Finest Hour 199

“A Happy Scene”

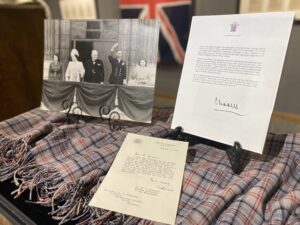

Churchill at Balmoral with Prince Charles, 1952

April 20, 2024

Churchill and Balmoral Castle

Finest Hour 199, Special Issue 2022

Page 19

By Alastair Stewart

Alastair Stewart is a public affairs consultant, freelance writer, and Chair of ICS Scotland.

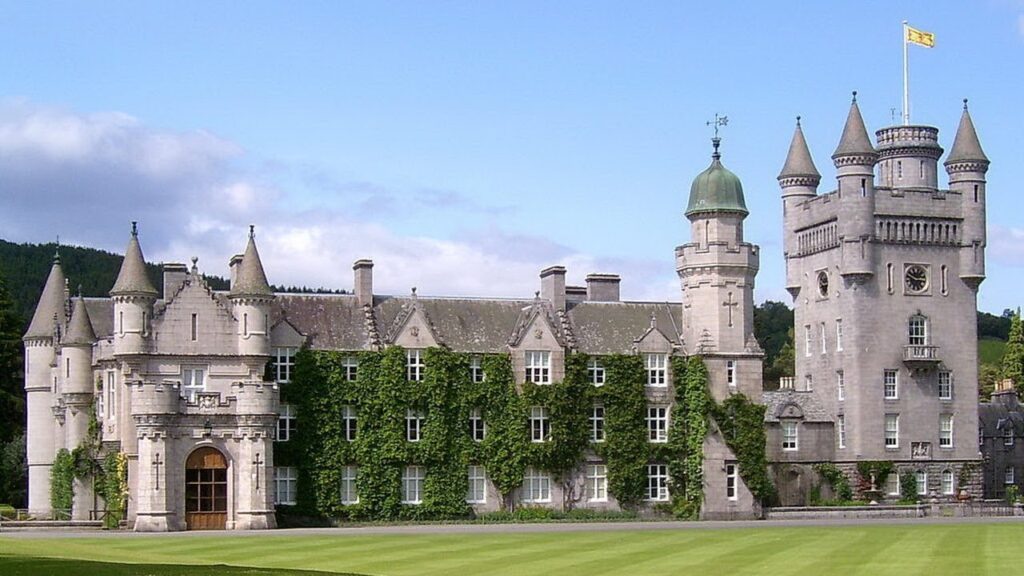

When Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II died at Balmoral Castle in Aberdeenshire on 8 September 2022, much was made about the location. Not since Scotland was an independent kingdom has any monarch in Great Britain died north of the border. Another footnote to history is that Balmoral was where Winston Churchill first became acquainted with the young princess who would become the United Kingdom’s longest reigning monarch. Even then, Churchill was no stranger to the castle.

British prime ministers have had a varied history with Balmoral. In the final days of her life, Queen Elizabeth II welcomed Liz Truss to the castle and invited her to form a government. Usually the handover takes place at Buckingham Palace. Some media incorrectly reported that Balmoral had never before witnessed such a ceremony. In fact, during the reign of Queen Victoria, the 3rd Marquess of Salisbury accepted a commission at Balmoral to form a government in 1885, although the new prime minister subsequently “kissed hands” with the Queen at Windsor.¹

Balmoral has been the Scottish home of the Royal Family since it was purchased for Queen Victoria by Prince Albert in 1852, having been first leased in 1848. The entire estate boasts approximately 50,000 acres of land. Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli complained that “carrying on the government of the country 600 miles from the metropolis doubles the labour.”² On one visit, the Spartan hospitality played havoc with “Dizzy’s” gout and incited an attack of bronchitis.³ Lord Salisbury referred to Balmoral as “Siberia.”⁴

2024 International Churchill Conference

Edward VII

Churchill’s long association with Balmoral echoed his relationships with successive monarchs, but his very first encounter with the name had nothing to do with Scotland. In an ironic twist, after escaping from a Boer prison in South Africa, Churchill took refuge at the Transvaal and Delagoa Bay Collieries at Witbank, near the Balmoral railway station. He also passed the mining town of Dundee. The namesake association with Balmoral improved after 1899, although Dundee was to prove a contentious constituency for the future Member of Parliament from 1908 to 1922.⁵

