Finest Hour 187

The Queen’s Own Oxfordshire Hussars and Blenheim

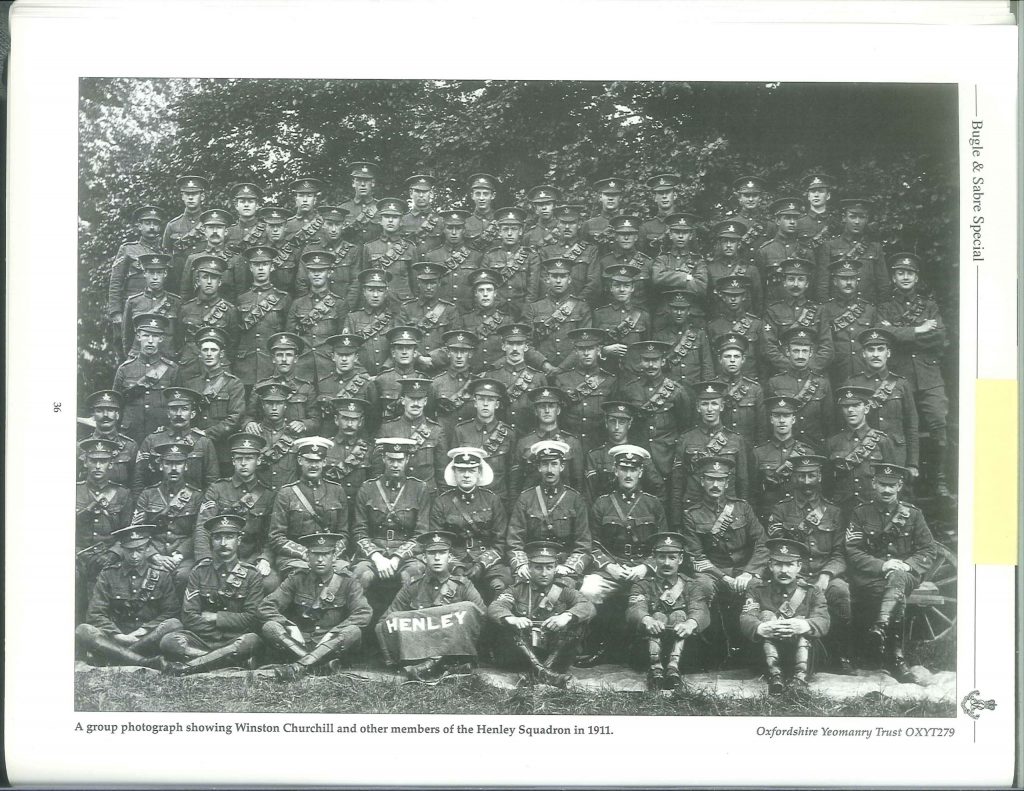

Churchill with his squadron of the Queen's Own Oxfordshire Hussars

July 22, 2020

Finest Hour 187, First Quarter 2020

Page 22

By Douglas S. Russell

Douglas Russell is author of Winston S. Churchill: Soldier, The Military Life of a Gentleman at War (2005).

From the time of the first Duke of Marlborough (1650–1722) each succeeding generation of Spencers, Churchills, and Marlboroughs was active in the military service of Great Britain, and Blenheim Palace has been a part of that tradition. Each duke from the first in the seventeenth century to the eleventh in the twenty-first century held an officer’s commission.

The Spencer-Churchill family began its long and active role in the Oxford Yeomanry in 1803 when Lord Francis Spencer, brother of the fifth duke, raised the Woodstock squadron of cavalry only five years after the regiment was formed.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the Oxford Yeomanry had reached regimental strength and was one of thirty-eight Imperial Yeomanry cavalry units. It was known as the Queen’s Own Oxfordshire Hussars, a title granted by Queen Adelaide—the wife of King William IV—in 1835. Commonly referred to as the Q.O.O.H., the regiment was organized in four squadrons located at Henley, Oxford, Woodstock, and Banbury, with its headquarters at Oxford.

