Finest Hour 166

Churchill’s Final Farewell: The State and Private Funeral of Sir Winston Churchill

July 24, 2015

Finest Hour 166, Winter 2015

Page 09

By Rodney Croft

In commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of Churchill’s death, Mr. Rodney Croft has written the first book to focus exclusively on the State and Private Funeral of Sir Winston Churchill. The book is available either in electronic or print-on-demand format. Mr. Croft has kindly permitted Finest Hour to publish the following extracts.

MV Havengore bore Churchill’s coffin up the River ThamesHer Majesty The Queen made her wish known after her Coronation in 1953 that Winston Churchill should be afforded a State Funeral. In the United Kingdom, a State Funeral traditionally refers to that of a Monarch. Such funerals had, however, been held for commoners in the past, including those for the two Pitts (1778 and 1806), Lord Nelson (1806), The Duke of Wellington (1852), William Gladstone (1898), and The Earl Roberts (1914).

MV Havengore bore Churchill’s coffin up the River ThamesHer Majesty The Queen made her wish known after her Coronation in 1953 that Winston Churchill should be afforded a State Funeral. In the United Kingdom, a State Funeral traditionally refers to that of a Monarch. Such funerals had, however, been held for commoners in the past, including those for the two Pitts (1778 and 1806), Lord Nelson (1806), The Duke of Wellington (1852), William Gladstone (1898), and The Earl Roberts (1914).

2025 International Churchill Conference

The Arrangements

The Duke of Norfolk, hereditary Earl Marshal of England, is responsible for arranging all state occasions. It therefore fell to him to make the necessary arrangements for Churchill’s funeral. The operation became known as “Hope Not.”

The codename turned out to be apt, because Churchill survived for years. The final version of Hope Not was dated 24 January 1965, the day Churchill died. Plans were immensely detailed, even down to where honour guards would be able to obtain buns and hot drinks. The troops involved totaled 575 Officers and 6508 Other Ranks, which, for a commoner, were numbers last seen for The Duke of Wellington’s State Funeral in 1852, on whose funeral Churchill’s was based.

There were also elaborate plans drawn up by the Metropolitan Police. A document, Operation Order No 801, concerning traffic arrangements was 59 pages long and printed on a size of paper normally reserved for Royal occasions.

Churchill’s original wish as stated in early copies of his will was to be cremated and his ashes buried in the grounds of Chartwell. However, towards the end of 1959 it became known that he had visited St. Martin’s Church in Bladon, Oxfordshire, in view of Blenheim Palace, where he was born and where in the churchyard other members of his family were buried. It is said that Churchill tapped an empty plot with his walking cane and remarked: “This is my place here.” Churchill’s will was then changed accordingly.

The nearest station to the village of Bladon was Long Hanborough on the Western Railway line from Paddington. The story told to Sir Alec Bedser by the Duke of Norfolk was that after Churchill had decided to be buried at Bladon, the VIP guest list was being discussed between the two of them. When Norfolk came to Charles de Gaulle, Churchill insisted that he did not wish the French President to attend his funeral. Churchill still remembered the difficult times he had experienced with de Gaulle during the war years despite subsequent rapprochement.

Norfolk apparently pleaded with Churchill that in the interests of Entente Cordiale and the UK’s wish to join the European Economic Community, de Gaulle should be invited. Eventually Churchill acquiesced but on the condition that his funeral train would leave from Waterloo, not Paddington. Waterloo was on the Southern Railway line. However, there was a disused spur at Reading which linked the Southern Railway to the Western. It was known in railway circles that Churchill knew of the spur and therefore understood the journey by rail to Long Hanborough from Waterloo was possible.

In 1964 Lady Churchill, aware of her husband’s wish to be cremated, expressed the opinion that it might be better for Sir Winston’s body to be cremated before the lying-in-state. However, the decision was made to embalm Churchill’s body after his death to enable it to be in his coffin for the duration of the lying-in-state and funeral.

