Bulletin #53 - Nov 2012

Last Volume of Churchill Biography: How His Indomitable Spirit Kept Britain’s Hopes Alive in War’s Darkest Days

November 9, 2012

William Manchester’s freind and fan, Paul Reid, finishes the third and final volume of The Last Lion.

By James Andrew Miller

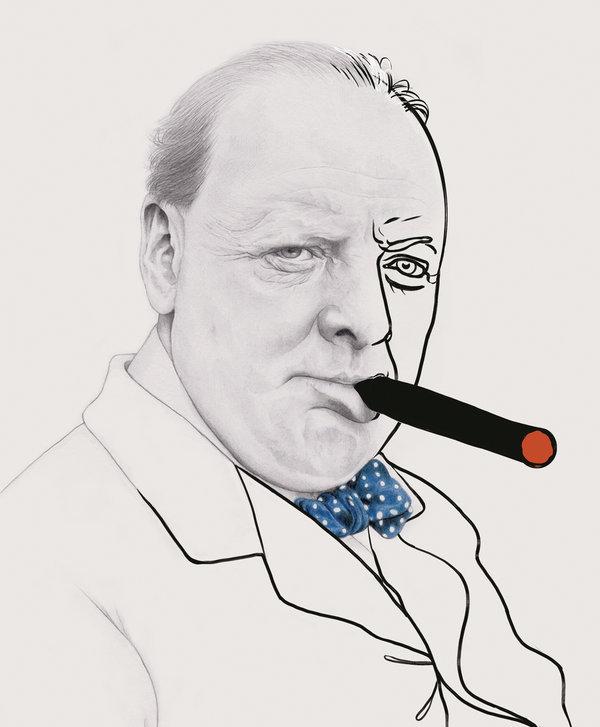

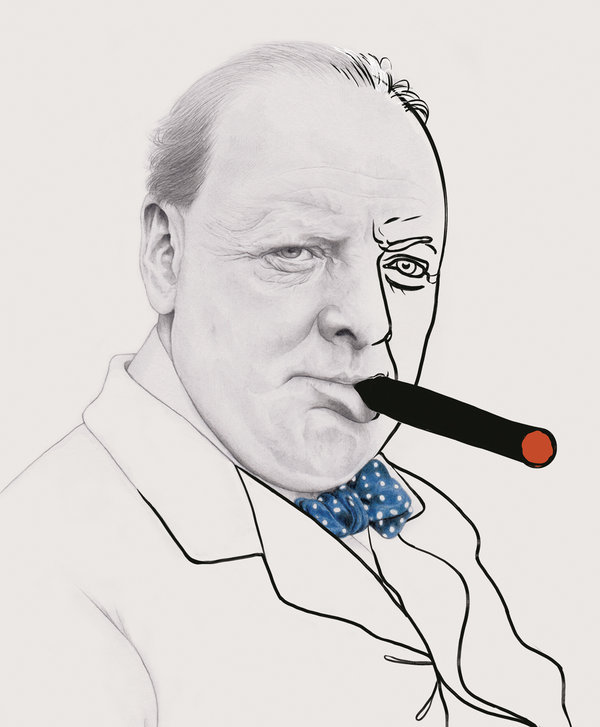

Illustration by Denise Nestor and Shout THE NEW YORK TIMES MAGAZINE, 1 November 2012 — After one of the longest waits in publishing history — more than 20 years — the third and final volume of William Manchester’s biography of Winston Churchill, “The Last Lion,” is finally about to arrive in bookstores. Manchester, who died in 2004, will not be among those eagerly awaiting its reception. The man with the most at stake is the co-author of record, and in fact the actual author: Paul Reid, who had never written a book before and whose specialty before he met Manchester was features for The Palm Beach Post. The story of how Reid, 63, was plucked from anonymity and thrust into the spotlight is not a simple understudy-replaces-star saga, and it’s safe to say that Reid could not have imagined what a mixed blessing he would experience after accepting Manchester’s invitation to co-write the third volume of Churchill’s biography. Now he has emerged from the project in a kind of literary shell shock, knowing that if the book is a success, most of the praise will go to Manchester, and if it flops, blame will fall on him.

