Finest Hour 180

Churchill’s African Journey

September 5, 2018

Finest Hour 180, Spring 2018

Page 20

By Fred Glueckstein

Fred Glueckstein is a frequent contributor to Finest Hour and author of Churchill and Colonist II (2014).

On 9 December 1905, Prime Minister Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman sent Winston Churchill, MP for Manchester North West, a telegram at his house, 29 Belgrave Square: “Greatly obliged if you would come and see me here at six o’clock.”1 During their meeting, Campbell-Bannerman invited Churchill to join his Government as Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies. The offer was accepted.

On Churchill’s first evening as a junior member of the Government, he attended a party in London where he was introduced to Edward Marsh, a clerk in the West African Department of the Colonial Office:

“How do you do?” asked Marsh. “Which I must now say with great respect.”

“Why with great respect”? Churchill responded.

“Because you’re coming to rule over me at the Colonial Office,” Marsh replied.2

2025 International Churchill Conference

Churchill made enquiries about the Colonial Office clerk, and subsequently asked him to be his Private Secretary. Marsh accepted and would work for Churchill off and on in this capacity for almost three decades.

Lord Elgin and Churchill

As Under-Secretary at the Colonial Office, Churchill, then thirty-one, became deputy to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, the Earl of Elgin. With Elgin in the House of Lords, Churchill became the sole voice for the department in the Commons. “Churchill was opting for prominence and parliamentary opportunity rather than rank, a high-risk strategy,” wrote Roy Jenkins.3

Lord Elgin and Churchill were unlike each other in personality and manner. Soon Elgin witnessed his new Under-Secretary exercise his ambitions and his manner.4 In 1907, Churchill decided to tour British East Africa extensively during the autumn recess. It was said that “Lord Elgin was not slow to applaud.” A cartoon on 31 July 1907 in Punch shows the Colonial Secretary helping Churchill pack his clothing. Under the headline “Parting is Such Sweet Sorrow,” Lord Elgin has one hand holding shirts and the other on Churchill’s shoulder with the caption, “Well, my boy, you see I’m helping to get you off, I shall miss you terribly. You must be sure to have a good rest, and whatever you do, don’t hurry back!”5

Before travelling to British East Africa, Churchill and George Scrivings, his father’s former servant, spent a month on the continent of Europe. While there, Churchill attended French Army maneuvers. After leaving France, Churchill and Scrivings travelled through Vienna and Syracuse on the Ionian coast of Sicily.

From Syracuse, Churchill and Scrivings, now joined by Eddie Marsh, went by sea to Malta. Awaiting Churchill in Malta was Colonel Gordon Wilson, the husband of Churchill’s aunt Lady Sarah Churchill, and the Admiralty cruiser Venus. From Malta, the cruiser went to Cyprus.

After leaving Cyprus, the cruiser took Churchill and his party across the Eastern Mediterranean, through the Suez Canal, and into the Red Sea towards Aden. During the voyage, Churchill prepared six protracted memoranda that were sent back to the Colonial Office. In a letter to his mother, Churchill explained that his memoranda were “upon things I want to have done.”

Churchill’s memoranda provoked Sir Francis Hopwood, the senior civil servant at the Colonial Office, who wrote in strong terms about Churchill to Lord Elgin: “He is most tiresome to deal with and will, I fear, give trouble—as his father did—in any position to which he may be called. The restless energy, uncontrollable desire for notoriety and lack of moral perception make him an anxiety indeed,” wrote Hopwood.6

Kenya

After stopping in the Somaliland Protectorate to educate himself on its affairs, Churchill and his party reached Mombasa on the coast of Kenya on 28 October 1907. Upon arrival, Churchill was met by the colony’s officials and received deputations from planters and local communities. While in Mombasa, Churchill was given a certificate by the colony’s governor that read: “The Rt Honorable Winston Churchill & party are granted a complimentary license to shoot such game as is allowed by the schedule of the game Regulations, during his tour through East Africa.”7

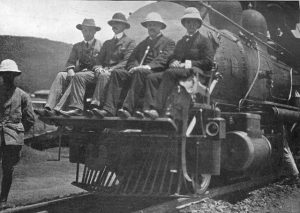

After two days of functions, inspections, and speeches in Mombasa, Churchill boarded a special train at his disposal from the Uganda Railway, which linked the interiors of Kenya and Uganda at Mombasa. “We sat (Gordon and I) on the engine [known as the Cow-catcher, it is an inclined frame on the front of a railroad locomotive] with our rifles, & as soon as we saw anything to shoot at—a wave of the hand brought the train to a standstill & sometimes we tried at antelope without even getting down. From the railway one can see literally every animal in the Zoo. Zebras, lions, rhinoceros, antelopes of every kind, ostriches, giraffes—on their day—& often five or six different kinds are in sight at the same moment,” wrote Churchill to his mother.8

