Finest Hour 199

Elizabeth the Great

Robert Courts (seated in lower right-hand corner) watches the new King’s broadcast on television monitors in the House of Commons

April 20, 2024

Inside the House of Commons

Finest Hour 199, Special Issue 2022

Page 24

By Robert Courts

Robert Courts is Member of Parliament for Witney. His constituency includes Bladon, the burial site of Sir Winston Churchill.

The Member of Parliament for Witney describes the scene inside the House of Commons when news started to break of the death of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

When the tectonic plates of history move, the great living organism that is the House of Commons feels the shift.

On Thursday, 8 September 2022 the House has assembled to hear new Prime Minister Liz Truss open a General Debate on energy costs, one of the most pressing issues of the summer. MPs from both sides of the House are keen to hear the PM explain her new policy and then to raise their constituents’ queries.

Yet the Prime Minister has not spoken for long when she sits down. Clearly events are rapidly overtaking. A note is passed directly to freshly appointed Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster (a key, coordinating role at the top of Government) Nadhim Zahawi suggesting that something major is happening. He leaves the Chamber, returns, and confers with the Speaker before rushing, swiftly and with head bowed, to confer directly with the Prime Minister. The serious expressions etched on both their faces make only too clear that this is not a mere policy correction from officials. On the other side of the despatch boxes, the Leader and Deputy Leader of Her Majesty’s Loyal Opposition both leave with similar speed. This is unusual. If the PM is present, so is the Leader of the Opposition. If the Leader leaves, the Deputy stays. For both to leave is a sign most serious. “The Queen?” Murmured rumours ripple around the rapidly emptying benches.

2024 International Churchill Conference

By now it is clear that the Speaker is about to say something. A short statement clutched in his hands, his usually jovial face etched with tension, he stands to call for order midway through the speech by Scottish National Party leader Ian Blackford. This too is unusual. Normally Mr. Speaker waits until the end of an MP’s remarks. But the news is out, tearing round the world, and his statement cannot wait:

I wish to say something about the announcement that has just been made about Her Majesty. I know that I speak on behalf of the entire House when I say that we send our best wishes to Her Majesty the Queen, and that she and the royal family are in our thoughts and prayers at this moment.

The Palace never makes a statement about Her Majesty’s health. Never. This must be serious. The debate continues. But the House’s thoughts are elsewhere. Silently, members slip away, to speak to each other, to watch the news, to scroll through social media. What can this be? Surely it is not serious. We have been here before. She is elderly but in good health. Why she only saw the new Prime Minister two days ago. She approved new ministerial appointments just yesterday.

Ministers dash back to their departments, checking and cross-checking that the plans for Operation London Bridge—drawn up over many years and regularly updated—are in first class shape. Nothing must be forgotten. Of course, it probably will come to nothing (it never does, does it?), and Her Majesty shall live forever. But it would be a terrible thing to be wrong. The Queen’s family are dashing to Balmoral. This must be something, “a significant event,” says one news source. But hopefully not that. Surely not that.

Six thirty in the evening now, a damp evening, the blue skies not dispelling the grey that somehow still overhangs. There are spots of rain in the air. The world stops. People on the street, stop. Everywhere people stop and stare at their phones lighting up. Strangers look at each other, not talking—there is nothing to say. It has happened. The thing that we never wanted to happen but always knew must happen, has happened. She is gone.

First Reactions

All down the Nation’s High Street of Whitehall, through a red sunset, flags are lowered to half-mast: at the Foreign Office, the Treasury, Downing Street, and the Ministry of Defence. The mourning has begun. The enormous banner above Parliament’s Victoria Tower lowers slowly in the soft breeze. Westminster Hall, that ancient venue of historical activity, stands still, silent, and, for the moment, empty. Soon it will once again be the focus of the world’s attention.

The Prime Minister— what a challenging and truly extraordinary first week for her— confirms the sad news in a short speech outside 10 Downing Street. A new Prime Minister and now a new Monarch in one week— unprecedented in all British history.