The Lying-in-State

Following Churchill’s death on the morning of Sunday, 24 January 1965, Operation Hope Not swung into action. A catafalque was built in Westminster Hall. It was covered with black velvet with a light yellow carpet over the pedestal. The floor of the cavernous hall was covered with a beige carpet to muffle the sound of people’s foot treads while filing past. The coffin was covered with the Union Flag, upon which was placed the insignia of the Most Noble Order of the Garter. There were no flowers, but there were six large candlesticks with candles around the catafalque.

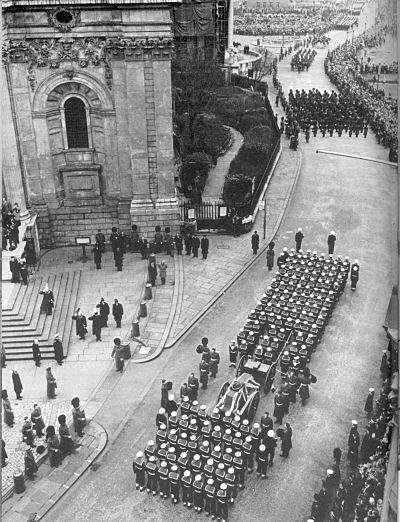

Winston Churchill’s coffin leaves St. Paul’s on 30 January 1965.There were five watch officers, one placed at each corner of the catafalque and one on the steps overlooking it, all with heads bowed, their hands resting on their unsheathed swords. The duration of each watch was twenty minutes after which the watch was changed. Early on the first day, the watch was taken over by Admiral of the Fleet, The Earl Mountbatten of Burma and the Defence Chiefs of Staff.

Winston Churchill’s coffin leaves St. Paul’s on 30 January 1965.There were five watch officers, one placed at each corner of the catafalque and one on the steps overlooking it, all with heads bowed, their hands resting on their unsheathed swords. The duration of each watch was twenty minutes after which the watch was changed. Early on the first day, the watch was taken over by Admiral of the Fleet, The Earl Mountbatten of Burma and the Defence Chiefs of Staff.

The Lying-in-State lasted from Wednesday, 27 January to 6 am on 30 January. During this period, Westminster Hall was open twenty-three hours a day and closed just for one hour for cleaning and vacuuming the carpets.

Over three and a half days, the queue reached three miles in length, and 4,000 people slowly filed past Churchill’s body every hour. The final total of those who paid their last respects was 321,360.

The Procession

The procession from Westminster Hall to St. Paul’s Cathedral for the service on Saturday, 30 January stepped off at 9:45 am and involved 7,000 military personnel. Half a million people lined the route.

The chief mourners walking behind the Naval Gun Carriage that bore Churchill’s coffin were the male members of the Churchill family and Anthony Montague Browne, Churchill’s Private Secretary.

Randolph Churchill, Sir Winston’s son, had undergone an operation for removal of part of his left lung the previous year. Randolph’s own son, Winston, was concerned his father would not be able to make the twomile walk particularly up Ludgate Hill, but Randolph succeeded in his own inimitable and reverent style.

St. Paul’s

At St Paul’s, the bearer party made up of eight members of the Grenadier Guards was met by the Lord Mayor of The City of London and the Ceremonial Pallbearers: Field Marshal the Earl Alexander of Tunis, The Earl Attlee, The Earl of Avon, The Lord Bridges, The Lord Ismay, Mr. Harold Macmillan, Admiral of the Fleet The Earl Mountbatten of Burma, The Lord Normanbrook, Marshal of the RAF The Viscount Portal of Hungerford, Field Marshal The Viscount Slim, Field Marshal Sir Gerald Templer, and Sir Robert Menzies.

The English oak, lead-lined coffin weighed a quarter of a ton, an immense load for the bearer party to carry up the steps of St. Paul’s. They had rehearsed this part on a dozen occasions, but on the second flight of steps a problem arose. The ceremonial pallbearers had walked down the steps from the Cathedral entrance to greet Churchill’s coffin at the forecourt level and escort it into St. Paul’s. Lord Attlee, now a fragile 82-year-old and one of the ceremonial bearers, paused in returning up the second flight. The Grenadiers therefore had to hesitate. The weight of the coffin shifted back on those behind, particularly the last two bearers, causing an enormous strain; but the Grenadiers held fast.

