Genealogy

Churchill and His Jerome Relations

Leonard Walter Jerome, American financier from New York, and the maternal grandfather of Winston Churchill. 3 November 1817 to 3 March 1891

February 12, 2009

When Heroes Were Ubiquitous

James Jerome of the 10th Mountain Division

“One of the greatest of causes is being fought out, as fought out it will be, to the end. This is indeed the grand heroic period of our history, and the light of glory shines on all.” -WSC, 27 April 1941

BY JUDY BARRETT LITOFF

Finest Hour 113

In February 1945 at Yalta in the Crimea, Winston Churchill met with Franklin Roosevelt and Josef Stalin to plan for the postwar world. As Churchill pressed for free elections in Poland and the establishment of democratic governments in other liberated nations, his young American cousin, 21-year old Staff Sergeant James Colgate Jerome of Bennington, Vermont, made history of another sort as he fought with the famous 10th Mountain Division in the Apennine Mountains of northern Italy.

2025 International Churchill Conference

James Jerome, second son of William Travers Jerome, Jr. and Hope Colgate Jerome, was born on 23 January 1924 in Yonkers, New York. His great grandfather, Lawrence Jerome (1820-1888), and Churchill’s grandfather, Leonard Jerome (1818-1891), were brothers, well-known for their financial prowess, and for making and losing several fortunes on Wall Street. Lawrence and Leonard married sisters, Catherine and Clara Hall; Clara became the American grandmother of Winston Churchill. James’s grandfather, William Travers Jerome (1859-1934), the crusading New York district attorney who courageously stood up to Tammany Hall, was double first cousins with Jennie Jerome (1854-1921).

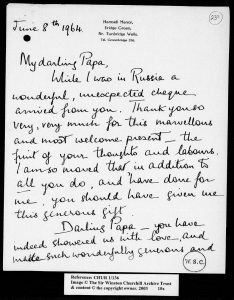

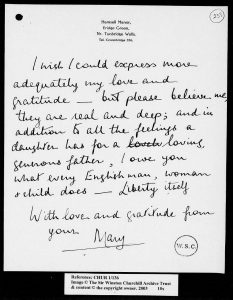

Winston Churchill followed the career of his American cousin with interest and admiration. He met William in the 1920s, but no record of their conversation survives. William’s son, William T. Jerome, Jr. (1890-1952), a distinguished Vermont lawyer and state’s attorney and a second cousin of Churchill, actually had a closer relationship with Churchill than his father. Whenever Churchill visited the United States, he always contacted Jerome, Jr., and their two wives, Clementine and Hope, were also good friends.

Two letters from Churchill to William Jerome, Jr. are known. The first, from Chartwell on 17 March 1934, expressed “profound sympathy on the loss of your Father….I knew him in the days when he was fighting so actively. He seemed to me to be a Roman Figure, and I shall always preserve pleasant recollections of the dinner he gave me at the Club in New York.” The second letter, dashed off on 30 December 1943 from Marrakesh, Morocco, where Churchill was meeting with Montgomery and Eisenhower to plan the invasion of Europe, thanked Jerome, Jr. for writing to him, “as I am always interested to have news of my relations in America.”

By the time William Jr. received the letter from Marrakesh, his son, James Jerome, had served with the 10th Mountain Division for almost ten months. In April 1943, following his first semester at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, James had volunteered for the 10th because “I just thought I’d like the ski troops.”

He joined an elite group of 13,321 skiers, mountain climbers, and winter sports enthusiasts, including Charles McLane, captain of the Dartmouth ski team; Torger Tokle, the world’s greatest ski jumper; even veteran Finnish skiers of the Russo-Finnish war. Until June 1944, the Division trained at Camp Hale, Colorado, 9,200 feet high in the Rocky Mountains. They endured grueling maneuvers as they learned to ski, climb, and fight under the most brutal conditions. Carrying 90-pound packs, they prided themselves in their ability to ski across rugged terrain in sub-zero, blizzard conditions. Drifts of 40 to 50 feet of snow were common near the summit of the peaks.

Training under extreme conditions afforded the volunteers the opportunity to develop an unusually strong sense of camaraderie and friendship that would serve them well when they faced actual combat in the rugged mountains of northern Italy. On 22 June 1944, the 10th was transferred to Camp Swift, Texas, where it remained until December 1944, when it was relocated to Fort Henry, Virginia in preparation for shipment to northern Italy later that month. Arriving in Italy in early January, the Division made its way to the front lines in the Apennine Mountains by the middle of the month.

