Finest Hour 166

My Grandfather’s Final Days

July 24, 2015

Finest Hour 166, Winter 2015

Page 06

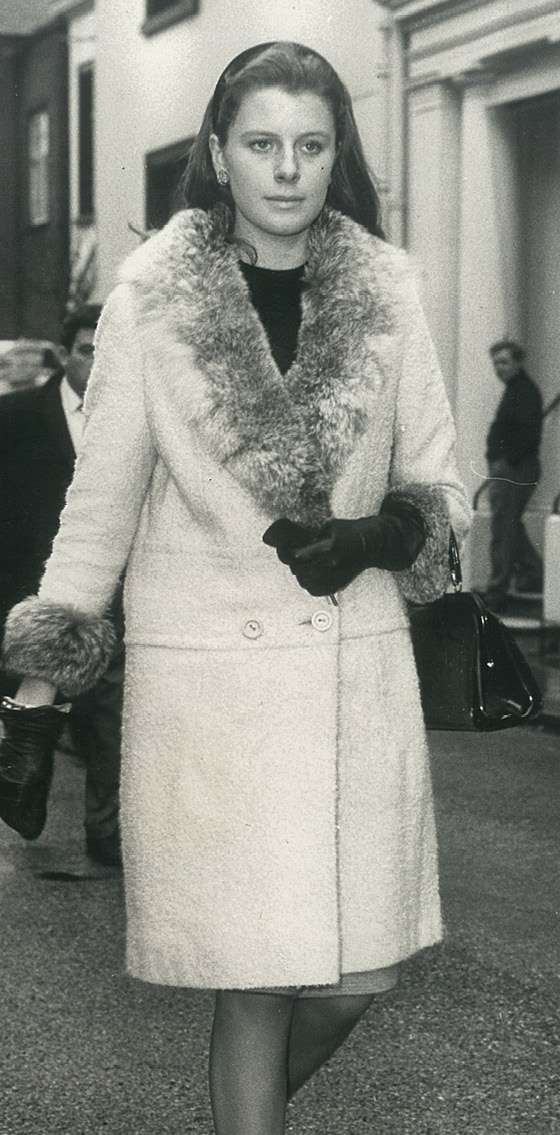

The Personal Account of The Hon. Celia Sandys

“I am ready to meet my Maker. Whether my Maker is prepared for the great ordeal of meeting me is another matter.”

—Winston Churchill speaking at the Mansion House in London on the occasion of his seventy-fifth birthday, 30 November 1949

2024 International Churchill Conference

His birthdays were always a big family occasion. The first one that I can remember clearly was his eightieth birthday in 1954 when there was a huge event in Westminster Hall. The purpose was for both Houses of Parliament to mark the day with tributes and the presentation of the portrait by Graham Sutherland, which had been commissioned as a gift for him.

His birthdays were always a big family occasion. The first one that I can remember clearly was his eightieth birthday in 1954 when there was a huge event in Westminster Hall. The purpose was for both Houses of Parliament to mark the day with tributes and the presentation of the portrait by Graham Sutherland, which had been commissioned as a gift for him.

The rumour was out that the image was less than flattering. I remember my parents discussing how he had disliked it when he had seen it two weeks earlier. He did, however, rise to the occasion and accepted it, saying, “It is a remarkable example of modern art.” As usual he had chosen the perfect words. The portrait was never seen again!

Ten years later we celebrated his ninetieth birthday at Hyde Park Gate. He had left his beloved Chartwell for the last time the month before. As we raised our glasses of Pol Roger to toast him, the unspoken thought in everyone’s mind was that the final meeting could not be long delayed.

Six weeks later, on 10 January 1965, he suffered a stroke, the effects of which worsened over the next few days.

On the evening of the 15th, I received a call from his personal secretary, Anthony Montague Browne, to tell me that my aunt Sarah was on her way from Rome. He said she would be arriving at Heathrow in the early hours of the morning and had asked if she could stay with me.

I remember driving like the wind to get to Heathrow in time and then having to run the gauntlet of a huge crowd of journalists before we could get out of the airport. The press had only heard of my grandfather’s condition a few hours before and so were hungry for information.

We went straight to Hyde Park Gate and found Grandpapa sleeping peacefully with his cat Jock curled up beside him. I don’t know if Jock ever left the bed, but every time I was there the cat lay curled up by his master.

It was clear that the inevitable was about to happen. We were all sad—for ourselves, not for him. Anyone who had spent time with him during the last few years knew that he was ready to go.

During the next nine days we had two urgent calls to go to Hyde Park Gate when it seemed the end was near, but each time he rallied. Otherwise during this period we visited once or twice a day, as much for my grandmother as for him.

Initially we had to struggle to get through the crowds of press and concerned onlookers who filled the little culde-sac day and night. After a few days, in response to a request from my grandmother, the bystanders moved to the main road and our visits became much easier.

