Finest Hour 163

The Churchill Centre Twenty Years On

Winston Churchill, Parliament Square, London © Sue Lowry & Magellan PR

February 6, 2015

Finest Hour 163, Summer 2014

Page 48

“The Four Pillars of The Churchill Centre are Publications, Education, Research and Media.” —Laurence Geller, Chairman, 2007

Research and “Churchill Central”

To knit together the vast and diverse trove of Churchill material on the Internet, The Churchill Centre UK has combined with Bloomsbury Publishing to launch the Churchill Central website in 2015 on the 50th anniversary of Sir Winston’s death. Rather than another Churchill site, Churchill Central strives to concentrate and direct browsers to important sources of research from the various organizations. The Churchill Centre’s part in all this is largely based on Finest Hour, with some 800 articles and papers now in digital as well as .pdf form which constitute one of the broadest collections of Churchill material by leading scholars, published over the past thirty-five years. Here is a sampling of the article synopses we are preparing for Churchill Central, in Bloomsbury’s twelve chosen aspects of his life and times, with web pages you can access.

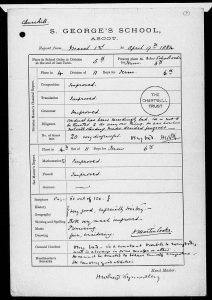

1. The Child

Eric and Hilda Bingham, “School Days: Young Winston’s Mr. Somervell,” FH 86, Spring 1995. Article: http://bit.ly/1kJvPI4 (scroll to page 20).

2025 International Churchill Conference

Robert Somervell, who instilled Churchill’s love of English, was born in Cumberland in 1851. He died in Kent, close to Chartwell, in 1933, shortly after being cited by his then-56-year-old former pupil, Winston Churchill, as the man who taught him the precious heritage of language. In My Early Life Churchill recalled this “most delightful man, to whom my debt is great…charged with the duty of teaching the stupidest boys the most disregarded thing, namely to write mere English. He knew how to do it. He took a fairly long sentence and broke it up into its components.”

In a 1935 biography of his father, Sir Donald Somervell wrote: “My father often spoke in after years of the remarkable English compositions Mr. Churchill showed to him, sometimes on subjects quite other than that which he had selected.” Winston’s imaginative essays included one in the style of John Gilpin on Rhamsinitus, hero of Philpot’s Herodotus in Attic Greek, and an elaborate essay complete with maps describing an imaginary battle in Russia. The latter closely prefigured what actually occurred on the Eastern Front between the Germans and Russians in The Great War (1914-18).

2. The Soldier

Winston S. Churchill, “The Riddle of the Frontier”; Ben MacIntyre, “Afghanistan: The Churchill Experience,” FH 147, Summer 2010. Articles: http://bit.ly/1kJwQ2Q (scroll to pages 20 and 22).

In his first book, The Story of the Malakand Field Force, Churchill poses questions as worth answering now as they were in 1898. Next, Ben MacIntyre looks at modern war in Afghanistan, and the lessons derived from reading Churchill’s book by former NATO commander Gen. Stanley McChrystal.

In 1898, Churchill wrote, “British power, having conquered the plains of India and subdued its sovereigns, paused at the foot of the Himalayas and turned its tireless energy to internal progress and development. The ‘line of the mountains’…was found to be an inadequate deterrent…. The priesthood, knowing that their authority would be weakened by civilisation, have used their religious influence on the people to foment a general rising….Only one real objection has been advanced against the plan. But it is a crushing one [and] it is this: we have neither the troops nor the money to carry it out.”

MacIntyre explains how young Churchill’s book influenced General McChrystal, who came to similar conclusions about the Afghanistan of a century later: “Churchill was a natural historian, and for all their imperial arrogance, his words carry unmistakable relevance to Afghanistan today.”

3. The Young Statesman

Sir Martin Gilbert, “What about the Dardanelles?” FH 126, Spring 2005. Article: http:// bit.ly/1kJBrC2 (scroll to page 23).