2024 International Churchill Conference

An account written in 1910 listed the strength of the regiment at twenty-two officers and 396 other ranks. “The regiment had acquired a well-merited reputation for smartness, horsemanship, and horses, the horses being the object of repeated eulogy: unquestionably the high degree of efficiency to which the Queen’s Own has attained is due in great measure to the number of ex-cavalry officers who have either commanded or held other commissions in it.”1 The officers and men provided their own horses, and the regiment was sometimes referred to as “the agricultural cavalry” because most of its ranks came from the farming sector of the county. By 1910 the regiment was part of a cavalry brigade that included yeomanry cavalry units from Berkshire and Buckinghamshire.

An Oxfordshire hussar cut a very dashing figure in the full dress uniform. It featured a navy blue tunic with elaborate silver braid on the chest, sleeves, and collar with mantua purple facings.

The trousers were of mantua purple with a single silver stripe on each leg and silver braid on the front above the knees. The black fur busby hat was ornamented with a silver-trimmed purple busby bag, and a silver boss-and-chin strap. The busby plume was made of short purple vulture feathers at the base and fifteen-inch-tall, white ostrich feathers at the top. It was said one cavalryman could tell the regiment of another at long distance from their distinctive plumes. The uniform was worn with highly polished Hessian-style boots, which had pink heels that helped present a grand appearance for parades, levees, and balls.

Major Churchill

As a reserve regiment, the Q.O.O.H. were often granted permission by the several generations of Dukes of Marlborough to conduct drills and military exercises on the extensive grounds of the Blenheim estate. Winston S. Churchill was born at Blenheim Palace and was often there for visits from an early age. Thus, as a youth, he often witnessed the summer cavalry training camps in which he would participate as a grown man.

Following his four and a half years as a cavalry lieutenant in the British Army with active service in Cuba, India, Sudan, and South Africa, Churchill left the army in 1900 to pursue his career in politics. Always maintaining an interest in military matters and a love of horses and uniforms, he soon sought a commission in the army reserves. It is not surprising that he decided to join the Oxfordshire Hussars, his home county regiment, with which the Churchills had close ties.

The first listing of Churchill on the rolls of the Q.O.O.H. places him in the Woodstock squadron, which was commanded by his cousin “Sunny,” the Ninth Duke of Marlborough, who was a major. Winston’s brother Jack held a lieutenant’s commission. The three of them had served together in South Africa during the Second Boer War.