Early on the morning of the 24th of January we received what was clearly the final call from my aunt Mary. Sarah and I raced to Hyde Park Gate. There we joined my grandmother, Mary, my uncle Randolph and my cousin Winston.

Clementine sat holding Grandpapa’s hand with his doctor, Lord Moran, sitting beside her; Randolph and Winston stood on the other side, while Sarah, Mary and I knelt at the foot of the bed. Also in the room were two nurses, whose work had finished, and Anthony Montague Browne.

No one made a sound except Grandpapa who breathed heavily and sighed. Then there was silence. It seemed as though time stood still until Clementine asked Lord Moran, “Has he gone?” He nodded.

Seventy years to the day and almost to the minute since his father, Lord Randolph, had died, Winston Churchill had slipped imperceptibly away to meet his Maker.

We all sat down to a subdued breakfast and listened to the radio as the announcement of his death was broadcast to the world.

Some years earlier the Queen had decided that her first Prime Minister was to have a Lying-in-State and a State Funeral. This was the first time such an honour had been granted to a commoner since the funeral of the Duke of Wellington more than a century before.

Preparations for the ceremony had been given the code name “Operation Hope Not” and, in true British tradition, had been worked out to the last detail some years before.

More than 300,000 people queued in the freezing cold along the Embankment, across Lambeth Bridge, back along the Thames and across Westminster Bridge to file past the catafalque in Westminster Hall, the oldest surviving part of the Palace of Westminster, where my grandfather had spent so much of his working life.

The family were allowed to slip in by a side door and watch the extraordinary sight of so many who had come from near and far to bid farewell to the man for whom they felt love, respect and gratitude.

On the day of the funeral we gathered in Westminster Hall for the journey to St Paul’s Cathedral.

The men of the family, together with Anthony Montague Browne, who had served his master faithfully and lovingly to the end, walked behind the coffin, which was borne on a gun carriage.

The women rode in the Queen’s carriages. My grandmother, Sarah and Mary were in the first carriage. My sister Edwina and I rode in the second. We had rugs and hot water bottles to keep us warm on a very cold day. We were so close to the crowds lining the streets that we could have touched them. The emotion in their faces I will never forget.

When we arrived at St Paul’s, we all lined up for the procession up the aisle. The women of the family looked as though we were in uniform. Quite independently we were all wearing more or less identical black fox fur hats.

As the bearers struggled to carry the coffin up the steps and into the cathedral, it seemed they might be going to drop it. Apparently they had rehearsed but not with a lead-lined coffin! They made it and we all followed up the long aisle where the Queen and her family were waiting.

We were told that the Queen had said we should not curtsey to her so we filed into our seats opposite the Royal Family.

After the service we processed out and watched anxiously as the bearers carried the coffin down the steps, probably an even more difficult task.

As we got back into our carriages, the Queen and her family joined on the cathedral steps with monarchs, presidents, wartime colleagues and political allies to say goodbye to the man they had come to honour.

The carriages took us to Tower Pier where, after Grandpapa had been piped aboard, there was a seventeen-gun salute. We boarded the Port of London Authority’s survey vessel, MV Havengore, for the journey to Waterloo Station. As we sailed off we could hear the band playing “Rule Britannia.”

The crane drivers on the quayside dipped the heads of their cranes in salute. This was the only unscripted part of the day and one of the most moving. The RAF flew overhead.

The churchyard of St. Martin’s, Bladon —The grave of Winston and Clementine Churchill is in the front row, third from the left. At Waterloo the coffin was placed in the guard’s van with a military escort of the 4th Hussars on constant watch.

The churchyard of St. Martin’s, Bladon —The grave of Winston and Clementine Churchill is in the front row, third from the left. At Waterloo the coffin was placed in the guard’s van with a military escort of the 4th Hussars on constant watch.

We sat down to have lunch and a glass of champagne, which we certainly needed, as the train moved off, pulled by the engine, which my then seven-year-old brother Julian had named “Winston Churchill” during the war.

Along the entire route from Waterloo to Long Hanborough, the railway was lined with people of all ages, some waving, some crying, some saluting, all of them silently saying goodbye to the man they admired. Finally we reached the small churchyard at Bladon, the burial place of Winston’s parents and his brother Jack and within sight of Blenheim Palace, where he had been born ninety years before.

The day immediately turned into a family affair, and we could say goodbye in private to the husband, father and grandfather who we all loved so much.

After the service we stood by the graveside as the bearers lowered the coffin into the grave. The silence was broken by a metallic clatter. Lying on the coffin were the shiny medals that had fallen off the coat of one of the bearers.

We were a sombre party on the train going back to London. When I got home I realized how strange the past weeks had been. It was as though I had been in a state of suspension but had now come down to earth.

Aunt Sarah and I watched the rerun of the day on television and wondered at all the events in which we had played a part.

The Hon. Celia Sandys is a granddaughter of Sir Winston Churchill. She has published numerous books on him including Churchill: Wanted Dead or Alive. She has also led many tours following in the footsteps of her grandfather. She is a trustee of The Churchill Centre.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.