip to see Stalin in Moscow in August 1942.

“It would be so good if you could be their interpreter!” Eden told Maisky. “One must be able to translate not only the words but the spirit of a conversation! You have the gift! The prime minister was telling me that when you interpreted during our talks with Molotov, he had the impression that the language barrier between him and Molotov had fallen, that it no longer existed.”17 But a repeat performance in the Kremlin did not materialise. Maisky’s star was on the wane: Stalin and Molotov suspected him of going native—or worse.

Churchill’s odyssey was truly epic: he stopped in Cairo to sort out the command crisis in North Africa and then flew on via Tehran and over the Caucasus to avoid German-controlled airspace. The meetings at the Kremlin followed a pattern familiar to earlier British visitors. A businesslike first session, during which the PM revealed plans for the “Torch” landings in French Northwest Africa and represented these as an alternative “second front.” Then came a nasty second encounter, during which Stalin accused the British of being too scared to fight the Germans. Churchill, furious, had to be dissuaded by his advisers from taking the plane home. Eventually, there was a stiff but polite finale—until Stalin invited the PM back to his apartments for a farewell drink.

There ensued a booze-up into the early hours, punctuated by a succession of choice dishes— crowned by a suckling pig, into which Stalin hacked with gusto. Conversation ranged from the elimination of rich peasants to the relative merits of Marlborough and Wellington as military commanders. (Churchill naturally favoured his ancestor, while Stalin—mischievously— opted for the Iron Duke, because he had defeated Napoleon, “the greatest menace of all time.”) The PM eventually escaped about 2:30 am. By then, to quote his memoirs, he had “a splitting headache, which for me was very unusual.” He was able to sleep off his hangover on the flight back.18

Churchill struggled to find a reason for the abrupt shift of mood between the first meeting and the second. He told the War Cabinet in London: “I think the most probable is that his Council of Commissars did not take the news I brought as well as he did. They perhaps have more power than we suppose and less knowledge.”19

Two Stalins

The idea of “Two Stalins”— friendly in person (as on the final evening) but confrontational when pressed by his colleagues— dates from this time. Indeed, it became an idée fixe for the rest of the war, helping persuade Churchill of the value of summit diplomacy and also his skill in conducting it. In March 1943, he told Eden of his continued belief “that there are two forces to be reckoned with in Russia: (a) Stalin himself, personally cordial to me, (b) Stalin in council, a grim thing behind him, which we and he have to reckon with.”20

The pattern continued. After the first Big Three conference in Tehran, the PM returned home worried that a victorious Red Army might dominate Eastern Europe, but also hopeful that his budding relationship with the Soviet leader could manage the problems. In January 1944 he told a journalist friend: “If only Stalin and I could meet once a week, there would be no trouble at all. We get on like a house on fire.”21 When the war started in 1939, he asserted that the key to the Soviet “enigma” was Russia’s national interest. As the war neared its end, he believed the key was Stalin.

This idea recurs even in his famous speech at Fulton, Missouri, in March 1946. Although now celebrated for its warning about the “iron curtain” coming down across Eastern Europe, Fulton was not a clarion call for war but for negotiation from a position of strength. He said he sought “a good understanding on all points with Russia under the general authority of the United Nations Organisation” backed by “the whole strength of the English speaking world.” Churchill’s own title for the speech was “The Sinews of Peace.”22 And that faith in personal diplomacy helps explain his zeal, during his second term in Number Ten (1951–55), for renewed efforts to “parley at the summit.”

Last Days

By this time Maisky’s day as a double interpreter was long gone. In the summer of 1943 he and his counterpart in Washington, Maxim Litvinov, were recalled to Moscow and replaced by two young proteges of Molotov—Feodor Gusev and Andrei Gromyko. Their task, Moscow made clear, was to “sign agreements” rather than engage in “exchanges of views.” In fact, Gusev seemed almost like a messenger-boy. After a welcome dinner for him, Field-Marshal Alanbrooke wrote in his diary that “Frogface” was “certainly not as impressive as that ruffian Maisky was!”23

Back in Moscow, Maisky’s wartime past finally caught up with him during Stalin’s paranoid twilight, when the London diaries were unearthed and he was imprisoned on charges of treasonous conspiracy with Britain. Only the dictator’s death saved Maisky’s life. Pardoned in 1955, he died twenty years later, a forgotten figure. But, thanks to Gabriel Gorodetsky’s prodigious and imaginative scholarship, Ivan Mikhailovich Maisky has now gained a kind of literary immortality—in the process throwing fascinating new light on Churchill and Stalin.

Endnotes

1. Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, vol. IV, The Stricken World, 1916–1922 (London: Heinemann, 1975), p. 257.

2. The term “double interpreter” was used by West German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt about his role between Washington and Moscow during the era of détente. See Kristina Spohr, The Global Chancellor: Helmut Schmidt and the Reshaping of the International Order (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 4 and 9.

3. David Reynolds and Vladmir Pechatnov, eds., The Kremlin Letters: Stalin’s Wartime Correspondence with Churchill and Roosevelt (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018).

4. Gabriel Gorodetsky, ed., The Maisky Diaries: Red Ambassador to the Court of St James’s, 1932–1943, translated by Tatiana Sorokina and Oliver Ready (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015). I also develop some points first made in my review of this book in the Times Literary Supplement, 6 Nov. 2015, p. 12.

5. Maisky Diaries, pp. 50, 68, and 124–25.

6. Ibid., p. 394.

7. Kremlin Letters, p. 38.

8. Ibid., pp. 38–43.

9. Maisky Diaries, pp. 402–04.

10. Kremlin Letters, pp. 66–70.

11. Ibid., pp. 80, 518–19.

12. Ibid., ch. 4, quoting pp. 118–19.

13. Stephen W. Roskill, The War at Sea, vol. II (London: HMSO, 1956), esp. pp. 115, 138, and 143; Correlli Barnett, Engage the Enemy More Closely: The Royal Navy in the Second World War (London: Penguin, 2000), pp. 710–22.

14. The following account of the dinner is based on Maisky Diaries, pp. 447–50.

15. Maisky Diaries, pp. 451–53; Kremlin Letters, pp. 128–30.

16. Maisky Diaries, p. 454.

17. Ibid., pp. 456–57.

18. Winston S. Churchill, The Second World War, vol. IV, The Hinge of Fate (London: Cassell, 1950), pp. 445–59; see also Birse’s notes in PREM 3/76A/12/35-7 (National Archives), and Birse, Memoirs, p. 103. For Maisky, see Gorodetsky, pp. 458–59 and 461.

19. Martin Gilbert, ed., The Churchill Documents, vol. XVII, Testing Times, 1942 (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 2014), p. 1077.

20. Martin Gilbert, ed., The Churchill Documents, vol. XVIII, One Continent Redeemed, January–August 1943 (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 2015), p. 690.

21. Martin Gilbert, ed., The Churchill Documents, vol. XIX, Fateful Questions, September 1943 to April 1944 (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 2017), p. 1534.

22. Robert Rhodes James, ed., Winston Churchill, His Complete Speeches, vol. VII (New York: Chelsea House, 1974), pp. 7285–93.

23. Kremlin Letters, pp. 281 and 390–91.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.