In 1902, Churchill, just twentyseven and a member of the House of Commons for less than two years, was commanded to Balmoral by King Edward VII. Like the Royal Family, Churchill typically spent the late summer and early autumn in Scotland engaged in social and sporting occasions. The isolation of the Scottish Highlands may have been a favourite of kings and queen, but “Monarchs in those days subjected themselves to more social intercourse with politics.”⁶

In a letter of 27 September 1902 written to his mother, Lady Randolph Churchill, young Winston reported that “the King has gone out of his way to be nice to me.” As a young man in a hurry, Churchill encouraged his mother to “gush [to the King] about my having written to you saying how much etc. I had enjoyed myself there.”⁷

By the following year, Churchill’s fortunes were a bit different. There was increasing disagreement within the Conservative party about protectionist tariffs favouring trade with the British Empire. Churchill was already operating with the Liberals as an ardent free trader before formally crossing the floor from the Conservatives to the Liberals in 1904. “I’m going to Dalmeny [Scotland] tomorrow,” he wrote to his mother. “I have put my name down at Balmoral—but I fear I am still in disgrace.”⁸

George V

Towards the end of September 1911, Churchill, then serving as Home Secretary, was invited to stay once more with a new monarch at Balmoral. Churchill did not at first enjoy the same easy relationship with King George V that he had with Edward VII.⁹ Churchill found George stiff and humour-less. In a letter to Clementine, he described the attendees at Balmoral as “unexciting” and felt “it would be jolly” if she were there. It was not customary for ministers’ wives to be invited, however, and Clementine remained at her own family’s seat in nearby Airlie Castle. Churchill added that “the King talks too much about affairs,” and Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George “made less of a good impression than last year.”10

The 1911 visit’s high point was the arrival of Churchill’s new red automobile, costing £610. Churchill had intended to drive his fifteen horse-power, four-cylinder Napier Landaulette to Balmoral, but there was a hitch. He had ordered the car to be painted a “Marlborough hue” but did not specify the shade. Consequently, the car was not ready in time. Instead he drove it to Airlie Castle and through Scotland after his stay at Balmoral while “relishing the Napier’s power and handling.”11

The next day Churchill went to meet Prime Minister H. H. Asquith at Archerfield, the enormous house lent by Asquith’s brother-in-law on the coast of East Lothian. It was here that Asquith invited Churchill to take over as First Lord of the Admiralty.12

The following year in mid-August, the First Lord and his family went on a cruise in the official 4,000-tonne Admiralty yacht HMS Enchantress. The tour followed the Scottish coast until, in mid-September, Churchill broke their holiday to visit his Dundee constituency. This also enabled Churchill to inspect naval establishments on the River Tyne and Aberdeen Bay, from where Winston and Clementine were bidden to dine at Balmoral.13

In September 1913, there was a repeat cruise up the Scottish coast. Churchill once again stayed at Balmoral, this time overlapping with a visit by Andrew Bonar Law, then in his second year as Conservative leader. Circumstances were fraught. A day before arriving, Churchill received a warning from Asquith that the “Royal mind obsessed” about the Irish question. In March 1912, Bonar Law had sought to involve the Crown in the Irish issue by urging the King to dissolve parliament, an act Asquith called unconstitutional.14 Aided by the friendliness of the highland air and royal hospitality, however, Churchill used his time at Balmoral to speak with Bonar Law constructively about Ireland. The outcome was a series of secret meetings with Asquith about a special status for Ulster and Home Rule.15

On a much different topic, Churchill wrote to Clementine: “Last night I had a long talk with the young Prince [of Wales, aged nineteen]. They are worried a little about him, as he has become so v[er]y spartan—rising at 6 & eating hardly anything. He requires to fall in love with a pretty cat, who will prevent him from getting too strenuous.” History can be the judge of that advice about the future King Edward VIII.16

