Finest Hour 178

Chartwell and the National Trust

Churchill’s painting studio

March 25, 2018

Finest Hour 178, Fall 2018

Page 30

By Katherine Carter

Katherine Carter is Project Curator and Collections Manager at Chartwell.

Last year, Chartwell marked fifty years since its first opening to the public. Today, with more than 200,000 people visiting the house and gardens each year, Chartwell remains one of the National Trust’s most popular properties, and Director General Dame Helen Ghosh recently described it as “a jewel in the crown of the National Trust.”1 But what has it been like to care for a national landmark for half a century, and what awaits Churchill’s beloved home in the coming years?

When Winston Churchill passed away in January 1965, Chartwell entered a very different phase in its long history: one of purposeful curation, public accessibility, and memorialisation. Lady Churchill decided to move to London following her husband’s death and left the house in June of the same year.

Although the National Trust had owned the house for nineteen years prior, and were able to make some preparations in advance, it was not until 1965 that they had a hand in its presentation, working closely with Lady Churchill, her daughter Mary Soames, and Lady Churchill’s former secretary Grace Hamblin, who became the first Administrator. As Martin Drury observed, “it was rare for a house to come to the National Trust ‘in full sail’ in this way.”2

2025 International Churchill Conference

Legacy Connections

The he involvement of, and consultation with, the family continued beyond the initial opening. As rooms were altered, discussions on presentation were made. Mary Soames sometimes advised on the choice of furniture, for example with the choice of furnishings in Lady Churchill’s sitting room, which opened much later in 1981. She would also advise on the garden, being involved in discussions of planting around the Marycot, and as recently as 2011 she planted new Churchill Roses in her mother’s rose garden.

When the house first opened in June 1966, Lady Churchill returned to Chartwell, greeting the long queue that formed to the north of the house along the forecourt. From that date on, she received regular “bulletins” from Grace. Each Sunday evening there would be a phone call to Chartwell to ask how many people had visited that week. The numbers must surely have delighted them. Between the June opening and the house’s closure for the season in October, there had been more than 150,000 visitors, even though the house was only open a few days each week.

Upon opening, the spirit of Chartwell was maintained by Grace, who had worked for the Churchills since the early 1930s. The Head Gardener, Mr. Vincent, had similarly been there when the Churchills were in residence. He continued to grow the potted plants that Lady Churchill liked to have in the house, regal pelagoniums in particular, and to arrange the flowers. These living connections to the time the house was displayed to represent made Chartwell truly “authentic” in a way that other National Trust houses often struggle to emulate, having come into the Trust after either a period of decline or a succession of sales.

Inside

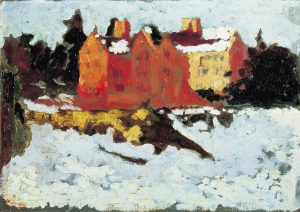

The National Trust remain faithful to the vision of displaying Chartwell as a family home, though there have been a number of changes since the first opening in 1966. The Studio, for example, first opened in 1968 but looked markedly different compared to how the space can be seen today. The sparseness of the paintings displayed upon opening bore little resemblance to how Churchill would have known his Studio, which saw canvases cover the walls from floor to ceiling. As more of his paintings came to Chartwell, however, from the private collections of Lady Churchill as well as her daughters Lady Audley and Lady Soames, the Trust were able to create a much fuller and more authentic display. The Studio came to provide more interpretation of Churchill’s paintings as well as explanation as to how the process of painting was such a key element in his life. The paintings cover a range of subjects and techniques and are from the span of Churchill’s time as a painter in oils from the 1910s to the 1950s. This variety and the presentation of the paintings in the location of their creation or completion (a place created by Churchill specifically for this purpose) enables visitors to appreciate fully Churchill the artist.