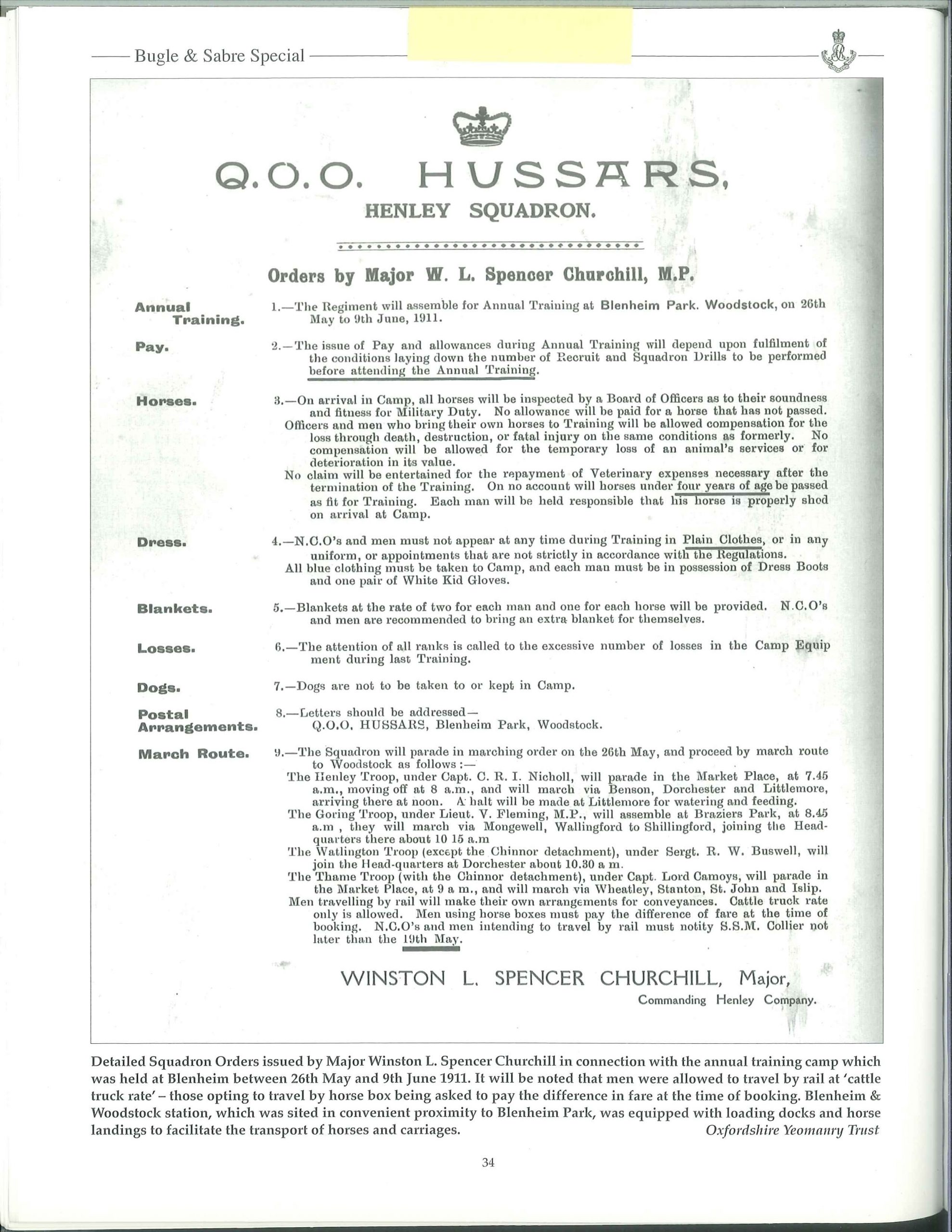

Winston Churchill received his commission in the Oxfordshire Hussars as a captain on 3 January 1902. He took command of the Henley squadron and participated in his first drill meeting the same day.2 He was active in the squadron for many years and was promoted to major on 25 May 1905. This rank he maintained for the balance of his yeomanry service, which continued until 6 August 1924. Churchill remained in command of his squadron until the beginning of the First World War, when his cabinet duties took over his schedule. Later during the war, he commanded the 6th battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers on the Western Front in the early months of 1916.3

Permanent Duty

The four squadrons of the Oxfordshire Yeomanry trained separately for most of the year except for the annual summer training encampment, called “permanent duty,” when they trained together. These were held at one of the large estates in Oxfordshire. During the period of Churchill’s service with the regiment before the Great War, the Q.O.O.H. summer exercises were most often held at Blenheim, with the main camp located in the great park north of the palace. Their tents were set up around the 127-foottall Column of Victory, which is topped by a larger-than-life statue of the first Duke of Malborough, the victor of the Battle of Blenheim.

The grounds of the estate offered more than adequate space for the men’s tentage and for the picketing of the hundreds of horses, as well as cavalry drills “at the trot or gallop.” There was plenty of water in the lake for the mounts, and plenty of hospitality in the palace for the officers and the families who often accompanied them.

The 1911 permanent duty may serve as an example of this splendid annual event. It was hosted by Churchill’s cousin the ninth duke, who also commanded the regiment. That year the program ran from 25 May to 6 June.4 The encampment had a busy daily schedule with reveille at 5:30 a.m., last post at 11:15 p.m., and lights out at 11:30 p.m.5 Time was given over to parades, a full day of drill, caring for the horses, and inspections. There was also time set aside for full-dress parade formations in the courtyard of the palace and Sunday church parades.

The program was not just for serious training. When all four squadrons were together, there could be a regimental reunion. After the work schedule ended at 6:30 p.m., there was time for social gatherings, picnics, and balls that were popular with the soldiers and their families.