Illustration by Denise Nestor and Shout THE NEW YORK TIMES MAGAZINE, 1 November 2012 — After one of the longest waits in publishing history — more than 20 years — the third and final volume of William Manchester’s biography of Winston Churchill, “The Last Lion,” is finally about to arrive in bookstores. Manchester, who died in 2004, will not be among those eagerly awaiting its reception. The man with the most at stake is the co-author of record, and in fact the actual author: Paul Reid, who had never written a book before and whose specialty before he met Manchester was features for The Palm Beach Post. The story of how Reid, 63, was plucked from anonymity and thrust into the spotlight is not a simple understudy-replaces-star saga, and it’s safe to say that Reid could not have imagined what a mixed blessing he would experience after accepting Manchester’s invitation to co-write the third volume of Churchill’s biography. Now he has emerged from the project in a kind of literary shell shock, knowing that if the book is a success, most of the praise will go to Manchester, and if it flops, blame will fall on him.

Enlarge This Image

Manchester would have been a hard act to follow for even a much more seasoned writer. Back in the late 1970s, he began his biography of Churchill for what would end up being a $1 million advance. Then a writer in residence at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Conn., Manchester was the author of more than a dozen major works, including “The Death of a President,” the landmark 1967 study of John F. Kennedy’s assassination, and biographies of Gen. Douglas MacArthur (“American Caesar”) and H. L. Mencken (“Disturber of the Peace”). He was also an outsize personality, known for writing sessions that lasted as long as 50 hours and for turning out books at a metronomic clip.

2024 International Churchill Conference

Each Churchill volume took Manchester four years to write, but the second was much more difficult for him. Unknown to Manchester’s friends, admirers and, perhaps most important, his publisher, Little, Brown & Company, he had begun to struggle with writer’s block. For years, it had been what he feared most, telling at least one intimate, “I’ve been lucky so far.” Then, in March 1985, Manchester confessed in a note his son found among his papers: “For the first time in my life, I have a writer’s block. It is a real crisis. In the past three weeks, I have written exactly four pages. It is very painful.”

Except for reactions from some academic critics, the first two volumes of “Last Lion” were widely praised by reviewers and embraced by the public. But the second volume, published in 1988, took readers only as far as 1940. A third volume would be needed. Manchester struggled. It took him several years to write just 100 rough pages. He was so distraught by his lack of progress on the complicated book that he took an abrupt break to write “A World Lit Only by Fire,” a short work on the medieval era and the Renaissance. It was enough to maintain the illusion of his continued productivity. But no sooner had he completed it than he relapsed into a state of creative inertness.

Among both his editors at Little, Brown and Manchester’s own circle of friends and associates, concern grew about his work on the Churchill biography. Yet even the gentlest of suggestions that Manchester could use help from another writer brought a quick, stern no. Then in 1998, after 50 years of marriage, his wife, Julia, died. About a month later, he suffered a stroke, followed by another soon after. He whiled away days playing with his cocker spaniel, following his beloved Boston Red Sox or, least productively, drinking whiskey. None of it helped. Physically as well as psychologically unable to write, Manchester had to take the step he would have found unthinkable earlier in his career — pick another writer to help him finish “The Last Lion.”

Manchester and his publisher discussed possible collaborators — among them, Russell Baker, Evan Thomas, Robert MacNeil, Walter Isaacson and Carlo D’Este. Baker politely declined, and Manchester rejected the rest. Many historians volunteered, but Manchester was adamantly opposed to hiring a professional historian. He wanted “a writer.”

Look for The Churchill Centre’s review of The Last Lion to be published in an upcoming Finest Hour.

When his publisher suggested Diane McWhorter, the highly praised author of “Carry Me Home,” an account of the 1963 bombings in her native Birmingham, Ala., Manchester finally relented. Told that she was among those being considered for completing Manchester’s Churchill book, McWhorter made it clear she did not wish to be involved in a literary “bake-off” and expressed major doubts about completing another author’s work. Executives at Little, Brown assured her that she would not be party to some undignified game-show situation nor would she be asked to write faux-Manchester prose. She agreed to submit sample pages for consideration.

Supplied with research by the publisher, McWhorter spent the next six months working on what she refers to as a “well-paid audition” — 25 pages on the German bombing of London during the blitz early in World War II. Her pages, submitted in March 2002, were well received at Little, Brown. Manchester even called McWhorter for what she says was a “great conversation” that began with his quoting to her the opening line of “Gone With the Wind”: “Scarlett O’Hara was not beautiful, but men seldom realized it when caught by her charm.” McWhorter also recalls Manchester’s having been “very candid about how diminished he was” mentally and physically.

A month later, “Carry Me Home” won a Pulitzer Prize. Manchester called to congratulate McWhorter. He joked that the cover of the third Churchill volume would have her name in big letters and his “in much smaller ones.” And yet Manchester still would not close the deal with her. Instead, according to McWhorter, Manchester, fearing she held Churchill in insufficient awe, decided she should write another 15 pages. That was it: McWhorter put an end to the auditioning.