Further changes to the Studio took place in the 1970s. The basement of the main house had been full of surplus furniture and gifts given to Churchill by governments, institutions, and individuals, some of them still in the boxes and packing cases in which they arrived. In 1974, Jean Broome, Grace’s successor as Administrator, wanted the basement cleared, and so the decision was made to put as many of the items on display as possible. These items largely went to an annex in the Studio, though they bore no connection to the story of Churchill and his passion for painting and felt somewhat incongruous in that space. The changes over the course of the National Trust’s tenure were not limited to the Studio. Initial interventions had included the knocking-through of walls and transformation of stairs, all under the watchful eye of Lady Churchill. Later changes included the opening of a Sitting Room in 1981, this time with the guiding hand of Lady Soames. This room had previously served as a “visitor holding area” and also a VIP room. In addition, the shop that had been in the main house in the pre-war kitchen on the lower ground floor was relocated to its own building adjacent to the car park, and the display of the kitchen was resurrected in 1992.

Outside

In the gardens, there were also considerable changes. The statue by Oscar Nemon of Winston and Clementine, which today looks out across the lakes, was only added to the gardens in the early 1990s. There are some reservations about its likeness to Clementine, with her features appearing harsher, but this did not prove an obstacle to the grand event of its unveiling by the Queen Mother, with a wonderful talk by Lady Soames.

The garden features themselves have also seen great change. The kitchen garden, for example, was grassed over in 1965 in an effort that the maintenance should be “simple and labour saving.”3 This meant, however, that the use of the land within Churchill’s brick walls was entirely artificial and wholly unlike how the family used that part of the garden. In 2006 the decision was made to recreate the Churchills’ kitchen garden, which was such an important part of Chartwell life, supplying not only Lady Churchill’s flower displays but even providing provisions for their London residences, with 10 Downing Street receiving deliveries of fresh fruit and vegetables throughout the war. Today the fruit and vegetable stand in the garden allows visitors to take a piece of Chartwell home with them. Alternatively guests, like the Churchills’, might find themselves feasting on the kitchen garden’s produce in our Landemare Café, named after the Churchills’ wonderful cook.

Sadly, there have also been changes entirely beyond the National Trust’s control in the wider estate, resulting from the Great Storm of 1987. Extensive damage to the gardens and woodland saw the loss of around eighty percent of the trees. The nineteenth-century trees planted by the Campbell Colquhouns, the family who lived at Chartwell before the Churchills, were almost entirely lost. A few weeks ago, the team at Chartwell marked thirty years since the Great Storm, and it is remarkable to look out across the estate today, recalling how much woodland was lost, and marvelling at how well the woodlands have grown and developed since.

New Directions

Alongside these obvious and visible changes and transformations are more subtle changes which aid the National Trust in its care for Chartwell. The development of the science of conservation, in particular, has transformed the care of collections from a simple process of cleaning to a scientific and highly technical process of preventive conservation. Through the careful management of the environment, from the humidity to dust levels and light monitoring, we are able to give the best possible care to ensure that Chartwell’s collections are preserved and safeguarded for future generations to see and enjoy.

So, after half a century of providing access to Churchill’s home and caring for the house, garden, and collections, what are the next fifty years likely to bring? We are at a crucial point in the story of Winston Churchill’s legacy, and, since Chartwell is a key location to share his stories and achievements, it is our obligation to ensure that Churchill remains relevant. As time passes, we are losing the generation who remember his achievements in the Second World War, and his heroism is passed down rather than recalled. A presumption that visitors know and understand the stories of his life before they walk through the doors is no longer accurate. We must engage new, diverse and younger audiences, and measures must be taken to interpret Churchill’s home in such a way that visitors with less pre-existing knowledge of the man can enjoy it and be inspired to learn more about him.

In September 2016, the National Trust launched an appeal to reinvigorate Churchill’s legacy at his home. One of the ways this will be done is by safeguarding the collection and giving it resonance in the twenty-first century. A large part of the collection on display at Chartwell has been on long-term loan to the property. These items are increasingly important with the passage of time, offering a direct connection to Churchill through his cherished possessions, each one of which has a fascinating story to tell. The Trust’s fundraising efforts so far have been very successful, with the majority of items within this collection recently purchased and therefore guaranteed to remain on display at Churchill’s future home for future generations to enjoy. The fundraising campaign, however, continues, because there is one further item which has not yet been secured for permanent public display: the Nobel Prize for Literature awarded to Churchill in 1953 and comprising a large medal and presentation document. [See the preceding story.]