Sixteen years later and back in the Conservative party, Churchill visited Balmoral on 25 September 1928 in his capacity as Chancellor of the Exchequer. He wrote Clementine to say, “I am tired by a racketting journey,” but found himself in some isolation with the Royal Family. Poignantly he said, “There is no one here at all except the Family, the Household & Queen [sic, Princess] Elizabeth— aged 2. The last is a character. She has an air of authority & reflectiveness astonishing in an infant….”17

On the 27th, Churchill wrote that he enjoyed a “hardworking day’s stalking 10 till 5.30 always on the move,” and “I killed a good stag 10 pointer.” He added, “The King is really v[er]y kind to me & gives me every day the best of his sport.” But sport and politics were never far removed, and “yesterday we had a most interesting talk after picnic lunch about Guarantees, Baldwin’s Dissolution in 1923, [and Lord] Curzon’s chagrin at not being P.M.” Amusingly, Churchill notes, “H.M. also shares my views about the Yankees & expressed the same unpicturesque language.”18

George VI

Balmoral played a less significant role during the Second World War when Churchill first became prime minister. The Royal Family did not visit the castle during the first two years of the conflict. They returned for the first time in August 1941 and again in September 1942. In August 1943, the Royal Family stayed for five weeks, the most extended break the King had throughout the war. His breaks were few in those years and never without interruption.19

Churchill adhered to wartime rationing but benefited from wellwishers worldwide, including food parcels from President Franklin D. Roosevelt and game from Sandringham and Balmoral sent as personal gifts from the King. Labels were used to ensure the game, freshly shot, arrived in the kitchens of Downing Street.20

In July 1944, Churchill telegraphed Roosevelt twice to urge another Big Three meeting following the 1943 conference with Josef Stalin in Tehran. Churchill suggested “a meeting between us three at Invergordon…where the King could entertain, or at Balmoral.” Roosevelt responded he was “rather keen about the idea of Invergordon or a spot on the West coast of Scotland.” Yalta, however, turned out to be the chosen—and highly disappointing—destination in February 1945.21

The death of King George VI in 1952 was a severe blow for Churchill. Not only had he and the King served closely together throughout the war, they had become friends.22 Churchill wrote a note saying “For Valour” that was placed on the King’s coffin.

Elizabeth II

The child that Churchill so rightly described in 1928 now became Queen with Churchill, in his late seventies, as her first prime minister. Churchill’s youngest daughter Mary later told her daughter Emma Soames: “The Queen very quickly captivated him, he fell under her spell. I think he felt early on her immense sense of duty, and he looked forward to his Tuesday afternoon meetings with the young monarch.”23

Churchill’s official commitments in 1952 kept him away from the new Queen for much of the year. Lord Moran recorded in his diary on 30 September that Churchill was back from a holiday to the south of France and declared, “I am going to Balmoral tomorrow. I felt I ought to see the Queen. I have not seen her for two months.”24

Churchill flew north to Scotland in September to be the Queen’s guest at Balmoral. While there, news reached Downing Street that Britain’s first atom bomb had been successfully detonated on 3 October at Montebello Island, off the northwest coast of Australia (see FH 195). The Prime Minister’s fairly new private secretary, Anthony Montague Browne, was advised to call and wake Churchill to impart the news, “but even at this early stage,” he recalled, “I concluded this would be imprudent!”25

Apart from the historical consequences of the visit, there survives a rare colour film made of Churchill and Clementine on the banks of Loch Muick, on the Balmoral Estate, with the Royal Family that preserves a private moment. The Prime Minister can be seen playing with a piece of driftwood while a three-year-old Prince Charles stands close by.26 After the visit, Churchill wrote the Queen, “I was keenly impressed by the development of Prince Charles as a personality. He is young to think so much.”27 As he had with our new King’s mother, Churchill identified hidden depths in the future monarch from an early age.

Soon after the coronation of Elizabeth II, Churchill suffered a severe stroke at Downing Street on 23 June 1953. After a month of recovery at Chartwell, he met the Queen for the first time since his attack. She invited her Prime Minister and Clementine to Balmoral. Clementine, however, protested that the long Royal Train journey would undermine her husband’s recovery. Churchill’s doctor, Lord Moran, said to the patient: “The crux is, can you finish the journey?”28 Clementine believed not and wrote Winston: “you are improving steadily…but rather you must husband your strength.”

