Finest Hour 186

Making a Breakthrough

March 11, 2020

Finest Hour 186, Fourth Quarter 2019

Page 14

By Edwina Sandys

Edwina Sandys is an award-winning artist based in New York City. Her books include Winston Churchill: A Passion for Painting (2015).

“May we dedicate ourselves to hastening the day when all God’s children live in a world without walls, that would be the greatest empire of all.”

President Ronald Reagan, 9 November 1990,

Fulton, Missouri

Thirty years ago on 9 November 1989 along with the rest of the world, I was glued to the television screen, watching the Berlin Wall crumble and fall. The souvenir hunters immediately started chipping away. It was, however, only when I learned that the East Germans had removed long stretches of the Wall intact and were selling them that an idea came to me.

2024 International Churchill Conference

“Wouldn’t it be wonderful,” I thought, “to get a piece of the wall, make a sculpture out of it, and then place it at Westminster College?” This would forever link the Berlin Wall with my grandfather Winston Churchill’s “Iron Curtain” speech made at the college in Fulton, Missouri in 1946 and in which he famously said:

From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent. Behind that line lie all the capitals of the ancient states of Central and Eastern Europe…in what I must call the Soviet sphere, and all are subject…not only to Soviet influence, but to a very high and in some cases increasing measure of control from Moscow.

No sooner thought than done, my husband, architect Richard Kaplan, and I were on the next plane to Berlin. Through introductions by my friend at the UN, Hans Janitscheck, we were able to meet with members of what was still then the Communist government of East Germany, men who were already adopting capitalistic ways: they were charging up to $200,000 for each 12’ by 4’ wide section of the wall.

Explaining our mission to the Minister of Culture, who was in charge of the wall, was easier than expected. They had heard of Fulton and of my grandfather, and they knew the “Iron Curtain” speech word for word.

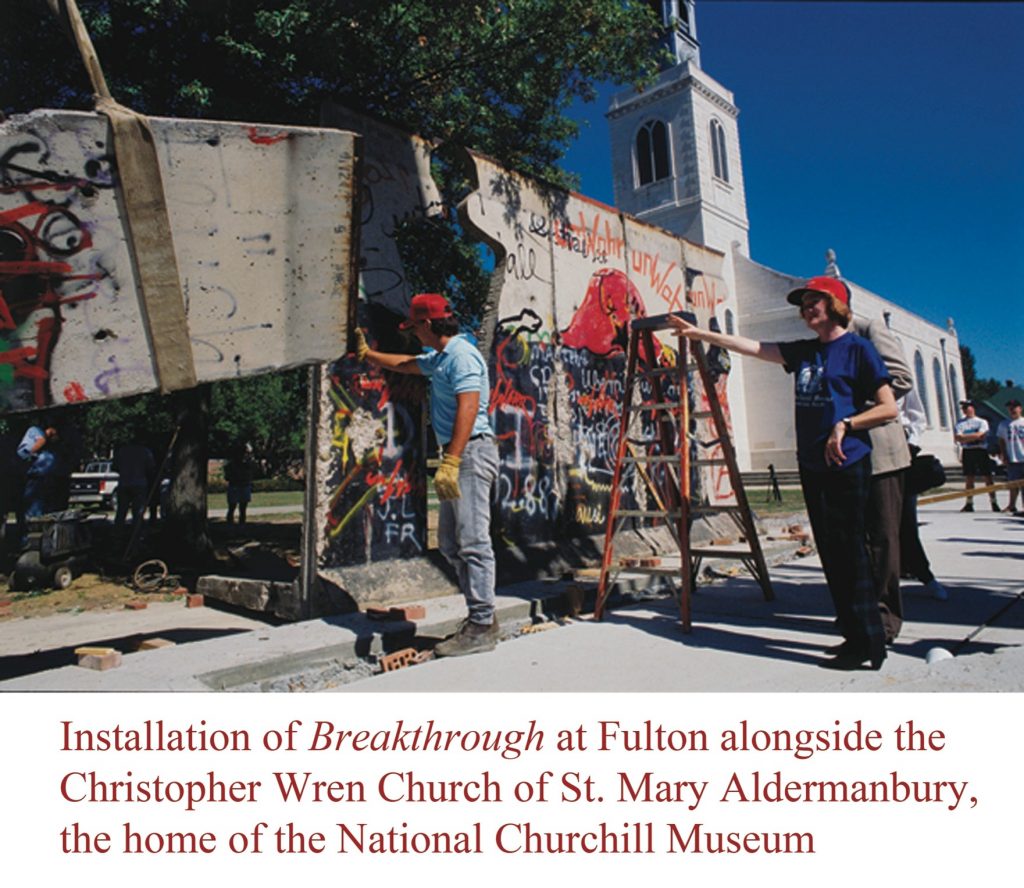

The sculpture was to stand beside St. Mary, Aldermanbury, the Christopher Wren church, bombed in London during the Blitz in December 1940. The church was brought stone by stone from London and set up on the campus as a memorial to grandpapa’s famous speech.