The Nobel Prize is a fascinating object. It was awarded in 1953 for “his mastery of historical and biographical description as well as for brilliant oratory in defending exalted human values.”4 It was received by Lady Churchill, who admitted ahead of the presentation ceremony that she was having an attack of “stomach butterflies,” commenting to her daughter Mary that “I have never had to read a message from him on such an important occasion before.”5

Having been on display at Chartwell for more than half a century, it has become an integral part of Chartwell’s narrative. It is also inherently connected to the place. The Study, from which so much of Churchill’s writing was undertaken, is just two rooms away from where the Nobel Prize is displayed. The accompanying certificate [see p. 28] includes an image of Chartwell. It is moving to think how commonly known it was that Chartwell was a vital part of Churchill’s work.

Churchill’s Chartwell

Beyond the collection, the National Trust is undertaking a wider “Churchill’s Chartwell” project, which is set to bring in new audiences as well as enhance connections with existing ones. From opening new spaces, developing improved interpretation, and expanding our learning, outreach, and volunteering programmes, Chartwell is committed to play its part in keeping Churchill relevant in the twenty-first century. The National Trust’s vision remains to maintain the presentation of Chartwell as a much-loved family home, but it will do so in a way that will inspire a new generation to engage with Churchill’s history, his love of Chartwell, and how he continues to affect our lives today.

The “new rooms” will include Sir Winston’s bedroom and bathroom, the secretaries’ room, and Sarah’s bedroom, which will provide a new space to tell the stories of all the Churchill children. None of these spaces has ever been open to the public before. They will now be available to see by tour of the house as and when they are ready for opening, which will be phased across the three years of the project.

Whilst Sir Winston’s bedroom requires less intervention, as we are very lucky that it remained largely as Sir Winston left it in 1964, the other rooms require considerable research and transformation of the spaces. The secretaries’ room, for example, will provide a new and exciting way to tell the story of the army of secretaries who supported Churchill in both his literary and political tasks. Working until the early hours of the morning, the dedication and resilience of these individuals was a vital part of Winston’s work, and they were integral to life at Chartwell. The room itself has remained semi-historic, but bears little resemblance to its original appearance. For this and many other elements of the project, Chartwell has undertaken an “oral history” project to capture the insights and recollections of those who were so lucky to have known the Churchills and seen Chartwell when it was their home.

This is such an exciting time for Chartwell, and as I enter my fifth year at this incredibly special place, it is a genuine honour and privilege to play a part in securing Churchill’s legacy for future generations. Sir David Cannadine said of Churchill’s beloved home, “It is through Chartwell and its profoundly personal collection that we can most vividly and most memorably come to know this extraordinary man.”6 Chartwell is unique and synonymous with Winston Churchill in a way unlike any other place he stayed or visited. By telling his stories and those of his family in new and dynamic ways, his home of more than forty years will ensure that the record of his life and achievements remains relevant, captivating, and truly unforgettable.

Endnotes

1. Extract from a speech given at Chartwell fiftieth anniversary event, 30 June 2016.

2. Martin Drury, interviewed in 2015 by Jeremy Musson. He is a former National Trust Director General who knew Chartwell as a young man and was the National Trust’s Curator

from 1973 to 1981.

3. Lanning Roper, quotation taken from records at Scotney Castle, National Trust. Roper was Chartwell’s Garden Adviser, worked closely with Lady Soames upon Chartwell’s opening, and continued to work with the gardens until 1980.

4. The Nobel Foundation, 1953.

5. Lady Churchill, quoted in Life magazine, 14 June 1963, p. 96.

6. Sir David Cannadine speaking at the launch of the National Trust’s “Keep Churchill at Chartwell” appeal in September 2016.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.