In 1915 the Western Allies attacked the Dardanelles and Gallipoli, hoping to force Turkey out of the war and aid the Russians. Failure of both operations haunted Churchill the rest of his life. Indeed some World War II historians believe his determination to avoid invading France until there was a near chance of success stemmed from his horror over losses on Gallipoli. (As Churchill confided to General Marshall in 1943: “I see the sea full of corpses.”)

Sir Martin Gilbert answers all the questions about the Dardanelles: When did Churchill first speak of this attack? Why did he think it vital? Why did he first advocate a naval operation? What was the effect of the initial bombardment of Turkish forts? Did Churchill underestimate Turkish resistance? Did he overrule his military advisers, or steamroll his demands past the War Cabinet? This is a definitive account of what actually happened.

4. Between the Wars

David Freeman, “Churchill and the Making of Iraq,” FH 132, Autumn 2006. Article: http:// bit.ly/1k-JBLAK (scroll to page 26).

For better or worse, it was the Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill who chaired the 1921 Cairo Conference which created the Middle East borders we still know today. What was Churchill’s thinking? What mistakes did he make? How, if at all, have conditions changed in the near-century since?

Churchill’s task was not easy, writes Professor Freeman. He arrived in Cairo to shouts from an Arab crowd chanting, “Down with Churchill.” In Gaza, he and his wife found a different Arab crowd, divided between “Cheers for the Minister!” and “Down with the Jews.” Ever the optimist, Churchill believed Arabs and Zionists could learn to get along. But he became increasingly exasperated with the Iraqi king he had installed in Baghdad. “We are paying eight millions a year,” he wrote Lloyd George, “for the privilege of living on an ungrateful volcano out of which we are in no circumstances to get anything worth having.” Cynics might say that little has changed.

5. The War Leader

Eliot Cohen, “Churchill and His Generals: The Tasks of Supreme Command,” Finest Hour Online. Text only: http://bit.ly/1nCPoBD.

Often misunderstood or unappreciated, Churchill’s constant auditing of his military commanders was a vital contribution to World War II victory. Churchill held their calculations and assertions up to the standard of a massive common sense, informed by wide reading and his own war experience. In questioning the feasibility of an exercise that presumed a successful German invasion of the Norfolk coast, Churchill wrote: “I should be very glad if the same officers would work out a scheme for our landing an exactly similar force on the French coast at the same extreme range of our Fighter protection and assuming that the Germans have naval superiority in the Channel.”

This is not to say that Churchill’s military judgment was invariably or even frequently superior to that of his subordinates, although on occasion it clearly was. But when his military could not come up with plausible answers to his harassing and inconvenient questions, they usually revised their views; when they could, Churchill revised his. In both cases, British strategy benefitted.

William Manchester, “The Fall of France: ‘Another Bloody Country Gone West,’” FH 109 Winter 2000-01. Article: http://bit.ly/ 1kFDeYK (scroll to page 17).

As France reeled in 1940 Churchill flew there five times to encourage his allies. “His words came in torrents, French and English phrases tumbling over each other…. No matter what happened, England would fight on and on and on, toujours, all the time, everywhere, partout, pas de grace, no mercy, puis la victoire.” They must fight in Paris, behind Paris—retreat to North Africa if need be. On his fifth visit, the French government was in Tours. “He disembarked and told a loiterer, in his appalling French, that his name was Churchill, that he was the Prime Minister of Great Britain, and that he would be grateful if they could provide him with ‘une voiture.’” When the French asked for an armistice he growled, “Another bloody country gone west.” Then he rescued Charles de Gaulle, who took with him into exile, as Churchill later wrote, “the honour of France.”

6. The Elder Statesman

Michael Wardell, “Churchill’s Dagger: A Memoir of La Capponcina,” FH 87, Summer 1995. Article: http://bit.ly/1kJjlA2 (scroll to page 14).