It was a strange feeling, after so many years of the Cold War, sitting down together and working on a joint project with people I grew up to regard as “the enemy.” The East Germans were human, they were friendly, they were enthusiastic. The idea of placing a monument to the demise of the Berlin Wall near the statue of Churchill in Fulton appealed to them. I thought I would need six sections but Richard said I should ask for eight in case I made a mistake. The East Germans had hoped to sell the pieces at full price but agreed to give them all to me—eight sections— free of charge. YIPPEEEE!

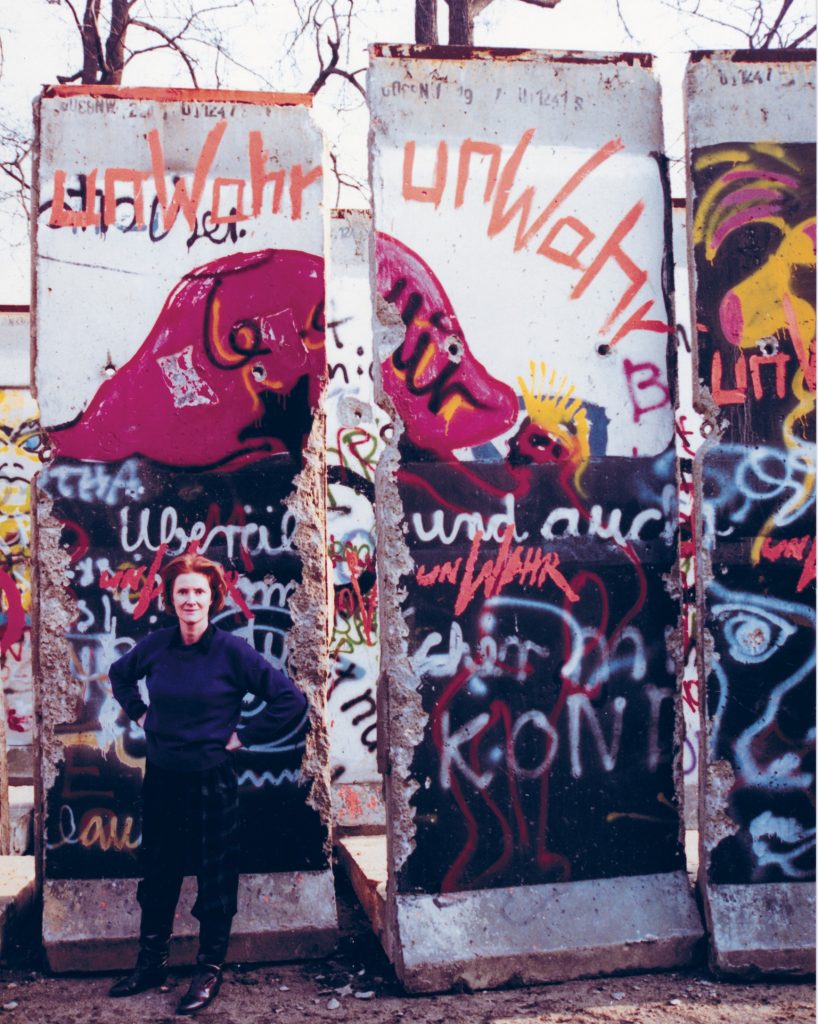

Without more ado, Richard and I went off to the large yard where several hundred of the better-looking sections of the wall were set up row upon row. I chose the sections I did because the colors of the graffiti on the West Berlin side were dynamic and lovely. I was also struck by the repetition of the word “UNWAHR,” which means “LIES” or “UNTRUTH.”

Weighing sixteen tons altogether, the blocks were all shipped from Hamburg to the United States where they were hauled to a warehouse, which served as a studio, in the Long Island City neighborhood of New York.

That was the end of the beginning.

For most of the major sculptures I had made in the past, I have used “noble” materials—marble and bronze. Thirty-two feet of concrete presented quite a challenge.

But what more truly noble material could there be than these ungainly slabs steeped, as they were, in heroism and history? On the colorful West Berlin side, what hopes and fears have been expressed? On the grey East Berlin side, where no one could get near to write or paint anything, what dreams go unrecorded? With great trepidation, and a lot of planning and skill, this precious material was cut by a high-powered water jet.