Consuelo Vanderbilt, first wife of the ninth duke, wrote in her memoir that the permanent duty days at Blenheim “under canvas were a gay time with dinners and dances and sports. I remember an exciting paper chase which I won on a bay mare, thundering over the stone bridge in a dead heat with the adjutant.”6

Major Churchill enjoyed the exercises in 1911 and wrote to Clementine on 2 June: “The weather is gorgeous and the whole park in gala glories. I have been out drilling all morning and my poor face is already a sufferer for the sun. The air however is deliciously cool. We have 3 regiments here, two just outside the ornamental gardens and a third over by Bladon. I have 104 men in the squadron.”7

The public was invited to attend certain events and there were often big crowds present to watch the march past on the last day of the permanent duty. The march past in 1911 was especially grand, as it was a full brigade affair. Writing again to his wife on 5 June Churchill described the march past that day:

We all marched past this morning—walk, trot & gallop. Jack & I took our squadrons at the real pace and excited the spontaneous plaudits of the crowd. The Berkshires cd not keep up & grumbled. After the march past I made the General form the whole Brigade into Brigade Mass and gallop 1,200 strong the whole length of the park in one solid square of men & horses. It went awfully well. He was delighted.8

Although Churchill was serious about the business of military training, he clearly enjoyed the dash and pomp of the cavalry, which was soon to vanish from the scene. He never lost his fond memories of cavalry drill. In My Early Life he wrote:

There is a thrill and a charm of its own in the glittering jingle of a cavalry squadron manoeuvring at the trot; and this deepens into joyous excitement when the same evolutions are performed at a gallop. The stir of the horses, the clank of their equipment, the thrill of motion, the tossing plumes, the sense of incorporation in a living machine, the suave dignity of the uniform, all combine to make cavalry drill a fine thing in itself.9

The Last Post

Churchill’s ties to the Q.O.O.H. did not end with his retirement from it in 1924. He was appointed Honorary Colonel of the regiment in 1953 and held that position for many years. His attachment to both his yeomanry regiment and Blenheim did not even end with his death in January 1965.

A detachment of three officers and twenty-one men from the successor unit to the Queen’s Own Oxfordshire Hussars, 5 (QOOH) Squadron of the 39th Royal Signals Regiment, under the command of Major Timothy L. May, had the honor of marching in Churchill’s state funeral from Westminster Hall to St. Paul’s Cathedral.10 This was a fitting farewell from the men of the Oxfordshire Yeomanry with which Churchill had served for two decades. After the service, Churchill’s body was laid to rest in the churchyard of St. Martin’s, Bladon, within sight of Blenheim Palace and quite near the site of his regiment’s summer training ground.

Churchill’s Territorial Decoration, awarded in 1924 for twenty years of meritorious service with the regiment, and an example of the full-dress uniform of the Q.O.O.H. are on display in the Churchill War Rooms Museum in London. One should also not miss the Soldiers of Oxfordshire Museum in Woodstock, close by the gate to the Blenheim Palace grounds. It has a splendid collection of military displays, documents, photographs, uniforms, and militaria, including items relating to Churchill’s service in the Q.O.O.H.

Endnotes:

1. Walter Richards, His Majesty’s Territorial Army, vol. I (London: Virtue, 1909), p. 182.

2. The London Gazette, War Office, 3 January 1902, p. 10.

3. The London Gazette, War Office, 30 May 1905, p. 3866, and 5 August 1924, p. 5891.

4. Holdings of The Oxford Yeomanry Trust, Henley Album, F 99 and F 100.

5. Holdings of The Oxford Yeomanry Trust, Henley Album 2, F 36.

6. Consuelo Vanderbilt Balsan, The Glitter and the Gold: An Autobiography (New York: Harper, 1952), p. 84.

7. Randolph S. Churchill, ed., The Churchill Documents, vol. II, 1896–1900 (Hillsdale: Hillsdale College Press, 2006), page 1087.

8. Ibid, p. 1089.

9. Winston S. Churchill, My Early Life (London: Thornton Butterworth, 1930), p. 78.

10. Author’s interview with Timothy L. May, 18 May 2004.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.