In 1996, The Palm Beach Post assigned Paul Reid to cover the reunion of a group of veteran Marines from World War II that included William Manchester. Although Manchester was too ill to attend, Reid got along so well with the other Marines that in 1998 they invited him to join them on a trip to Manchester’s home in Middletown. Reid and Manchester bonded over their mutual love of military history and eventually became such close friends that Manchester revealed to Reid the trouble he was having finishing his Churchill biography.

Reid regularly traveled from Florida to visit Manchester in his home, always trying to raise his new friend’s sagging spirits. During one visit, on Oct. 9, 2003, the two men sat in Manchester’s bedroom drinking — whiskey in Manchester’s case, red wine in Reid’s — snacking on popcorn and watching the Boston Red Sox try to upset the New York Yankees for the American League pennant. Reid says he noticed Elmore Leonard’s novel “Maximum Bob” on the bed. After the game, Manchester asked Reid to retrieve a large suitcase from his study. It was a big room, more than 16 feet long, with an oversize desk taking up most of one wall; Yousuf Karsh’s famous photograph of Churchill and a picture of Jacqueline and John F. Kennedy autographed for Manchester by the first lady were on display. What Reid noticed most of all, though, were the empty wastebaskets, the still-sharp, unused pencils, the uncluttered desktop. The room was more like a museum exhibit than a working office.

In Reid’s telling, he brought the suitcase to Manchester, who had another whiskey and told him to have a seat. “I’d like you to finish the book,” he said. At first, Reid thought Manchester meant he wanted him to read aloud from “Maximum Bob,” much as Manchester himself had read “Huckleberry Finn” to an ailing, elderly Mencken years before.

But Manchester’s meaning became clear after he opened the suitcase. It contained pages and pages of research materials, the raw ingredients for the third volume of the Churchill biography. Manchester admitted that he could never finish the work by himself. “You’ll write, I’ll edit,” he told Reid. Then he said, “We’ll be partners, 50-50 down the line.” Reid would be the co-author, receive equal (though not top, it would turn out) billing on the cover and, Manchester said — making a tomahawk-chopping motion with his right hand — get half of all royalties generated by the third volume.

“Before that moment, I never imagined that would happen,” Reid says. After his own audition — a treatment of the blitz that was considered fine at Little, Brown — Reid was approved by the publisher. Clearly, the company was reluctant to argue with Manchester’s choice. Manchester’s agent, Don Congdon, quickly negotiated an advance for Reid of roughly $200,000. Everyone, including Reid, thought the book would take about two years to complete. After all, Manchester had given Reid his precious “clumps,” the modular results of years of research, both original and secondary.

On June 1, 2004, five months after receiving a diagnosis of stomach cancer and eight months after forming his partnership with Reid, Manchester died. Reid was on his own. It was at this point that executives at Little, Brown made perhaps their most important decision in terms of the book’s survival: They turned to Bill Phillips, a former editor in chief at Little, Brown, to help Reid finish the book. Phillips had not worked on the first two volumes, but his résumé included having edited works by Nelson Mandela, Malcolm Gladwell, Steve Martin and Herman Wouk, among many others. (As a young assistant in the marketing department, Phillips traveled with Manchester on book tours to Chicago and Washington in 1968.) Phillips shared Reid’s assumption that the project would not take long.

But there were problems right away. Manchester’s “clumps” were, in fact, so idiosyncratic that Reid found them more confusing than edifying. Had Manchester been able to work as he did on the first volume, Reid says, “he could have finished the book in a couple of years, but I couldn’t use a lot of what would have worked for him.” It would take Reid two years before he could fully decipher Manchester’s coding system. Frustrated, Reid began his own studies of Churchill and the war.

“Paul had to do it his way,” Phillips says. “There was no other choice but to reinvent the wheel.”

Phillips nonetheless found some of Reid’s techniques confusing. “Paul would write different sections — he called them ‘quilts’ — and sort of jumped around a lot, coming back repeatedly to each little piece, revising it, and then assembling enough to start stitching the thing together,” Phillips says.

In an e-mail to a colleague at Little, Brown, Phillips wrote: “Paul has little conception of what editing means. He tends to get fixated on what are copy-editing issues, although I repeatedly tell him to leave it alone for the time being and pretend he’s Patton, racing through to the end, leaving the task of picking up discarded gasoline cans for the end of the war.”

