Finest Hour 164

Remembrances – Without Reserve: Lady Soames and the Royal National Theatre

Winston Churchill, Parliament Square, London © Sue Lowry & Magellan PR

February 10, 2015

Finest Hour 164, Special Edition, September 2014

Page 15

By Richard Eyre

Mary Soames chaired the Royal National Theatre Board from 1988, during most of my time as director, and we became close friends. Her appointment was greeted by many people with surprise and by some with alarm. I heard it said by a Labour MP that her mandate would be to privatise the National Theatre, and by a Conservative that she was being put in to “sort out the pinkoes.”

My own response was one of curiosity: not so much as to why she had been chosen as to why she had accepted. She was not a regular theatre-goer and had no conspicuously advertised ambitions to hold public office. With hindsight I think Mary agreed because it was an adventure that she couldn’t refuse, and—perhaps an unsurprising thing to say about a Churchill—because it was her destiny. The National Theatre never had cause to regret her appointment, and neither, I think, did she.

Whatever apprehensions I may have had about Mary were dispelled during our first lunch together. “You’ll have to help me out,” she said with unaffected candour. “I know absolutely nothing about the theatre. Christopher didn’t like going.” During the meal she revealed a sharp intelligence, marked with self-deprecating diffidence (“I know nothing about anything”), a remarkable memory for names and literary quotes, and a facility for telling anecdotes larded with perfectly recalled detail and dialogue.

2025 International Churchill Conference

They often featured her father and boasted a supporting cast that included Stalin, Roosevelt, General de Gaulle, Noël Coward, Robert Mugabe and all the Mitford sisters. She once asked me to dinner with Jessica Mitford (“Richard, dear, could you bear to come to dinner to break the ice?”) Mary hadn’t seen them since Jessica had eloped to the Spanish Civil War with Mary’s then sort-of-boyfriend, Esmond Romilly.

I was particularly taken by Mary’s ability to keep several sentences bouncing in the air at once, even while she dropped her handbag on the floor, picked up the contents, draped an errant tape measure round her neck, and continued as if this were the most natural thing in the world. I remember reading a newspaper profile of Mary before I met her. “She is a great giver,” it said. “The heart comes pouring out and when it reaches you it is warm.” No one who met her could doubt that.

I did help her out as she had requested, and in return she gave herself without reserve and without condition to the life of the National Theatre. She became an assiduous student of theatre politics, of plays, of styles of production, and of the sometimes bizarre and often self-indulgent behaviour of the people who made up the world she had joined. I found her taste—in plays and in acting—to be infallible, even if she was always tentative about asserting it, and she had an unerring ear, nose and eye, for the bogus. Her loyalty never wavered, and even when concerned by hostile criticism or bad box office, or provoked by artistic controversy—the mud bath in A Mid summer Night’s Dream, the simulated gay sexual intercourse in Angels in America, the depiction of the Queen in A Question of Attribution—she remained steadfast in her support of the artistic policy.

She was not, in spite of her lineage, a natural politician or administrator; she had to work extraordinarily hard to succeed as she did at the job. She had an irreducible sense of duty, and endured without complaint a few financial crises, several bruising encounters with the architect Denys Lasdun, many Olivier award ceremonies, countless sponsorship occasions, and an infinity of meetings of the board, the finance and general purposes committee, the master plan sub-committee, the catering committee, the National Theatre development council, the National Theatre foundation, and the South Bank Theatre Board.

After Mary left the NT Board I’d meet her from time to time and we always fell on each other as old friends, hungry for gossip and comradeship. I saw her last a few weeks before she died. She was frail and her memory was intermittent, but she was still beautiful, and she still showed flashes of her old wit and great charm.

Whenever I go through Parliament Square I’ll always remember passing the statue of her father as we drove back together from the theatre—often late at night—and Mary saying: “Night, night, Papa.”

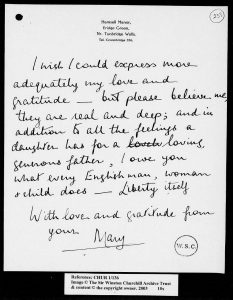

She told me once that late in his life, when he was frail and incommunicative, she had asked him if there was anything in his life that he had wanted to do but hadn’t, anything that he regretted. He replied: “I’d like my father to have lived long enough to have seen me do something good.” He would have been inordinately proud of his daughter.

Sir Richard Eyre CBE is a film, theatre, television and opera director. He was director of the Royal Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh from 1967 to 1972 and of the Royal National Theatre between 1987 and 1997. First published in The Guardian of 4 June 2014, this remembrance is reprinted by kind permission of the author.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.