Finest Hour 188

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – Turning Point

September 1, 2020

Finest Hour 188, Second Quarter 2020

Page 45

Review by John Campbell

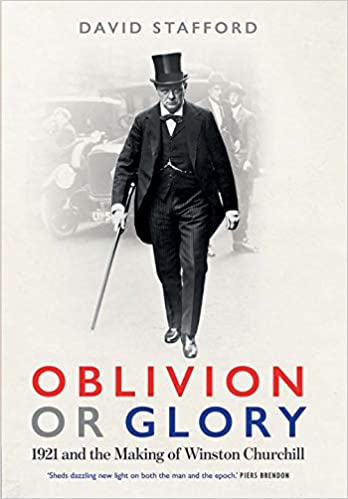

David Stafford, Oblivion or Glory: 1921 and the Making of Winston Churchill, Yale University Press, 2019, 301 pages, $26/£20. ISBN 978–0300234046

John Campbell’s books include major biographies of F. E. Smith, Aneurin Bevan, Edward Heath, Margaret Thatcher, and Roy Jenkins.

Every time I review a book for Finest Hour I am amazed by how many new angles historians manage to find from which to write about Churchill. Some do seem to be scraping the barrel; but, by focussing closely on a single critical year in Churchill’s life, David Stafford has found a genuinely illuminating and fresh perspective. One could suggest other pivotal years, but Professor Stafford makes a compelling case for 1921 as the year in which Churchill, on the cusp of middle age at forty-six, began to bounce back from the disaster of the Dardanelles, shake off his youthful reputation for recklessness and poor judgment, and be recognised, in some quarters at least, as a potential Prime Minister.

Much of the freshness comes from the way Stafford mixes the public and political with the private and personal, with no clear boundary between the two. His book opens with Churchill at a New Year party at Philip Sassoon’s house at Port Lympne, along with Lloyd George and various other ministers and fixers, where the singing of music hall songs mingled with serious discussion; and ends with Winston and Clementine enjoying Christmas on the Riviera. In between, a constant whirl of country house weekends with aristocratic relatives and society hostesses is a reminder, often lacking in conventional political history, of the gilded social world in which the governing class of the day lived and moved. By contrast, Churchill only once visited his Dundee constituency during the year and was shocked by the poverty and barefoot children he encountered.

2024 International Churchill Conference

Wherever he went, even while attending important conferences, Churchill would disappear for whole afternoons to indulge his recently discovered passion for painting. At Jerusalem in March he seemed to one of his aides to “grudge every moment spent away from his easel.” Painting, he confessed, was “the joy of my life.” Yet he also found time in 1921 to write the first volume of his memoir The World Crisis, for which he negotiated enormous British, Empire, and American advances. His previously perilous finances were further transformed by a timely inheritance from a childless Irish cousin killed in a train crash, so that by the end of the year he was in a position to buy the country house he had long craved, Chartwell. But it was a year of grief as well. In June his mother Jennie died after a fall; and in August his youngest daughter Marigold—the “Duckadilly”— died of septicaemia, just short of her third birthday.

Amid all this, Churchill turned his political career around. In January, Lloyd George moved him from the War Office, where he had been responsible for demobilising the troops after the Armistice, to the Colonial Office, which included the new British mandates in Mesopotamia and Palestine: a can of worms which he was initially reluctant to accept. In March he was bitterly disappointed not to be made Chancellor. But with typical resilience he threw himself into trying to reshape the Middle East. He chaired a three-week conference in Cairo—lots of opportunity for painting—during which he created the new kingdom of Iraq and installed T. E. Lawrence’s guerrilla ally Faisal as its king over the opposition of the French; he inaugurated—largely to save money—the controversial policy of using the RAF to police the territory from the air; and strove unsuccessfully to reconcile the contradictory promises of the Balfour Declaration by persuading the Jews and Palestinians to talk to each other.

Lord Curzon, the Foreign Secretary, complained that Churchill was trying to be “a sort of Asiatic Foreign Secretary.” But Churchill was not content to be confined to Asia. When Curzon charged that it was “entirely wrong that the Colonial Secretary…should air his Independent views on an F.O. question,” Churchill retorted that “There is no comparison between these vital foreign matters [which] affect the whole future of the world and the mere departmental topics with [which] the Colonial Office is concerned. In these matters we must be allowed to have opinions”; and opinions he certainly had.

Churchill made major speeches calling for revision of the Treaty of Versailles to reconcile France and Germany, presciently anticipating the rise of Nazism. “Let it be the part of Britain,” he urged, “to mitigate the dangerous poisons still rife in Europe.” And already he was promoting the centrality of Britain’s relationship with the United States, “for it is in the unity of the English-speaking peoples that the brightest hopes for the progress of mankind will be found to reside.” Stafford suggests that Churchill was always more interested in the transatlantic relationship than he ever was in the empire. Despite his reputation as an imperialist, Churchill never actually visited India or South Africa after 1900.

At the end of the year Churchill also played a key role in negotiating the Downing Street treaty that gave independence to southern Ireland. This he did by striking up an unlikely relationship with IRA commander Michael Collins. Churchill’s one serious lapse of judgment was in continuing to back the anti-Bolshevik forces in Russia, which by 1921 were a lost cause. He relied, as he would continue to do up to 1940, on his private sources of intelligence such as Desmond Morton and Edward Spears; but in this case they let him down. Nevertheless the newspapers were beginning to praise his “statesmanship.” One political sketch writer noted that for all his faults he spoke “with the precision and authority of a keen and genuinely independent mind.” Another thought him “the only man in the Cabinet with a sane and comprehensive view of world politics.” By the end of the year Churchill was close to fulfilling Edward Grey’s pre-war prediction that “Winston, very soon, will become incapable from sheer activity of mind of being anything in Cabinet but Prime Minister.” It would still take twenty years and another war, but the qualities he then displayed were already fully formed in 1921.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.