Despite pressure from the outside world — every month the publisher was getting inquiries from interested readers, including one man who said he had Stage 4 cancer and only a year to live and wanted to know if he would get to read any pages — Reid refused to be rushed. “Everybody had to understand it was going to get done when it got done,” he says. “I went where the facts took me.”

Anxiety ran high. “I have endless e-mails from Paul saying things like, ‘Two weeks from now, you’ll get the final part of Part 1, 30,000 words,’ ” Phillips says. “I realized that having never written a book before, Paul had no idea how much time it was really going to take, and so his estimates were, as he would cheerfully admit later, hopelessly off,” he says. “And some of what did come in was really rough.”

Reid initially tried writing in Manchester’s grandiose voice before Phillips insisted that he stop. “It was impossible for Paul to emulate Manchester’s style,” Phillips says. Long, dramatic Manchesterian sentences were jettisoned. Phillips told Reid to stop calling his subject “Winston,” even though that would have been consistent with the first two books. Phillips also reproached Reid for overindulging in metaphors: “Your prose is like a cloudless day, with fish jumping, and sailboats sailing and the wind at your back.” On one occasion, Reid told him, “I’ve been seeing a metaphor therapist for months now (she does cliché and simile therapy as well).”

Storytelling was Reid’s biggest challenge. “Here’s a guy who never did anything as complicated as this in his life,” Phillips says, “and the gazillion things happening at every moment were tough to manage. Just take 1940. How do you move from a discussion of aircraft production to what was going on in the Churchill family to issues about F.D.R., the Battle of Britain and where the Germans were going to invade?”

Phillips would end up giving the overwhelmed first-timer a six-year course in book writing.

“I never lost confidence that we would get there eventually,” Phillips says, “partly because I’ve been in that position a number of times with different authors. It also has to do with my arrogance, if you want to call it that, in that I always felt capable of guiding any troubled project to fruition.”

With time, Reid gained confidence. He charted his own course, for instance, on two major historical controversies: Churchill’s mental state and his relationship to alcohol.

After studying Mayo Clinic mental-health protocols and consulting other experts about Churchill’s probable state of mind, Reid came to a conclusion at odds with Manchester’s opinion that Churchill suffered from mental illness. He just lived in stressful and depressing times. “I don’t know why Manchester imparted that dark side to Churchill,” he says. “Every writer puts some of himself into his story. My take on the issue of depression is vastly different than Bill’s was.”

On the subject of drinking, Manchester had concluded that Churchill poured one weak drink at the start of each workday and nursed it for hours. Reid’s research led him to believe that Churchill helped himself quite liberally to the bottle — especially when working at night — and simply did a masterly job of handling the alcohol.

Although Reid and Phillips sent small sections of the manuscript back and forth an uncounted number of times, they never exchanged the manuscript as a whole. Throughout the process, they communicated only over the phone and in e-mails (more than a thousand between 2007 to 2011). To this day, Reid and Phillips have never met in person.

The third volume of “The Last Lion,” subtitled “Defender of the Realm, 1940-1965,” turned out to be more of a stand-alone book than a continuation of the first and second volumes. It is an exhaustively researched and detailed account of Churchill’s life during World War II. Kirkus called it “essential for Manchester collectors, W. W.II buffs and Churchill completists.” Publishers Weekly declared it “worth the wait,” writing that “Manchester (and Reid) matches the outstanding quality of biographers such as Robert Caro and Edmund Morris.”

In the author’s note, Reid thanks many friends, several of whom lent him money while he was working on the book. The advance barely saw him through the first two years of what became a difficult seven-year period in which he sold his house, gave up his health insurance and emptied his and his wife’s 401(k) and I.R.A. accounts. Nearly as painful, he says, is that after 30 years of never carrying a balance, he eventually had to live off credit cards. He has never totaled up the debt. “I don’t want to see the investment my family has in this,” he says.

About the last nine years of his life, Reid is direct. “It was very simple,” he says. “Manchester was dead. If I wasn’t going to do it, it wasn’t going to get done.” But when asked if, in hindsight, he would accept the job all over again, Reid shakes his head. “There was a lot that I didn’t know,” he says. “I could never have imagined that it would be so difficult, take so long or have the impact that it had on me and my family.”

But then he reconsiders. “When the galleys arrived, my wife and I took them out of the box, and” — he pauses and tears up before going on. “It was very powerful. When I signed a copy of the galleys for my son, it was one of the best moments of my life. On that day, the sacrifice was worth it.”

Please visit The New York Times website to read more.

©The New York Times. All rights reserved.

James Andrew Miller is co-author of Those Guys Have All the Fun: Inside the World of ESPN. Editor: Dean Robinson.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.