At Buckingham Palace, thousands are gathering. The huge road leading to the Palace—the Mall—is closed, as multitudes start to stream towards the Palace gates, some clutching flowers, all just wanting to be there, to pay their respects because it is “the right thing to do.” Already the world’s media have set up a tented village on one side. This event is seismic: for our country, for us individually, and for the world. It will be the biggest funeral in history.

Friday, 9 September

The next day passes in a blur of activity. There is work to be done. The rolling news reminds us constantly that this is real. All constituency meetings and public ministerial meetings or appearances are cancelled. Every detail of what is to come must be pored over, distilled, challenged, reexamined, confirmed, and carried out. Whether your part is large or small, public or private, everything must be right. For Her, no detail is too small. In the flurry of telephone calls, papers, and meetings, all is as it should be. The plans are in place, the system is working. The glorious majesty of Palace and State combine in sad, yet serene and purposeful activity.

The House meets. Led by the Chaplain to the Speaker of the House of Commons, all observe a minute’s silence in memory of our late sovereign Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. Then begin the tributes, led by the Prime Minister, lasting all day and continuing far into the evening, interrupted only by a special broadcast: His Majesty The King will address the nation at six o’clock. It does not sound right, “the King.” The old title in its new context underscores the magnitude of events.

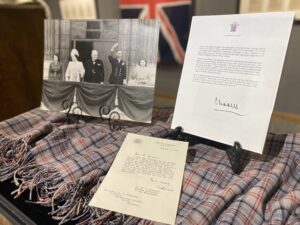

His Majesty’s sad, dignified face appears on the television screens mounted only two years ago in the House Chamber—a legacy of Covid sitting arrangements. The King’s speech is electrifying. He says everything he needs to say and everything we need him to say. Suddenly, powerfully, undoubtedly, he is King, our King—no longer Charles, Prince of Wales but King Charles III. He stuns the House into silence. Normally loud and loquacious MPs are lost for words in the face of their new sovereign’s searing grief and towering dignity. “Wow. Wow,” says one. “He is going to be a great King,” another manages to say. For once, the House agrees. Entirely.

Tributes from the House run for two days, well into Friday and Saturday night. The Speaker, exceptionally, allows Ministers to speak from the backbenches, and many take the opportunity. Normally, when MPs accept ministerial office, they are only allowed to speak from the despatch box on their own ministerial business or, if they are a whip, not at all. But on this occasion all MPs are permitted to speak: for themselves, for their families, and for their constituencies. Such is the weight of numbers that Members are allotted only three minutes each. Three minutes, to say all that you and your constituents want you to say, to explain what seventy years’ faithful, faultless service means to everybody. A tall order indeed.

Saturday, 10 September

I am called in the early evening, towards the end of the day’s speeches and some six hours into the debate. I describe my constituency’s first contact with the young girl who was to become our greatest queen. It came when West Oxfordshire’s most famous son, Winston Churchill, stayed with the Royal Family at Balmoral during the reign of George V. To his wife Clementine, he wrote: “There is no one here except the Family, the Household and Queen Elizabeth—aged 2. The last is a character. She has an air of authority and reflectiveness astonishing in an infant.…”

“How extraordinary,” I say to the House. How incredible—and yet not surprising at all—that the Queen, whose easy authority would make her the most famous and revered woman in the world, was displaying it at such a young age. How fitting that it was noticed and remarked upon by the man whose destiny it was to be our greatest—and Elizabeth II’s first— Prime Minister.

This peerless monarch remained both Olympian and possessed of the common touch, almost as if she were the nation’s grandmother as well as the Armed Forces’ supreme commander. The Queen was a constant but a unifying constant: the one person whose portrait you could see and which would always bring comfort and inspiration. She somehow remained timeless while always adapting to the times, even as they swirled and changed around her. The blood of the Kings of Wessex may have flowed in her veins, but only she could have pretended to parachute into an Olympic stadium with James Bond.

The House of Commons spoke as one. Her Majesty’s United Kingdom spoke as one. The Queen was us, and we were her. But at this moment of sadness, as we mourn what is lost, we gladly greet what is to come. In our new King, we see our late Queen’s sense of duty and constancy living strong. Whilst we grieve, we say with strengthened voice that ageless rallying cry, “God Save the King!” And God Bless the Queen. The Queen— Elizabeth the Great.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.