Typically, Churchill rose to the challenge and left for Scotland on 11 September. Not only did he survive the journey, he felt fresh and encouraged when he returned home.29 “I went to Church at Balmoral,” he wrote. “It is forty-five years since I was there. Now there were long avenues of people, and they raised their hands, waving and cheering, which I was told had never happened before.”30

Churchill later wrote to the Queen, “I must express to Yr. Majesty the keen pleasure which my wife and I derived from our Northern journey.…Balmoral was indeed a happy scene of youth and joy.” He was, however, exhausted by the excursions. The Queen subsequently wrote and included a photograph of the trip.31

Winston Churchill’s ties with the Royal Family are many and plentiful across political, social, and ancestral spheres. All of the anecdotes, history, and individual personalities would take a lifetime to chart. As the nation and the Commonwealth mourn the loss of our late Queen, we can all take comfort that Her Majesty and her first Prime Minister are about to resume their Audience after many long years.

Endnotes

1. David Torrance, “How Is a Prime Minister Appointed?” House of Commons Library, https://commonslibrary. parliament.uk/how-is-a-primeminister-appointed/, accessed 9 September 2022.

2. Victor Mallet, Life with Queen Victoria: Marie Mallet’s Letters from Court 1887–1901 (London: John Murray, 1968), p. Xxiv.

3. Richard Aldous, The Lion and the Unicorn: Gladstone versus Disraeli (London: Pimlico, 2007), p. 259.

4. Helen Rappaport, Queen Victoria: A Biographical Companion (ABC-CLIO biographical companions, 2003), ABC-CLIO Interactive, p. 55.

5. Winston S. Churchill, My Early Life: A Roving Commission (New York: Scribner, 1930), pp. 268–69.

6. Roy Jenkins, Churchill (London: Pan Books 2002), p. 237.

7. Randolph S. Churchill, Winston S. Churchill, vol. II, Young Statesman, 1901–1914 (London: Heinemann, 1966), pp. 52–53.

8. Ibid., p. 67.

9. Richard Hough, Winston and Clementine: The Triumph of the Churchills (London: Bantam, 1991), p. 22.

10. Mary Soames, ed., Speaking for Themselves: The Personal Letters of Winston and Clementine Churchill (London: Black Swan, 1999), p. 55.

11. David Lough, No More Champagne: Churchill and His Money (Rearsby, Leicester: W. F. Howes Ltd, 2016), p. 98.

12. Hough, p. 223.

13. Mary Soames, Clementine Churchill (London: Transworld, 2002), pp. 98–99.

14. Churchill, Young Statesman, pp. 474–75.

15. Jenkins, p. 237.

16. Soames, Speaking for Themselves, p. 76.

17. Ibid., p. 328.

18. Ibid., p. 329.

19. Robert Rhodes James, A Spirit Undaunted: The Political Role of George VI (London: Abacus, 1999), p. 234.

20. Cita Stelzer, Dinner with Churchill: Policy-Making at the Dinner Table (New York: Pegasus Books, 2013), p. 224.

21. Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, vol. VII, Road to Victory, 1941–1945 (Toronto: Stoddart, 1986), p. 852.

22. Kenneth Weisbrode, Churchill and the King: The Wartime Alliance of Winston Churchill and George VI (New York: Penguin, 2015), p. 183.

23. Emma Soames, As Churchills We’re Proud To Do Our Duty, https://winstonchurchill.org/ publications/churchill-bulletin/bulletin-048-jun-2012/emmasoames-in-the-telegraph-aschurchills-were-proud-to-do-ourduty/, accessed 9 September 2022.

24. Charles Moran, Churchill: The Struggle for Survival 1945–60 (London: Robinson, 2006), p. 102.

25. Martin Gilbert, Churchill: A Life (London: Minerva, 1992), p. 908.

26. https://www.flickr.com/photos/hillview7/15480803138, accessed 9 September 2022.

27. Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, vol. VIII, Never Despair, 1945–1965 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1988), p. 764.

28. Moran, p. 179.

29. Jenkins, p. 867.

30. Moran, p. 192.

31. Gilbert, Never Despair, pp. 886–87.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.