In 1949, visiting his friend Lord Beaverbrook on the French Riviera, Churchill listened to the triumphant tones of Land of Hope and Glory. His eyes glistened as his face became heavy with emotion. “It’s a terrible thing,” he said, “to have lived to see England brought down to ruin and the Empire lost….I’ve always said I could defend India against the world—all except the English….And what folly to slang the Americans.” After “the best feast of conversational entertainment I ever enjoyed,” he suffered his first stroke—within an hour of removing his father’s ring from his hand. Lord Beaverbrook’s companion, Michael Wardell, offers rare insights into the Churchill persona, his long friendship with Beaverbrook, and new looks into Churchill’s view of the world in mid-20th century. Just before the stroke, he paused and said: “The dagger is pointing at me. I pray it may not strike. I want so much to lead the Conservatives back to victory. I know I am worth a million votes to them.” Those might have been his last words.

7. The Man of Action

The Earl Mountbatten of Burma, “Churchill the Warrior,” FH 21-24, 1971- 72. Text only: http://bit.ly/ 1nCRSA6.

Mountbatten joined the Royal Navy in 1913 and was forever associated with the Senior Service. In World War II, before becoming Supreme Commander South East Asia (1943-46), his destroyer HMS Kelly was sunk from under him. In late 1941 he was in Hawaii (“telling the Americans what the war was like”) when Churchill appointed him Chief of Combined Operations. Mountbatten expressed a preference to go back to sea. Churchill snorted: “Have you no sense of glory? What could you hope to achieve except to be sunk in a bigger and more expensive vessel?”

In this intensely personal memoir from World War I to Churchill’s death, Mountbatten recalls the great man’s remarkable drive and pre-science, his humour and pathos, his eloquence and wit, his war leadership and his sad decline. To many who have read it, this is one of the most moving and revealing first-hand portraits of Winston Churchill. It may very well be the best of them all.

8. The Man of Words

Winston S. Churchill, “The Scaffolding of Rhetoric,” FH 94, Spring 1997. Article: http://bit.ly/ 1fUPQMj (scroll to page 14). Text: http://bit.ly/ 1nkd28F.

“The orator is the embodiment of the passions of the multitude. Before he can inspire them with any emotion he must be swayed by it himself. Before he can move their tears his own must flow. To convince them he must himself believe.” Young Winston wrote but did not publish this piece in 1897 aged only 23. Yet in sixty-years of oratory, he never deviated from its precepts. The young Churchill established four principles that a speaker must follow which he adopted as maxims: Correctness of Diction (“knowledge of a language is measured by the nice and exact appreciation of words”); Rhythm (“the sentences of the orator when he appeals to his art become long, rolling and sonorous”); Accumulation of Argument (“the climax of oratory is reached by a rapid succession of waves of sound and vivid pictures”); and Analogy (“an apt analogy favours the belief that the unknown is only an extension of the known”). His formula for a good speech remains as sound now as ever. This essay was never formally published before its appearance here.

9. The Man of Leisure

Barbara F. Langworth, “Churchill and Polo: The Hot Pursuit of his Other Hobby,” FH 72, Third Quarter 1991 Article: http://bit.ly/ 1nkdGmx (scroll to page 24).

“He rides in the game like heavy cavalry getting into position for the assault. He trots about, keenly watchful, biding his time, a master of tactics and strategy. Abruptly he sees his chance, and he gathers his pony and charges in, neither deft nor graceful, but full of tearing physical energy—and skillful with it too. He bears down opposition by the weight of his dash….” This is not a description of Churchill the war leader, but Churchill the polo player. WSC played his first chukka as a cavalry subaltern in 1895, and his last as a 52-year-old Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1926. He always played with his right arm strapped to his side to prevent it from ‘going out’ as a result of a dislocation in his youth. Even with his arm immobilized he was a serious threat on the field, and in 1897 he was key to his regiment, the 4th Hussars, winning the Inter-Regimental Championship.

Hugh Newman, “Butterflies to Chartwell,” FH 89, Winter 1995-96 Article: http://bit.ly/ wrzqix (scroll to page 34) Text: http://bit.ly/ 1v8SiTE.

“This is Winston Churchill speaking. I should like some butter- flies to liberate in my garden. May I come and see your butterfly farm and discuss a plan?” L.W. Newman, the “farmer,” was astonished. It was 1939. War was coming. Yet Churchill was thinking Lepidoptera.