Under the command of World War I Medal of Honor recipient General George P. Hays, the Division was charged with overwhelming the German defense line along Riva Ridge and Monte Belvedere-Monte dellar Torracia Ridge. In American hands these positions would provide observation as far as the Po Valley, some 20 miles to the north. On three previous occasions, 5th Army units had unsuccessfully attempted the assault.

As darkness fell on the bitterly cold evening of February 18th, expert climbers from the 86th Mountain Infantry Regiment began the treacherous assault up the 1500-foot, almost perpendicular, cliff to the Riva Ridge. Their rigorous training at Camp Hale had prepared the men for just this type of action. German troops manning the ridge considered the cliff impossible to scale; they were unprepared for the attack and, despite waging three minor counterattacks, were driven out by that afternoon.

On February 19th troops from the 85th and 87th Regiments, including James Jerome, made a bayonet attack up the slopes of Monte Belvedere. Five days later Monte Belvedere and the surrounding peaks were firmly in American control. The Germans’ northern Italian stronghold had been broken – at a cost to the 10th of 903 casualties, of which 203 were killed.

Recalling those difficult days, James recently remarked, “That campaign was rough.” Then, remembering the war games in Colorado, he added that whenever the fighting got a little hard in Italy, the standard joke of men of the 10th was that it was “better than Camp Hale.”

Fighting continued northward along the ridge line during March. For his part, Staff Sergeant Jerome was awarded the Bronze Star for the “initiative, resourcefulness, and intelligent performance” that he demonstrated, which resulted in his battalion “beating off many counterattacks and inflicting heavy casualties on the enemy.”

The final phase of the war in Italy began on April 14th when the 10th Mountain Division spearheaded the 5th Army drive by leading the attack toward the Po Valley. Fighting was fierce and casualties heavy, but on April 23rd, the 10th was the first division to reach and cross the Po River. Over the next several days, they moved so rapidly that they sometimes got ahead of the enemy.

The Division’s final combat began on 27 April in the vicinity of Lake Garda, where it cut off the Germans as they attempted to escape to the Brenner Pass. On May 2nd, with advance units of the 10th moving northward through the Brenner, Nazi forces in Italy surrendered. In 114 days of combat, the 10th Mountain Division suffered 992 killed in action and 4,154 wounded. Among the dead was James’s boyhood friend and beloved cousin from Bennington, David Colgate Dennis.

The 10th Mountain Division destroyed five elite German divisions. General Hays called their assignment the most important and hazardous in Italy. General Mark Clark, Commanding General of the 5th Army in Italy, looked upon the action as “one of the most vital and brilliant in the [Italian] campaign.” But perhaps the greatest praise for the 10th came from Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, architect of the German defense, when he called the Division “outstandingly efficient.”

In July 1945, the 10th Mountain Division was sent back to America for 30 days of rest and relaxation. Plans called for the Division to be sent to the Pacific, but thankfully, the war ended with the dropping of the two atomic bombs in August, and James was spared a second round of combat.

After the war, James Jerome, like millions of other American veterans, took advantage of the G.I. Bill, using it to finance the completion of his education at Cornell, where he graduated with a B.S. degree in genetics from the College of Agriculture in 1949. Eventually James married, had three children, and became a successful dairy and cattle farmer in Bennington.

Not for some years did James Jerome begin to ponder the full significance of his relationship to his cousin Winston. As he has since said, he didn’t give Churchill much thought during the war because “when you’re young, in combat, and faced with unrelenting danger, you get pretty selfish in your thinking.”

At the beginning of Churchill’s second Premiership in October 1951, James happened to be traveling in England and Scotland to buy cattle for his farm in Vermont. When he learned the results of the election, he sent roses to Mrs. Churchill on behalf of the American Jeromes. Learning that his American cousin was in Britain, Churchill immediately extended an invitation to come to Chartwell. Unfortunately, James had to leave the next day on an air cargo plane to accompany his recently-purchased cattle back to America. However, the following year, James’s older brother, William T. Jerome, III, and his family did visit the Churchills at Chartwell.

James Colgate Jerome was the only Jerome cousin of Winston Churchill to participate in combat during World War II. James’s older brother William, who later became president of Bowling Green State University in Ohio, served stateside with Army Intelligence but did not see combat. James and William and their male descendants are the only American Jeromes to carry on the paternal family name of Churchill’s mother, Jennie Jerome. After retiring from the cattle and dairy business in the early 1980s, James Jerome, who still lives in Bennington, distributed his cherished Churchill mementos to his three children. Today, for example, a large charcoal drawing of Winston Churchill proudly hangs in the great room of James Colgate Jerome, Jr.’s meticulously restored 1768 farmhouse in Bennington, as a reminder to his son, James, III, of his famous Churchill relation.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.