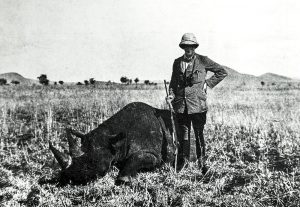

On the first day in the field, Churchill killed one zebra, one wildebeeste, two hartebeeste, one gazelle, and one bustard (a giant bird). For Churchill, the third day was momentous as he saw a rhinoceros grazing. “I cannot describe to you the impression produced on the mind by the sight of the grim black silhouette of this mighty beast—a survival of prehistoric times—roaming about the plain as he & his forerunners had done since the dawn of the world. It was like being transported back into the stone age.”9

Soon two more rhinoceros were sighted resting under a tree. Churchill, Marsh, and Gordon sneaked under the crest of the plateau to within 150 yards of the two new rhino. Churchill fired and hit the larger animal.

“She swerved round & came straight for us at that curious brisk trot which is nearly as fast as a horse’s gallop, & full of surprising activity. Everybody fired & both the rhino turned off—much to our relief,” wrote Churchill, “and then in a few more seconds down came the big one on the ground & the smaller one managed to get away under a heavy fire—this one we followed up & killed later in the day. I must say I found it exciting and also anxious work.”10

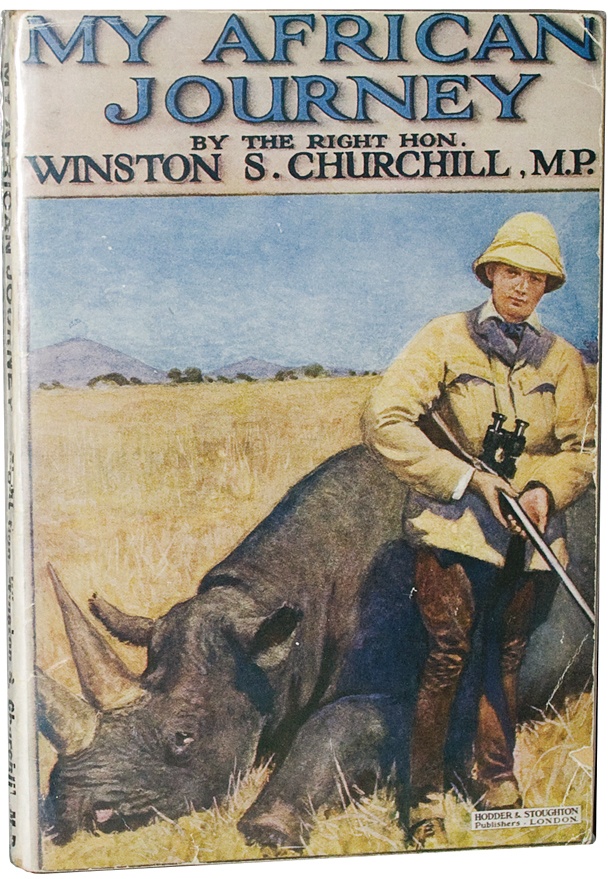

While in Africa, Churchill received an offer from The Strand Magazine for five articles on his travels for £150 each. He gratefully accepted, since it would “definitely liquidate all possible expenses in this journey.” Churchill would also receive an additional £500 for the book rights to his account of his travels in Africa, which was published as My African Journey.

On 5 November 1907 at Thika, Churchill spent time hunting lions without success. That evening, he proceeded to Nairobi, where he dined with the Governor. From Nairobi, Churchill could see Mount Kenya with its snowclad peak.

Uganda

While in Nairobi, Churchill visited Fort Hall and Embu. From there, he proceeded from Nairobi to Elmenteita for pig-sticking with Lord Delamere. Churchill, Marsh, Scrivings, and Wilson then arrived at Kisumu, where they were greeted by hundreds of members of the unclothed Kavirondo tribe. From Kisumu on Lake Victoria, Churchill and his party went by boat on to Entebbe and then travelled by rickshaw to Kampala.