Churchill had been entranced by butterflies since boyhood, especially the exotic tropical species he found in India and South Africa. Newman and his son Hugh supplied chrysalises which he watched develop, careful not to disturb a single insect. War intervened, but in 1946 Churchill rang again, showing Hugh a small summer-house: “Take the roof off it, if you like, and put a glass one in its place…. Let me have your plan soon. And let it be a plan of action.” Ever since, Chartwell has been home to butterflies—peacocks, tortoise shells, red admirals, painted ladies, swallow-tails—and the plants that attract them. “I am certain,” Newman writes, that “there was a great resurgence of the butterfly population in that part of Kent—thanks to Mr. Churchill.”

10. The Painter

David Coombs, “Charles Morin and the Search for Churchill’s Nom de Palette,” FH 148, Autumn 2010. Article: http://bit.ly/ 1nkeaJC (scroll to page 31).

Churchill’s first commercial exhibition of his paintings, in 1921, was at the Galerie Druet, a Paris establishment specializing in post-Impressionists. It resulted in six sales—but under the name “Charles Morin,” Churchill’s pesudonym. It was an odd choice, because an artist by that name had actually lived. Charles Camille Morin (1846-1919) was a well-known French landscape painter with whose work Churchill may have been familiar. Why Churchill chose the name of an artist so recently deceased is a mystery, but there is no doubt that it was intentional. In 1941, Edward Bruce of the Smithsonian Institution asked President Roosevelt to forward an luncheon invitation to “Charles Marin”—a jocular allusion to Churchill. A series of telegrams ensued between Washington and London enquiring about “the Prime Minister’s nom de palette.” Churchill’s private secretary finally replied: “Correct name is CHARLES MORIN not repeat not MARIN.’ This article, by the leading historian of Churchill’s work, illustrates eight paintings in colour.

11. The Family Man

Diana Cooper, “Winston and Clementine,” FH 83, Second Quarter 1994. Article: http://bit.ly/- 1nCTERP (scroll to page 10).

Famed for her beauty and the “durable fire” of her marriage to Alfred Duff Cooper, Lady Diana Cooper was early admitted to a delightful friendship with Winston and Clementine Churchill, which she reflects upon here with her penetrating mind and capable pen. This obscure tribute to the Churchill marriage, published shortly after Sir Winston’s death, was unknown to her son, Viscount Norwich, who kindly gave us permission to republish.

“Winston Churchill, not in his earliest youth, chose most wisely and most well,” she wrote. “His bride could have figured in a Homeric story, [suggesting] a goddess of the infant world. Blood coursed through the marble, flushing it with animation, warmth, sometimes rising to passionate heat in partisanship of a cause. She often knew the sheep from the goats better than Winston did….

“I often put myself in Clemmie’s shoes, and as often felt how they pinched and rubbed till I kicked them off, heroic soles and all, and begged my husband to rest and be careful. Fortunately, Clemmie was a mortal of another clay…”

12. The Legacy

Alistair Cooke, “Churchill at the Time: A Retrospective,” Churchill Proceedings 1988-1989. Text only: http://bit.ly/ oSjZ6t.

Speaking at the 1988 Churchill Conference at Bretton Woods, site of the famous 1944 Monetary Conference, the well-known BBC correspondent traced his memories of Churchill from his own youth in Manchester to the 1930s, explaining why it was so difficult for Churchill to get his message across about the threat of Nazi Germany: “It is very hard now, thanks to television and the abolition of front line censorship, to imagine what those terrible events conveyed. Today we see a war on the nightly news and say, ‘What are we doing there?’ when we get a casualty list of 1000 in a week. It is today impossible to get used to the idea that we could lose 200,000 men in one week. Those years, especially, have been over-dramatized, because our knowledge of the tremendous drama to come makes us see Churchill in the 1930s as a rejected giant, a lonely, stubborn hero. Most of us here would like to think that, had we been in Britain in 1934-36 we should certainly have been on his side. In fact I don’t think ten percent of us would have been with him….We must remember that even by the 1930s the country was exhausted. There were two slogans going around: “Peace at any Price” and “Against War and Fascism”—surely two of the silliest slogans. One might as well be “Against Hospitals and Diseases.”

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.