At 10:49 am the coffin was carried into the Cathedral and placed on the bier under the Dome.

The congregation numbered 3000. In addition to the Royal Family and the Churchills, there were leaders of over 100 countries in attendance, including nearly every reigning monarch of Europe. President Lyndon Johnson, recovering from hospitalization, could not attend, but former President Eisenhower, Churchill’s wartime colleague, made the journey.

Churchill had wished for the service to have as its main theme Anglo-American unity and for there to be vigorous hymns. During the singing of the Battle Hymn of the Republic, on an otherwise dark grey and bitterly cold winter day, a shaft of bright sunlight shone down through the dome onto Churchill’s coffin, such a poignant moment it caused shivers down spines.

The Thames

From St. Paul’s the body was transported to Tower Pier. As the coffin was carried onto MV Havengore by the Grenadiers, Churchill was piped aboard by the Royal Naval Piping Party. At her stern Havengore carried the flag of the Port of London Authority.

As Havengore motored up the Thames, General Eisenhower read his tribute to Winston Churchill on the BBC televised broadcast.

The arrival at Festival Pier coincided with the flood tide, so the deck of Havengore was as level as possible with the jetty to facilitate the transfer of Churchill’s coffin ashore. No doubt the timing of the flood tide had been pivotal to all the timings of the day. The Grenadiers placed the coffin in a motor hearse for the short journey to the concourse of Waterloo station.

The Railway Journey

The hearse slowly drove from Festival Pier past the famous red lion at Waterloo station and onto the concourse where it was greeted by the new bearer party from the Queen’s Royal Irish Hussars, an amalgamation of the 4th Queen’s Own Hussars and 8th King’s Royal Irish Hussars, the former being Churchill’s regiment when he entered the Army in 1895.

Churchill’s funeral train consisted of the Pacific steam locomotive Battle of Britain Class, Winston Churchill No. 34051 and six Pullman Cars. The bearer party carried Churchill’s coffin up a short ramp into the bogie van and placed and secured it on the bier. Two of the bearers remained on guard in the bogie van during the duration of the 125-minute, 72-mile journey.

At 1:28 pm, following a signal from the Station Master, the train slowly and quietly steamed out of platform 11. On the front of the locomotive were three large white discs. The “V” formation used usually signaled a breakdown train, but on this occasion it represented Churchill’s famous “V” for Victory sign.

On the line from Waterloo to Long Hanborough, stations opened along the route so people could pay their respects as the train pulled through. The platforms were packed with people, the men removing their hats in respect. There were other touching sights of people and individuals paying their last respects: the single farmer with his dog standing to attention in a field, cap in hand; farmers with their children on ponies all standing quietly; the lock keeper standing to attention by his lock; the retired RAF officer standing and saluting on the flat roof of his house in his old uniform.

The train arrived at Long Hanborough at 3:23 pm. The small and somewhat dilapidated station where the German Kaiser had been on a visit to Blenheim many years before had been smartened up with carefully placed linen drapes covering tired and flaking paintwork.

Bladon

The short journey to St. Martin’s Church at Bladon was two miles. By family request, the roadsides were empty of people. The village had been spruced up with buildings having been given a coat of paint. Outside one of the pubs, six telephone boxes had been placed to accommodate the world’s press.

The funeral party was met by the Rector of St. Martin’s. Churchill’s coffin was taken straight to the graveside, where a short committal service took place.

It is traditional in the churches of Western Christianity to bury a coffin with the head facing the East. However, the coffin was discovered to be too wide to be lowered into the grave that had been dug. So it was turned round where the grave was fortunately found to be wider and then gently lowered. Thus, Churchill appropriately faces westwards towards his greatest ally the United States and to his mother Jennie’s homeland.

Rodney J. Croft is a semi-retired vascular surgeon and Dean of Clinical Studies UK for St. George’s University. A Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, he lives near Churchill’s old constituency of Woodford.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.