In Kampala, Churchill “was delighted to hear the little black school boys in white English cotton clothes singing Oh dear, what can the matter be? This seemed to please him almost more than anything else in East Africa, apart from the highly-coloured butterflies,” Ronald Hyman later concluded.11

Churchill then took a steamboat to Ripon Falls on the Victoria Nile. On 23 November 1907, he went on trek, also referred to as safari, where he traveled on foot, by bicycle, and canoe from camp to camp. Churchill coined a memorable phrase after each day’s trek: “sofari, sogoody.”12

Churchill’s party then reached Jinja, where the Nile leaves Lake Victoria and begins a 4,000 mile journey to the sea. From Jinja, Churchill, Wilson, Marsh, and Scrivings continued north through the Uganda Protectorate. After touring Uganda, Churchill and his party spent ten days on a steamer to reach the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.

Death of George Scrivings

On 23 December 1907, Churchill and his companions were at Khartoum in Sudan. That day, Churchill’s faithful servant Scrivings fell ill with choleric diarrhea. After sixteen hours, he died on Christmas Eve. “Scrivings’ death was a great shock to me,” Churchill wrote his brother Jack, “& has cast a gloom over all the memories of this pleasant & even wonderful journey. We all must have eaten the same dish which contained the poison—whether it was a tin of ptomaine-poisoned fish, or rotten asparagus, or what, will never be known.”13 It was only Churchill’s stronger constitution that prevented him from meeting Scriving’s tragic fate.

Churchill arranged the funeral. On Christmas, Scrivings was buried in the Khartoum Cemetery in the evening with full military honors, since he had been a Yeoman. “The Dublin Fusiliers sent their band and a company of men, and we all walked in procession to the cemetery as mourners, while the sun sank over the desert, and the band played that beautiful funeral march you know so well,” Churchill wrote Jack.14

Afterwards, Churchill wrote a heart-rending letter from Khartoum to Scrivings’ wife. After telling her what occurred, Churchill wrote: “My heart bleeds for you and for your children. It will be my duty to make adequate provision for your future and theirs; & you need not worry on these matters. We will talk of them when I return…. My own sorrow is keen & deep. I was very fond of Scrivings & regarded him as a faithful friend, whose character and virtues I respected and admired. May God help you to bear your loss.”15

The loss of Scrivings had a deep effect on Churchill. In his book My African Journey, Churchill wrote: “Africa always claims its forfeits; and so the four white men who had started together from Mombasa returned but three to Cairo. A military interment involves the union of the two most impressive rituals in the world. The day after the Battle of Omdurman it fell to my lot to bury those soldiers of the 21st Lancers, who had died of their wounds during the night.”

Churchill continued: “Now after nine years, in very different circumstances, from the other end of Africa, I had come back to this grim place where so much blood has been shed, and again I found myself standing at an open grave, while the yellow glare of the departed sun still lingered over the desert, and the sound of funeral volleys broke its silence.”16

The remainder of the journey to British East Africa soon came to an end. Churchill, Marsh, and Wilson travelled to Upper Egypt, back to Cairo, then Alexandria. On 17 January 1908, Churchill returned to London after an absence of five months.

For Churchill, the trip to British East Africa was a combination of conducting colonial administration business, big-game hunting, and sightseeing. He never forgot his travels and considered his journey through British East Africa one of his greatest adventures, though sadly marred by the loss of his faithful servant

George Scrivings.

Endnotes

1. Randolph S. Churchill, The Churchill Documents, Volume 3, Early Years in Politics 1901–1907 (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 2007), p. 411.

2. Martin Gilbert, Churchill: A Life (London: Pimlico, 1991), p. 174.

3. Roy Jenkins, Churchill: A Biography (New York: Plume, 2002), p. 105.

4. Martin Gilbert wrote of the difference between Elgin and Churchill: “Throughout his time at the Colonial Office, Churchill endeavoured to instill Liberal principles into Colonial administration. His minutes to Elgin were so outspoken that in several cases Elgin asked him to paste them over so that junior officials would not see them.” Gilbert, pp. 182–83.

5. Ronald Hyman, Elgin and Churchill at the Colonial Office 1905–1908 (New York: Macmillan, 1968), p. 369.

6. Gilbert, p. 186.

7. Randolph S. Churchill, The Churchill Documents, Volume 4, Minister of the Crown (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 2007), p. 692.

8. Ibid., pp. 692–93.

9. Randolph S. Churchill, Winston S. Churchill, Volume II, Young Statesman 1901–1914 (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 2007), p. 231.

10. Ibid., p. 232.

11. Hyman, p. 356.

12. Ibid.

13. Gilbert, p. 189.

14. Churchill, Young Statesman, p. 236.

15. DailyMail.com. Posted 28 September 2016. http://www. dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3811344/Winston-Churchillescaped-bout-food-poisoning-killed-servant-trip-East-Africa. html.

16. Winston S. Churchill, My African Journey (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1990), p. 124. First published by Hodder and Stoughton, 1908.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.