I wanted to portray FREEDOM—but how to turn a piece of concrete into an abstract idea? The Wall represents UNFREEDOM. Two spaces were cut through, one shaped like a man and one like a woman, each representing FREEDOM. I called it BREAKTHROUGH or DURCHBROCH in German.

Through these two openings people can pass freely, as it were, from East to West, or from West to East. They can imagine what it must have been like to be on the other side—especially the East side where the Wall held people in. Nowadays, people walking through the sculpture people can make their own BREAKTHROUGH. They can use it for meditation, as they might walk a labyrinth—to make a wish, to make a resolve.

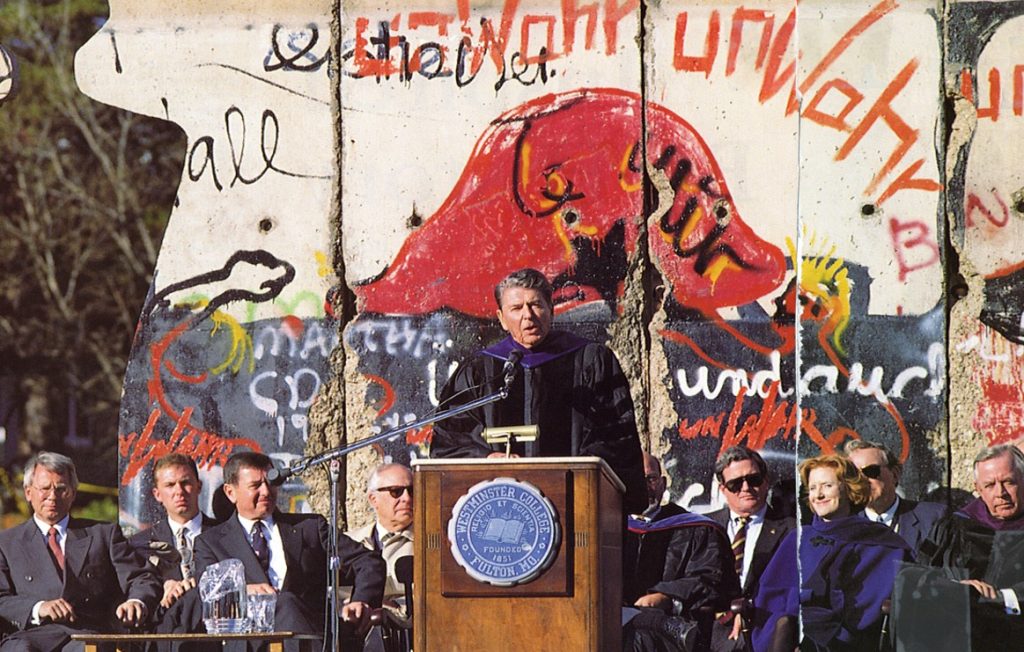

Dedication

BREAKTHROUGH was dedicated in 1990 by President Ronald Reagan—one year exactly after the fall of the Berlin Wall. As President in 1987, Reagan had famously demanded: “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” Three years on, as he spoke in Fulton, Reagan said with a happy smile: “Today we come full circle from those anxious times. Ours is a more peaceful planet because of men like Churchill and Truman and countless others who shared their dream of a world where no one wields a sword and no one drags a chain.”

President Reagan closed his speech that day with these inspiring words: “Here is one spot on earth where we have the brotherhood of man made up of people representing every corner of the earth, maybe one day boundaries all over the earth will disappear as people cross boundaries and find out that, yes, there is a brotherhood of man in every corner.”

Eighteen months after President Reagan’s visit, Mikhail Gorbachev came to Fulton with his wife and daughter on 6 May 1992. The Westminster College campus was filled with a joyous crowd on this uplifting occasion. Gorbachev’s speech was entitled “The River of Time,” and he spoke from the same lectern my grandfather had used five decades earlier. The last leader of the Soviet Union proclaimed that humanity had entered a new era of history, and acknowledged the ills of the Cold War:

Here we stand, before a sculpture in which the sculptor’s imagination and fantasy, convey the drama of the “Cold War,” the irrepressible human striving to penetrate the barriers of alienation and confrontation. It is symbolic that this artist, Edwina Sandys, was the granddaughter of Winston Churchill and that this sculpture should be in Fulton.

That was a hopeful time, right after the fall of the Berlin Wall. The Cold War was over—relations between East and West got warmer. But the ending is never the ending. History has its own willful way of asserting itself.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.